Auction Design for the Private Provision of Public Goods in

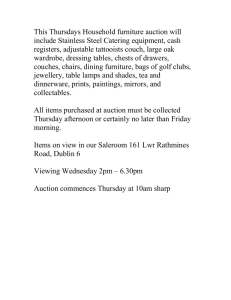

advertisement

World Development Vol. xx, No. x, pp. xxx–xxx, 2012 ! 2011 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. 0305-750X/$ - see front matter www.elsevier.com/locate/worlddev doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2011.12.007 Auction Design for the Private Provision of Public Goods in Developing Countries: Lessons from Payments for Environmental Services in Malawi and Indonesia OLUYEDE C. AJAYI ICRAF Southern Africa, Lilongwe, Malawi B. KELSEY JACK Tufts University, MA, USA and BERIA LEIMONA * ICRAF Southeast Asia, Bogor, Indonesia Summary. — Payments for environmental services programs use direct incentives to improve the environmental impacts of private land use decisions. An auction offers an approach to efficiently allocating contracts among least-cost landholders, which can improve the overall cost-effectiveness of the approach. However, experiences with auctions in developing country settings are limited. We compare the results of two case studies that use auctions to allocate payments for environmental service contracts in Indonesia and Malawi. While the settings and the contracts differ, regularities in auction design allow comparisons and general lessons about the application of auctions to payments for environmental services programs. ! 2011 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. Key words — payments for environmental services, cost-effectiveness, auction, land use, Malawi, Indonesia 1. INTRODUCTION ative to alternative allocation approaches, though potentially at higher prices. Both cases used a budget constrained pricing approach in the auction, which resulted in around 40% of bidders receiving contracts. Imperfect contract implementation in both cases is consistent with variable opportunity costs of implementation. Finally, the distributional implications of the program implementation in both cases suggest some correlation between socioeconomic status and contract allocation, favoring better-off landholders in Indonesia and worse-off landholders in Malawi. Whether the contract actually serves to improve livelihoods remains an open question. In the next section, we discuss the current trend of payments for environmental services in the developing world. Section 3 Payments for environmental services (PES) offer a theoretically elegant approach to resolving the externalities that flow from private land use decisions. The apparent logic of using direct incentives to achieve environmental and conservation objectives has contributed to the increasing popularity of PES and similar initiatives. In developing countries in particular, the number of PES programs and projects continues to grow. 1 Careful attention to program design, combined with rigorous testing at the pilot stage, can help ensure that the PES approach meets its potential and does so cost effectively. In particular, the design and implementation of PES programs are susceptible to information asymmetries between the implementing organization or the buyers of environmental services and the service providers. If some landholders can deliver the service more cheaply, then targeting them for inclusion in the program will lower overall program costs (Ferraro, 2008). 2 This paper describes the implementation of two auctions used to allocate environmental service contracts to the lowest cost landholders. To our knowledge, these are among the first PES auctions implemented in developing country settings. We compare the auction designs and their outcomes, and discuss potential policy lessons. Though the settings in which these two cases were implemented differ on several dimensions, similarities in auction design allow us to make comparisons and identify common lessons regarding PES auction design in developing countries. To briefly summarize our findings, we show evidence consistent with more cost effective allocation under the auctions rel- * The authors gratefully acknowledge financial assistance provided by the European Union to ICRAF under the auspices of the “Environmental Governance Project in Africa” and, the Irish Aid through their support to the “Agroforestry Food Security Project.” Funding was also provided by the International Fund for Agriculture and Development (IFAD) and the Economy and Environment Programme for Southeast Asia (EEPSEA). Jack received research support from the Sustainability Science Program at Harvard University and the Weatherhead Center for International Affairs. We are grateful to Festus Akinnifesi, Meine van Noordwijk, Brent Swallow, William Clark, and Christopher Avery for support and advice, Stanley Mvula, and Rachman Pasha for assistance in the field, and the farmers who collaborated with us throughout the study. The study does not represent the official view of the organizations and individuals mentioned above. Any errors or omissions contained herein are the authors’ responsibility only. Final revision accepted: November 11, 2011. 1 Please cite this article in press as: Ajayi, O.C. et al. Auction Design for the Private Provision of Public Goods in Developing Countries: Lessons from Payments for Environmental Services in Malawi and Indonesia, World Development (2012), doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2011.12.007 2 WORLD DEVELOPMENT describes how auctions resolve the information asymmetry in contract allocation, and Section 4 discusses the particular challenges presented by developing country implementation. We present the two case studies in Section 5, first discussing the Indonesia case then showing a similar set of analyses for Malawi. In Section 6, we provide a comparison of the results. Finally, we conclude with policy lessons and areas for future research. 2. PAYMENTS FOR ENVIRONMENTAL SERVICES AND ASYMMETRIC INFORMATION (a) Agricultural externalities and environmental services Environmental services from agricultural land represent a classic externality problem, in which private actors will not act in society’s best interest if the costs or benefits of their actions are shared with others. In his seminal articles on the structure of the externality problem, Coase (1959, 1960) referenced environmental externalities, including stream contamination. In most cases, environmental externalities from agriculture are not priced, and by maximizing his or her own income from agricultural land, a farmer may generate negative externalities. Putting a price on the externality, through either a tax on pesticide use or a subsidy on abatement, will reduce the production of negative externalities and improve social welfare as long as the marginal cost of abatement is lower than the marginal social benefits from abatement. While either a tax or a subsidy can be used to generate the desired behavior change, the choice between these options has distributional implications. An optimal payment for environmental service provision will, therefore, align the landholder’s private benefit from undertaking land use practices that produce the externality with the social benefits from that externality. 3 While resolving agricultural externalities and increasing environmental service provision by changing prices poses a straightforward solution in theory, it can be extremely difficult to design a feasible policy or program to implement such an approach. A number of articles summarize the challenges associated with design and implementation of PES programs in developing countries (Bulte, Lipper, Stringer, & Zilberman, 2008; Jack, Kousky, & Sims, 2008; Leimona, Joshi, & van Noordwijk, 2009; Wunder, Engel, & Pagiola, 2008 ). While the literature on PES in developing countries is large and varied, we focus here on the particular challenges associated with the private information held by landholders, and discuss context-dependent equity considerations in Section 4. (b) Who to pay and how much to pay them? PES designers must determine who, among eligible participants, should be selected for compensation or contracting. In a smoothly functioning market, this question is trivial since trading will occur, prices will adjust, and contracts will end up in the hands of those who can provide at least cost (Montgomery, 1972). If, however, transaction costs are substantial because the markets have few participants or because information is scarce, then the initial allocation of contracts is important for determining the efficiency of the program (Stavins, 1995). PES programs in developing countries tend to resemble markets with prohibitively high trading costs (Perrot-Maı̂tre & Davis, 2001). Therefore, targeting the lowest cost service providers requires an approach that reveals private information ex ante. Other authors have discussed the importance of information asymmetries for PES design (Ferraro, 2008; Jack, Leimona, & Ferraro, 2009; Latacz-Lohmann & Schilizzi, 2005). Knowing relative costs of service provision among eligible landholders is necessary for determining which landholders should be enrolled in a program. This information resolves the question of whom to pay, and also how much to pay them. The relevant cost measure for consideration is the land holder’s opportunity cost of participating in the program. Opportunity cost is defined as the difference, in value to the landholder, between the contract and business as usual without the contract. The value includes risk aversion and other preferences. Payments below the participant’s opportunity cost will mean, in many cases, that the environmental service is not provided either because the contract is not taken up or because compliance rates are low. Payments above the opportunity cost mean that more environmental services could have been purchased with the available funds. While setting payments equal to opportunity cost is highly cost effective, paying above opportunity cost may be desirable from a poverty alleviation standpoint. We discuss this and other distributional equity factors in Section 4. The information asymmetries are irrelevant for design under the following four scenarios. First, if all landholders have roughly equal costs of environmental service provision, then determining which landholders to enroll into a program will not improve outcomes. Second, if opportunity cost is highly observable or closely correlated with observable farmer characteristics, then policy makers will be able to predict opportunity costs. Cost flow models are an example of this approach (Antle & Stoorvogel, 2006). Third, if landholders do not know their own opportunity costs, then no information asymmetry exists. If, as is more commonly the case, the opportunity cost of environmental service provision is heterogeneous across landholders, and landholders have better information about these costs than does the policy maker, then a mechanism to reveal that information will improve program performance. Finally, opportunity cost may be highly uncertain because of fluctuations in weather, crop prices, or availability of household labor, making it difficult to predict ex ante. In such a scenario, contracting on expected opportunity costs may lead to low contract compliance. Dynamic contracts that vary the incentive price with the opportunity cost may be more effective at achieving environmental outcomes. 3. AUCTIONS: AN INCENTIVE COMPATIBLE ALLOCATION MECHANISM A number of mechanisms can help overcome information asymmetries by giving participants a direct incentive to tell the truth—referred to as “incentive compatible” mechanisms. Certain types of auctions have this property, in which the best bidding strategy is to bid one’s true value for an object (e.g., Vickrey, 1961). With PES contracts, an auction to allocate contracts creates a temporary market where one otherwise does not exist. The competition created in this environment gives participants an incentive to reveal their private information about the lowest payment that would make them willing to accept an environmental service contract (Ferraro, 2008; Latacz-Lohmann & Schilizzi, 2005). In this type of “reverse auction” or procurement auction, only the lowest bidders receive contracts. 4 The case studies described below use a similar auction to allocate environmental service contracts and to determine the contract price. We present the general design features Please cite this article in press as: Ajayi, O.C. et al. Auction Design for the Private Provision of Public Goods in Developing Countries: Lessons from Payments for Environmental Services in Malawi and Indonesia, World Development (2012), doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2011.12.007 AUCTION DESIGN FOR THE PRIVATE PROVISION OF PUBLIC GOODS and the bidding strategy for the PES auctions here to provide intuition for the incentive compatible nature of the individual bidding decision. Vickrey (1961) described a second price, sealed bid auction as a straightforward mechanism with a dominant bidding strategy of truth-telling. 5 In a reverse procurement set up, the lowest bidder wins but pays the price bid by the second-lowest bidder. This ensures that the bidder can do no better than stating his or her own true valuation. If she bids lower, then she risks winning the auction and getting paid less than the amount she needs to implement the contract. If she bids higher, then she risks losing the auction at a price she would have been willing to accept. The same bidding incentives generalize to an auction with multiple units in which each bidder desires only one of these objects (Vickrey, 1976). We described an auction with a uniform price scoring rule, meaning that all winning bids receive the same price. 6 Such a price rule offers the benefit of setting a price slightly above bidders’ minimum willingness to accept, and providing a buffer for bidding errors or shocks to opportunity cost. A buffer may be desirable if actual implementation costs are uncertain. In an auction for PES contracts, each landholder does her best by bidding the lowest price that would make her willing to accept the environmental service contract. The auction offers the benefit of simultaneously allocating contracts and revealing an efficient clearing price. This price may be determined by either a budget constraint (a fixed available amount of money) or a quantity constraint (a target number of contracts) (Schilizzi & Latacz-Lohmann, 2007). 7 Thus, an auction simultaneously determines who to pay and how much to pay them. 4. AUCTIONS IN DEVELOPING COUNTRIES Piloting auctions to allocate conservation contracts in developing countries can help reveal the true benefits and pitfalls of the approach. The private information revealed by auctions may be particularly important in developing countries, where the markets associated with environmental service contracts may not function well, which exacerbates the information asymmetry between the landholder and the policy maker. Where land, labor and credit markets are imperfect, the prices that these markets reveal are likely to differ from the true “shadow price” felt by the household, making it difficult for policy makers to estimate opportunity costs (De Janvry, Fafchamps, & Sadoulet, 1991). In addition, poorly functioning land markets may create obstacles for the fundamental feasibility of the PES approach. Where private property rights are poorly defined, individuals may not be able to place bids involving land that they do not own. In places where land tenure is insecure, changing land use through any contract with external parties may be illegal and create problems with contract enforcement and payment. While auctions have been used in environmental policy settings in developed countries in a number of cases, their application to developing countries is recent. The effectiveness of auctions for improving PES contract allocation may be affected by several conditions related to participants and context. (a) Understanding the bidding strategy Though auctions are regularly used to trade commodities in developing countries, understanding dominant bidding strategies may be challenging to inexperienced market participants. A substantial body of literature in experimental economics suggests that experience is important for accurate bidding (e.g., 3 List, 2003). Because most PES contract allocations are relatively rare, opportunities for participants to gain experience with a contract auction will be few and far between. In addition, with long-term land use contracts, trading following an auction is likely to be disallowed, putting an additional onus on the accuracy of one-shot bids. While the case studies that we present below do not provide direct evidence on the role of experience or training for auction performance, we are able to show suggestive evidence that participants understood the auctions reasonably well. In particular, the Malawi auction benchmarks bids against acceptance decisions under a simpler “take it or leave it” price offer market (see also Jack, 2010). (b) Information asymmetries For an auction to reveal private information, the bidders must have better information than the auctioneer (the implementing agency) about their true values. In developing countries, landholders may not have private information for two reasons. One, if the contracted land use activity is new or unfamiliar, the implementing agency may actually have better sense of the input requirements of the contract than does the landholder. In such a case, the landholder will not provide a better estimate of their true costs than would an estimate provided by the auctioneer. Two, the determinants of opportunity cost are likely to be highly uncertain. While an auction may successfully sort landholders on their ex ante estimates of opportunity cost, these estimates may not be well correlated with ex post realized opportunity cost. In a setting with highly uncertain opportunity cost, sorting on ex ante estimates does little to improve the efficiency of the allocation. 8 We cannot explicitly test for the importance of ex post shocks to opportunity cost in our settings. However, we can explore the relationship between bids, household characteristics, and compliance rates as tentative investigation into these factors. (c) Power imbalance A common concern about contracts for environmental service provision in developing countries relates to the extreme power imbalance between the contracting parties. Though PES contracts are typically structured to be voluntary, with relatively cheap exit options, contracted landholders may feel pressure to implement the contract whether or not it provides them with a surplus above their implementation costs. Sources of pressure may include expectations of future benefits from the implementing organization, or pressure from within one’s own community. These concerns are not unique to the use of an auction, though in a setting where individuals reveal their own prices through bids, these types of pressure may lead to underbidding and a subsequent failure to exit a contract that is harmful to the landholder. Our tentative evidence from Indonesia and Malawi shows no indication that participants deflated their bids, and contract holders exited at a fairly high rate in Indonesia. These findings are discussed below. (d) Distributional equity The distributional consequences of any policy or program tend to be of particular concern in developing country settings. A number of authors have raised questions over the distributional equity of PES contracting. For example, Zilberman, Lipper, and McCarthy (2008) discuss scenarios under which PES is likely to benefit the poor. Particular concerns are often voiced for auction or other market-like approaches because they reduce the size of the transfer going to the landholder. Please cite this article in press as: Ajayi, O.C. et al. Auction Design for the Private Provision of Public Goods in Developing Countries: Lessons from Payments for Environmental Services in Malawi and Indonesia, World Development (2012), doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2011.12.007 4 WORLD DEVELOPMENT If the program’s sole objective is poverty alleviation, then an auction is unlikely to be the optimal targeting approach. If, however, cost effective conservation is the objective, then auction design decisions can help improve poverty alleviation outcomes while still lowering overall program costs. In particular, if opportunity cost is correlated with wealth and PES contracts improve landholder welfare, then targeting landholders with low opportunity cost may also alleviate poverty. However, without first establishing that PES contracts make landholders better off, evaluation of the distributional impacts of contract allocations are premature. We again provide only tentative evidence on these distributional concerns in our case studies below. 5. CASE STUDIES: INDONESIA AND MALAWI 9 While auctions have potential to generate cost effective allocations of PES contracts, the gains will depend on their actual performance. The two cases presented here represent some of the first examples of implementation of auctions for environmental service contracts in developing country settings. 10 The settings, implementation process and outcomes are described separately, then compared directly in Section 6. The technical details of these case studies have been described elsewhere (Jack, 2010; Jack et al., 2009; Leimona, 2010). The new analyses performed here summarize these two case studies and provide parallel results to facilitate comparisons and identify generalizable lessons. (a) Case study 1: erosion mitigation in Indonesia In upland areas, agricultural practices often generate significant watershed externalities, such as water contamination, siltation of downstream irrigation, or power generation dams. Adoption of agricultural practices, such as terracing or reductions in fertilizer use come at a private cost to the upstream farmer but generate downstream benefits. Incentives for upstream farmers to adopt such practices may therefore be necessary to reduce downstream environmental and economic losses. Where these losses are sufficiently large, downstream parties may have a substantial willingness to pay. Coffee farming areas in Southern Sumatra exemplify the watershed degradation caused by intensive upstream agriculture. In Lampung Province, ICRAF implemented a pilot program to assess the performance of an auction to allocate incentive contracts for investments in erosion mitigation practices. Watershed environmental services present a complication for contract allocation because the benefits associated with enrolling each land parcel in a watershed protection program will depend on its spatial location, slope, and other factors. As described in Engel, Pagiola, and Wunder’s (2008) overview article, PES programs may differentiate payments on the costs of environmental service provision, the benefits associated with those services, or both. Where service benefits are likely to be heterogeneous, such as with watershed services, incorporating benefits into the allocation process may improve the overall social benefits from the contracts (Bulte et al., 2008). The objective of the pilot auction in Sumatra was to test the auction performance and not necessarily to generate the greatest benefits at the lowest cost, therefore, benefit heterogeneities were ignored for the purposes of the pilot. (i) Setting and background data Substantial background research contributed to the auction case study implemented in Sumatra. ICRAF researchers performed a preliminary assessment of the hydrology of the area to identify key locations for downstream siltation. The landholdings in two villages were identified as large contributors to erosion, which interferes with operations of a downstream power generation facility. To identify land use practices acceptable to participating farmers that could mitigate erosion from the coffee farms, ICRAF conducted a number of focus group discussions. Three practices that reduce erosion without affecting coffee production were identified: sedimentation pits, contour ridges, and planting grass strips. Before the full auction was implemented, a number of trials were conducted to inform auction design decisions. The trials and methodology have been described in greater detail by Leimona et al. (2010). The first was conducted with Indonesian university students, involving hypothetical bids for room cleaning contracts. The second was conducted with farmers in Sumatra, in villages similar to the final implementation site, again using hypothetical bids. These two sessions were used to refine instructions, train enumerators, and decide among alternative auction design parameters. Parallel to the hypothetical auction trials, ICRAF staff conducted a baseline survey of all households in the designated environmental service contract villages. Baseline information on participants is useful for research purposes but is unnecessary for the effectiveness of the auction. A total of 82 coffee farmers from the two villages participated in the final auction for environmental services contracts in 2006. (ii) Contract design Based on the focus group discussions and consultation with hydrologists, the contract presented in Table 1 was offered to auction participants. The contract stipulated fixed amounts of the three erosion mitigation practices per area. Participants were able to choose the amount of land to enroll and the contract was scaled to their chosen quantity of land. The land areas contracted ranged from 0.25 to 2 hectares. Payment was divided into three installments, the second two of which were determined by compliance rates. For each of the three erosion mitigation practices, any participant who had not completed half of the requirement by the mid-point of the year received no further payment. All contract recipients were provided with training on implementation of the erosion mitigation practices. (iii) Auction design and bids The auction was implemented using a uniform price rule based on a fixed budget constraint. ICRAF staff explained the auction rules to the participants and gave them the opportunity to bid for seven nonbinding trial rounds before the final binding bidding round. During the preliminary rounds, the budget was used to identify the provisional winners, whose identification numbers were announced. No information regarding prices was announced between rounds to avoid spurious bid affiliation (List & Shogren, 1999). The multiple bidding rounds provided participants a chance to become familiar with the auction procedure and to enhance competition among the relatively small number of bidders. To mitigate the potential for collusion, communication among bidders was discouraged and bidders were seated some distance from one another. Figure 1 shows the bid distribution in 10,000 Rupiah (!1USD = Rp9000). Bids were normalized into per hectare prices and ranked as shown. The mean bid per hectare was 2.64 million Rupiah or about USD 293. The bid distribution was very left-skewed, with a median substantially below the mean at 1.63 million Rupiah or USD 181. Based on the total Please cite this article in press as: Ajayi, O.C. et al. Auction Design for the Private Provision of Public Goods in Developing Countries: Lessons from Payments for Environmental Services in Malawi and Indonesia, World Development (2012), doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2011.12.007 AUCTION DESIGN FOR THE PRIVATE PROVISION OF PUBLIC GOODS 5 Table 1. Contract design, Indonesia Key item in the contract Soil conservation activities Description of the contract item – Sediment pits: 600 per hectare, standard dimensions – Ridging: 50% of plot or 1/2 hectare – Vegetation strips: surrounding pits and ridging 1/3 at inception, 1/3 at mid-point contingent on performance, 1/3 at one year contingent on performance Payment schedule Duration and monitoring – One year with monitoring every three months – Termination if 50% contracted activities not completed by mid-term monitoring date Table 2. Baseline characteristic of auction participants, Indonesia 6 7 Number of participants Number of hectares contracted Distance from plot to road Current soil conservation Slope History with NGO 82 (34 received contracts) 25 Mean: 25.96 Winners: 79%; losers: 66% 46% of participants on slope >25% 82.9% had past experience with ICRAF price 4 5 log bid (10,000 Rp) 8 Cancelation or noncompliance results in ineligibility for second payment installation. Force majeur provision for contract terms in the event of natural disasters. 0 20 40 60 80 bid rank Figure 1. Auction bids in (log) Rupiah, Indonesia. funds available and this bid distribution, the 34 lowest bidders (41.5% of bidders) received contracts at a price of around USD 171 for the one-year contract. (iv) Bid calibration To calibrate whether the bids received in the auction approximated opportunity cost, we collected information on estimated implementation costs from several sources. Because the contracted erosion mitigation activities have no effect on coffee production, the primary cost was expected to be driven by the opportunity cost of labor. The implementation time associated with the contract was estimated using the baseline household survey, focus group respondents, and outside agricultural experts. Using market wage rates, estimates of the contract’s labor costs ranged from 2.03 million Rupiah to 2.70 million Rupiah, which are within the range of the mean bid. However, they are substantially higher than the median bid of 1.63 million Rupiah and 30–74% higher than the eventual contract price. The values are consistent with the auction selecting the lowest cost landholders, though it may also be that estimates based on wage labor tend to inflate costs for the reasons discussed in Section 2(b). (v) Program outcomes Contracts with 34 of the 82 auction participants resulted in approximately 25 hectares or 67 acres of erosion mitigation investments. Baseline characteristics of the auction participants are summarized in Table 2. Many participants were already investing in limited activities related to soil conservation, more among those who received a contract than those who did not. The contract rewarded additional investment only, so the previous soil conservation may have influenced selection through bids but is unlikely to have influenced compliance costs. Land holdings are steep, on average, with slopes of greater than 25% gradient for almost half of participants. Most participants had interacted with ICRAF in the past, which may have affected both bids and available information about soil erosion mitigation practices. Many PES programs attempt to address environmental services while also considering socioeconomic impacts of the program. Using the baseline survey data, we can compare the selection under the auction to sample averages. Table 3 shows that contract recipients under auction are better off than the average landholder in terms of asset holdings (adapted from Jack et al. (2009)), though the difference is not statistically significant. Landholdings and education levels among recipients are both very similar to the sample average. These outcomes potentially suggest some disproportionate enrollment of relatively well off households into the contracts. We discuss the implications of pro-poor targeting in Section 6. The primary program objective is, of course, eventual contract outcomes, and compliance with the erosion mitigation contract determines both the environmental effectiveness of the program and also the actual payments levels. Compliance is measured as whether or not the contract holder met the contract requirements by a specified date at the mid-point and end of the one-year contract. All participants received a third of the total payment upfront, however, subsequent payments depended on implementation. Table 4 shows the contract compliance outcomes. All households but one were fully compliant through the mid-term monitoring. However, at the final monitoring period, compliance rates fell to approximately 56% of households. On average, those who were compliant with the erosion mitigation contract were overcompliant, completing around 133% of the required activities. Of those who defaulted on the contract, compliance rates were still well over half, with around 82% of activities completed. Differences in bids between compliant and noncompliant individuals are not statistically significant, though bids among compliant individuals were lower. Please cite this article in press as: Ajayi, O.C. et al. Auction Design for the Private Provision of Public Goods in Developing Countries: Lessons from Payments for Environmental Services in Malawi and Indonesia, World Development (2012), doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2011.12.007 6 WORLD DEVELOPMENT Table 3. Allocation characteristics, Indonesia Contract recipients Sample average 11,190 0.74 5.8 8,667 0.83 5.7 Asset (USD) Area (hectares) Education (years) Note: Adapted from Jack et al. (2009). Table 4. Contract compliance outcomes, Indonesia N % Households % Activities Mean bid (USD) Noncompliant 15 Compliant 19 44.12 55.88 81.92 132.68 118 113 (b) Case study 2: tree planting in Malawi Tree planting on private land generates a number of public benefits, most prominently carbon sequestration. However, for many tree species, private benefits are limited and landholders will not internalize the public benefits associated with tree planting such as carbon sequestration, soil fertility, and habitat. Emerging carbon markets offer a potential source of funding for incentive payments to encourage tree planting, though validation of carbon sequestration at the level of rigor needed to meet current international standards adds significant transaction costs to program implementation. We continue to focus here on landholder selection into the program, putting issues of financing and transaction costs aside. Land use based carbon sequestration is a likely candidate for selecting landholders based only on opportunity cost, which can be achieved through a simple auction. To the extent that no landholder generates significantly greater environmental benefits than any other landholder for a given activity, then selecting on cost will maximize cost-effectiveness. For example, paying landholders based on surviving trees (or, even more precisely, based on tree diameter) substantially reduces the importance of spatial dimensions of environmental benefits. (i) Setting and background data The site selection process for the tree planting contracts in Malawi considered a number of factors related to the expected opportunity cost of participants. A location in the central region of the country was chosen to balance considerations of land and labor availability. As described by Jack (2010), within the selected district, 27 villages were identified. All landholders with clear land rights and at least 0.5 acres were eligible to participate. These eligibility criteria were based on data collected during a baseline survey of households in the candidate villages. The baseline survey and consultation with forestry experts suggested that the preferred species for the contract would be a timber species with high carbon storage and economic value maturing after many years of growth. The species identified was an endemic white mahogany, Khaya athotheca, which grows well in the study area, but is no longer commonly found. For research purposes, we wished to use a tree type that would not be readily available on local markets to avoid contract holders replacing dead trees with new ones purchased from the market. 11 Using a local species also mitigated the chances of any kind of invasive or problematic impacts on the local ecosystem. A pilot was conducted using similar market mechanisms as the final experiment in order to pre-test the implementation script and logistics. During the pilot, we purchased one-day labor contracts to assist with the construction of a nursery where the seedlings would be stored prior to distribution. The pilot was used to pre-test the instructions and train those who would assist with the final implementation. The pilot was small, with only 25 participants, but incentive compatible, meaning individuals had the same incentives to bid truthfully that they would have in the environmental services auction. The final allocation took place several weeks later and involved 432 individuals from 24 villages. (ii) Contract design A three year tree planting contract was offered to all 432 individuals, approximately half of whom participated in an auction similar to that used in Indonesia. The other half received a “take it or leave it” price offer. The contract over which individuals bid is described in Table 5. All farmers were offered the same contract, with a fixed amount of land for tree planting and a pre-determined number of seedlings. Unlike the Indonesia erosion mitigation contract, farmers could not scale the contract to suit their landholdings or other constraints. While erosion mitigation investments do not disrupt agricultural production, planting trees does. Consequently, a contract of limited size was implemented in Malawi. This contract design also provides a clearer relationship between landholder characteristics and contract implementation outcomes. In this case, ICRAF provided several inputs upfront, to reduce the effect of liquidity constraints on bids and on implementation quality. Specifically, the fixed number of seedlings was distributed to each contract holder at the time of the correct planting season. All farmers, whether or not they had received a contract, were invited to join a series of trainings delivered at appropriate points in the contract cycle. These upfront inputs leveled some underlying differences across participants in terms of information and liquidity, but were of limited value if the landholder did not intend to participate in the contract and keep the trees alive. Unlike the case in Indonesia, no contract payment was provided upfront and all payment installments were contingent on tree survival. Such a payment structure minimized the chances that participants would submit low bids to obtain upfront payments or to retain the option to implement. The initial stage of contract implementation included high fixed costs for clearing the field and planting the trees. Contract holders were given specific instructions on use of a contiguous area for tree planting, which was intended to facilitate monitoring and to maximize survival. However, similar projects Table 5. Contract design, Malawi Tree planting – Clear 1/2 acre of land for tree planting – Prepare field, dig planting pits – Plant 50 trees, weed, water and care for trees Payment Payments per surviving tree after: 6 months, schedule 1 year, 2 years, 3 years Duration and – 3 years with renegotiation option monitoring – Monitoring at each payment period NGO inputs – Seedlings provided upfront – 3 trainings on field preparation, planting and care Force majeur provision for contract terms in the event of natural disasters. Please cite this article in press as: Ajayi, O.C. et al. Auction Design for the Private Provision of Public Goods in Developing Countries: Lessons from Payments for Environmental Services in Malawi and Indonesia, World Development (2012), doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2011.12.007 14 (iv) Bid calibration Like in the Indonesia case, we wished to calibrate the Malawi bids against other estimates of the opportunity cost associated with the contract. To do so, we once again assessed the value of different inputs to the contract implementation (see Jack (2010) for greater detail). Market prices for land, labor and other inputs are used, though the value of these inputs will differ from market prices in settings where associated markets are imperfect. Unlike the erosion mitigation contract in Indonesia, the tree planting contract may have affected agricultural production if trees were planted instead of crops. A household that faces market prices for all inputs and converts their half acre of land from crop production bears an opportunity cost between 107,610 and 418,950 Kwacha over the three years of the contract, driven largely by foregone income from crops. A household with idle land would face a much lower opportunity cost according to these estimates, closer to 20,000 Kwacha. While actual opportunity costs are likely to be below these figures, the mean auction bid falls within this range. The clearing price was again set below these estimated levels, reflecting the challenge associated with determining true opportunity cost from observable data in these settings. Specifically, because land, labor, and other input prices on the market do not reflect the shadow prices faced by individual households, these estimates may be over- or under-estimates. 10 12 7 different rates of supply (38% versus 99% of the groups) between the treatments. 8 price 4 6 log bid (kwacha) AUCTION DESIGN FOR THE PRIVATE PROVISION OF PUBLIC GOODS 0 50 100 150 bid rank 200 250 Figure 2. Auction bids in Kwacha (logs), Malawi. with less strict research objectives could allow landholders more flexibility in implementation, which should lower costs to the landholder since planting trees as wind breaks or to delineate property may increase private benefits. (iii) Auction design and bids The implementation of the auction for tree planting contracts in Malawi used an experimental design to generate greater insight into the bidding and contract compliance results of the auction. Jack (2010) describes the implementation and results in greater detail. Participants were randomly assigned to one of two treatments, the first being a uniform price, sealed bid auction, similar to what was implemented in the Indonesia case study, and the second being a take it or leave it price offer, which was run immediately after the auction and used the auction clearing price as the price offer. Contract content and prices were the same for all contract recipients. The two mechanisms are strategically equivalent, making the posted price offer market a useful counterfactual to the auction. 12 Differences in supply and tree survival across the two mechanisms are informative about the benefits of an auction relative to more commonly used approaches. The Malawi auction following the same pricing and bidding rules as the Indonesia auction, though only a single practice round preceded the final bidding round. The number of participants in the Malawi auction was much greater than the number of bidders in the Indonesia auction. Theoretically, the number of bidders does not affect the dominant bidding strategy in a second price auction. However, in a number of other auction formats, increasing the number of participants decreases bid shading and increases competition. If participants remained unsure of the bidding strategy, a larger number of bidders should help to reduce strategic behavior. Figure 2 shows the distribution of bids in Malawi Kwacha, with the vertical axis in logarithm units. The clearing price is shown, which fell at 12,000 Kwacha or about 80USD (1USD = 150 Kwacha) for the full three years of the contract. Actual payments depend on tree survival rates. About 40% of bidders received a contract at this price (those below the price line in Figure 2). The mean bid was around 58,000 Kwacha with a median bid of 20,000 Kwacha. When individuals in the posted price offer treatment were offered the price of 12,000 Kwacha, 99% accepted it. In the auction treatment, 86 individuals or about 38% of the market received a contract. In Section 5(b)(v) we discuss the implications of the highly (v) Program outcomes Contracts with 176 individuals yielded 8,800 trees planted in Central Malawi. In the posted offer group, a lottery was used to allocate contracts after the high sign up rates overspent the budget. The total number of contracts awarded to individuals in that treatment is similar to the total number awarded under the auction. Baseline characteristics of all participants, and those who received a contract are shown in Table 6. Table 6 also allows for some comparisons of the distributional consequences of the program. Like with Table 3, we can compare socioeconomic indicators for those who received contracts with those who did not. Overall, individuals with a history of interaction with the NGO were slightly more likely to receive a contract through the auction (p < 0.10). Household sizes are larger for contract recipients than nonrecipients (p < 0.10). Households that receive a contract under the auction have more months of food shortage and fewer hectares of land than the sample average. Months of food shortage is a proxy for the well-being of a household in this environment. 13 Table 6. Socioeconomic characteristics, Malawi Contract recipients Number of participants Number of contracts awarded Current tree planting History with NGO Household size Months of food shortage Female headed HH Total acreage Education Auction Posted Offer 228 86 0.52 0.39 4.92 4.67 0.21 3.71 2.17 205 91 (lottery) 0.53 0.29 4.72 4.09 0.23 5.73 2.38 Sample average 0.49 0.29 4.58 4.19 0.22 4.33 2.24 Please cite this article in press as: Ajayi, O.C. et al. Auction Design for the Private Provision of Public Goods in Developing Countries: Lessons from Payments for Environmental Services in Malawi and Indonesia, World Development (2012), doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2011.12.007 8 WORLD DEVELOPMENT Table 7. Environmental outcomes (out of 50 trees), Malawi Tree survival (6 months) Auction treatment Tree survival (1 year) N Mean Min Max 171 82 171 40.6 42.5 32.4 3 16 0 50 50 50 Overall, households that received a contract under the auction tend to be slightly worse off than the sample average. Thus, it appears that in the Malawi setting, contract recipients were slightly less wealthy than the average household, particularly when considering only allocation under the auction. An assessment of the livelihood impacts of implementing a contract is therefore important to determine whether such a distribution pattern is desirable from an equity standpoint. If contracts make landholders better off, then allocation to the relatively poorer households may help achieve ancillary poverty alleviation objectives. Though contracts are ongoing, analyzing results from the first two monitoring periods offers some insights into the environmental effectiveness of the program. The primary environmental outcome of interest is the number of surviving trees, which is presented in Table 7. On average, 80% of trees survive the first six months of the contract. This number drops to 65% after the first year. However, underlying this number is a wide variation in tree survival. Through the first year of the contract, some landholders keep all trees alive, while others have very poor performance. The total number of contract holders presented in Table 7 is lower than the original number of recipients. Due to various events, five people quit the program in the first six months, only one of whom did not ever plant the trees. 6. CASE STUDY COMPARISONS AND IMPLICATIONS While the auction designs implemented in Indonesia and Malawi were similar, the context of implementation and the content of the PES contracts allocated were very different. A systematic comparison of similarities, differences, and results can help suggest areas where future research is most urgently needed, and also consolidate current available information for those wishing to implement conservation auctions of their own. Throughout this section, we raise open questions that the two case studies cannot resolve. We also return to the potential concerns surrounding auctions in developing country contexts, which were presented in Section 4: (a) understanding the bidding strategy, (b) information asymmetries, (c) power imbalance, and (d) distributional equity. (a) Comparison of implementation and context Both auctions used a uniform price, sealed bid auction format, with the clearing price determined by the first rejected bid, which makes truth-telling a dominant strategy. In Indonesia, participants were given a chance to gain experience with the mechanism through seven trial or learning rounds that preceded the final allocation round. With repetition, bids fell on average, lowering the clearing price in the auction. Whether the final-round price was better for overall program outcomes than the first-round price is difficult to determine without observing contract performance for both groups. Among auction participants who received a contract, those who would have received one had the first round been binding did slightly but insignificantly better in compliance terms than did contract recipients who would not have received a contract in the first round. This difference is a function both of changes in selection and changes in the clearing price over the bidding rounds. Future implementation of PES programs in developing countries, preferably using an experimental design, is needed to assess the benefits of repeated bidding sessions. The effect of multiple bidding rounds raises issues of participant understanding of the mechanism. The comparison of the auction and the posted price offer compliance outcomes from the case study in Malawi give us the clearest indication of whether participants understood the auction. Compliance under the auction was significantly higher than compliance under the posted price offer treatment. This indicates that the auction had sorting power, which implies that participants must have understood the bidding incentives to at least some extent. What is relatively more surprising about the findings from that study is that the posted offer treatment appears to be associated with less understanding of the market mechanism’s implications. A survey measure collected after the auction implementation provides further evidence on the relationship between participant understanding and bidding behavior. A psychological measure of cognitive ability was collected using a reverse digit span test, which measures ability to abstractly manipulate numbers. The resulting score was only weakly correlated, both linearly and nonlinearly, with bids. This suggests that there was no systematic relationship between how “smart” an individual is and his or her ability to formulate a bid. Another important difference between the two case studies lies in the contract, both in terms of the costs it imposes on the landholder and the incentives it offers. First, the erosion mitigation contract in Indonesia consisted primarily of labor inputs and had no direct impact on production, beyond the costs of labor diverted away from coffee production. In Malawi, the use of the land for tree growing implied an impact on production for landholders without surplus landholdings. Individuals were given the option of intercropping with the trees to minimize the effects on production. These differences in the contracted activities are consistent with a greater heterogeneity in opportunity cost in the Malawi case. In both cases, land holders perceived some private benefits associated with the contract activities, such as improved soil fertility. Second, the contract payments in Indonesia are conditional on the completion of particular activities that are associated with reducing erosion, such as terracing. In Malawi, the contract payments are conditional on tree survival outcomes. As Zabel and Roe (2009) discuss, placing PES incentives on actions or on outcomes trades off risk sharing with incentives: paying for actions reduces the risk borne by the landholder, but distorts incentives away from the socially desired outcome. Comparisons across the cases are complicated by the differences in the incentives delivered by the contracts. In Indonesia, a threshold incentive was delivered with two thresholds determining payments, the first at the mid-point (6 months) and the second after a year. Thus payments were all-or-nothing at both of these evaluation points, with a discontinuous incentive for effort around the thresholds. Such a contract structure is inefficient relative to the marginal performance incentives delivered by the Malawi tree planting contract, which rewarded contract holders on the margin (per surviving tree). Threshold incentives place additional risk on the landholder and deliver no incentive to exert effort beyond the amount required to achieve the threshold. The Indonesia contract also delivered a third of the payment upfront. While an upfront payment may be necessary to alleviate liquidity constraints, Please cite this article in press as: Ajayi, O.C. et al. Auction Design for the Private Provision of Public Goods in Developing Countries: Lessons from Payments for Environmental Services in Malawi and Indonesia, World Development (2012), doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2011.12.007 AUCTION DESIGN FOR THE PRIVATE PROVISION OF PUBLIC GOODS 9 some minimal input or effort requirement to obtain a payment can help reduce enrollment by landholders with no intention of completing the contract. Provision of in-kind inputs for contract implementation may address the liquidity constraint concern without generating excess sign-up. The contracts allocated under the case studies also differ in their length. The Indonesia contract lasted only for one year, thus covering only one agricultural cycle. As opportunity cost fluctuates with agricultural seasons, compliance patterns are also likely to vary. In Malawi, where the contracts last for three years, we may be able to observe more about opportunity cost fluctuations, though the measured outcome of tree survival is a cumulative measure of all prior shocks. The length of these contracts was designed with the particular investment that they require in mind. While the erosion mitigation investments in Indonesia require some maintenance, they are fairly durable. Consequently, paying for their construction is likely to result in a stream of future environmental benefits. Similarly, in Malawi, the primary costs to establishing trees accrue during the first few years of growth. Beyond that point, the trees will be established enough to survive with only minimal additional investment. While both land use activities do have ongoing costs beyond the period of the contract, these longer term costs are very small compared to the costs covered during the contract. implementation, default rates were around 40%. This second period of the contract coincided with the coffee harvest, which was better than previous years, both in terms of prices and yields. Consequently the higher opportunity cost of implementation once coffee profits were known may have contributed to high default rates. The compliance patterns in Indonesia suggest an additional issue with auction bidding, which is that individuals treat the conservation contract as an option contract. With uncertainty about future income opportunities, individuals may accept a contract price that is too low for a good state of the world but that is a supplement to income in a bad state of the world. Then, after the uncertainty is resolved (when harvest time arrives, for example), landholders decide to comply if other income is bad or to default if other income is good. The structure of costs under the Malawi tree planting contracts makes this an unlikely explanation for results in that case. High fixed costs at the start of the contract and the lack of upfront cash payments makes the option value of the contract exceedingly low. Where option value may present a challenge to compliance, an incentive scheme that considers these fluctuations in costs may be able to reduce default relative to a static contract. (b) Comparison of bidding and compliance results In Section 4, we outlined a number of potential issues for the implementation of conservation auctions in developing countries. First, as discussed, results from Indonesia and Malawi appear as if understanding of the auctions was sufficiently high to reveal private information (see also Jack, 2009, 2010). Second, we raised the concern that ex ante expectations of opportunity cost might be poor predictors of ex post opportunity cost. Low compliance rates in Indonesia are consistent with this concern. However, if instead of binary measures of compliance, we look at a continuous measure of implementation, then the picture is less stark. Even noncompliant individuals in the Indonesia case study completed, on average, over 80% of the contract. Better measures of ex post shocks and their effect on compliance have implications for contract design and allocation. Third, another concern described above relates to power structures and social pressure. Our results do not offer clear evidence on how important these factors were in either bidding behavior or compliance results. In the Indonesia case, the relatively high default rates close to the end of the contract period are not what we would expect if individual compliance decisions were influenced by power structures. In both cases, an effort was made to emphasize the voluntary nature of the contracts and the ability to exit at any point without incurring any penalty aside from foregone future payment. Neither case varies the power structure systematically, making it difficult to hypothesize about the importance of these factors. Fourth, we discussed the distributional implications of allocation based on cost rather than some explicit equity criteria. As stated above, much of the concern with distributional equity in PES programs assumes that the contracts make individuals better off. While this may be the case, little empirical evidence is available to support the claim. The structure of the price setting mechanism and follow up qualitative interviews suggest that individuals are receiving a surplus above their true minimum willingness to accept. A follow up survey is planned for program participants in Malawi, with the intention of measuring impacts of the contract on recipients. All PES programs should take steps to evaluate livelihood impacts, preferably with clean evaluation methods that measure impacts against a no-PES counterfactual. Turning to the results in both of the case studies, we observe around 40% of bidders receiving contracts in both settings (41% in Indonesia and 38% in Malawi). We also observe a steeper than exponential distribution of bids in both settings, with greater variability in bids at the top end of the distribution. Direct comparison of prices is meaningless given the differences in wealth levels and in the requirements of the contracts. Calibration of auction bids to accounting style estimates of opportunity cost suggests an interesting regularity across the settings. In both cases, the calculation of opportunity cost using market prices brackets the mean bid. Several possible interpretations of this result present themselves. First, individuals may be bidding accurately and opportunity costs may vary above and below the market value of contract implementation due to shadow prices on land, labor, and other inputs. Alternatively, bidders may be using a similar approach to calculating opportunity cost—adding up land, labor, and other input expenses at market values—and benchmarking bids to that value. In terms of contract compliance, both contracts show a decline in compliance over time, though likely for different reasons. In Malawi, compliance measured by tree survival shows a steady decline over the course of the contract. Some death rate for newly planted seedlings is expected, and the fairly steady decline in survival may be attributed to natural patterns in addition to landholder effort. In the case of tree survival, effort costs will also vary with the agricultural season, with the most difficult survival period coming between months 6 and 12, when farmers must water the seedlings manually. Continued monitoring through the end of the contract may offer additional insights. While the environmental benefits resulting from the programs have not been fully quantified (see Jack (2010) for an estimate of projected carbon sequestration in Malawi), the small scale of the pilot programs makes it unlikely that they would generate meaningful changes in environmental services. In Indonesia, compliance rates were high through the midpoint of the contract. During the final six months of contract (c) Implications for the future use of auctions in developing countries Please cite this article in press as: Ajayi, O.C. et al. Auction Design for the Private Provision of Public Goods in Developing Countries: Lessons from Payments for Environmental Services in Malawi and Indonesia, World Development (2012), doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2011.12.007 10 WORLD DEVELOPMENT We presented simplified comparisons of socioeconomic indicators between those who received contracts and those who did not for each of the cases. In both settings, distributional patterns were weak. On some measures, contract recipients appeared to be slightly better off in the Indonesia case and worse off in the Malawi case than the average household in both settings. Thus, if contracts truly do make households better off, then the Indonesia allocation may have been very slightly regressive while the Malawi allocation may have been slightly progressive. The results are weak, both in terms of statistical significance and magnitude. Distributional concerns do not appear to be a major factor in either of the cases presented. 7. CONCLUSION AND POLICY IMPLICATIONS Auctions present a promising tool for allocating conservation contracts in settings where opportunity costs are difficult to observe. However, evidence on their performance in developing country settings is scarce. Here we summarize two early applications, both implemented by the World Agroforestry Centre (ICRAF), one in Indonesia, and one in Malawi. Findings suggest that auctions may be useful for sorting individuals by opportunity cost, but that market mechanisms may perform in nonstandard ways in these settings, making piloting particularly valuable. These results may be due to participant understanding of the mechanism, to the difficulties in evaluating opportunity cost, or to the prevalence of ex post shocks is an open question. The case studies and discussions presented above suggest a few clear ways forward for the implementation of auctions in developing countries. First, more research is clearly needed to better understand the benefits of such an approach relative to alternatives, and to develop further practical guidance on the specific contexts in which auctions are most likely to succeed. Section 4 outlines a number of conditions that, according to theory, will affect the benefits of an auction approach to contract allocation. Further evidence on their practical relevance is needed. Second, experience and understanding are likely to be important and market mechanisms may not perform as expected in developing country settings. While the experiment in Malawi clearly demonstrates that different mechanisms may offer tradeoffs along quantity–quality lines, none of our results can speak to the price sensitivity of compliance outcomes. Under a given allocation of contracts, the relationship between contract prices and contract outcomes is an empirical one that deserves further investigation. For each case, we observe responses to a single price point. Experimentation with how supply and compliance respond to different contract prices has the potential to improve how future PES programs allocate contracts and set contract prices. NOTES 1. The Katoomba Group (http://www.katoombagroup.org) attempts to provide inventories of PES programs and potential in countries around the world. 2. Throughout the article, the emphasis is on targeting landholders with the lowest opportunity cost of supplying environmental services. While the benefits associated with the supply of environmental services may also vary across landholders, these are typically not a large source of information asymmetry between the landholder and the implementing organization. Ferraro (2008) provides a discussion of how benefit measures can be incorporated into auction design. Explicit targeting on environmental benefits is most important where the correlation between environmental benefits and opportunity cost is low. 3. Payments may also have a number of unintended effects. By changing the prices on certain activities, PES programs may create spillovers that include greater environmental degradation in nearby, but uncontracted, areas. This phenomenon is commonly referred to ask leakage (for relevant discussion, see Pattanayak, Wunder, & Ferraro, 2010). On the other hand, payments may generate positive spillovers if they, for example, convey information about the value of the environmental service generating activity (Ajayi, Akinnifesi, Sileshi, Chakeredza, & Mgomba, 2009). 4. Reverse auction” is a term that has been adopted by many PES practitioners. Referring to these types of auctions as procurement auctions is more consistent with the economics literature. The environmental service buyer is procuring service provision from the landholders. 5. Theoretically, the bidding incentives are the same as for an English (open outcry, ascending) auction. 6. An alternative to a uniform pricing rule is a discriminatory pricing rule. A second price scoring rule in which each winning bidder is paid the price of the next lowest bidder preserves incentive compatibility. A discriminatory price rule has the advantage of transferring less surplus to the bidders, improving the cost effectiveness of the allocation. 7. Theoretically, both approaches result in incentive compatible bidding, except in the case of a nonbinding budget constraint. Schilizzi and LataczLohmann (2007) offer further discussion of these alternative constraints. 8. The problem of allocation when opportunity costs are uncertain is not unique to auctions. Fixed price programs may suffer from the same challenge of low compliance when ex post costs differ from ex ante estimates. 9. All data in this section are presented in other publications, though the discussion here is original. New analyses are, in some cases, undertaken to improve the comparability of the two case studies. 10. To the best of our knowledge, the Indonesia case study was the first such implementation. The Malawi case study was implemented around the same time as another auction for environmental service contracts implemented by Rohit Jindal in Tanzania. The Malawi case study is the only one of these that employs an experimental design to evaluate the auction performance relative to an alternative mechanism. 11. This type of behavior would only be anticipated should the contract value place an incentive on surviving seedlings higher than the cost of a replacement seedling. Because the contract price would be set after determining the contract content, we chose to mitigate the risk of this outcome by choosing a species not available in local markets. Please cite this article in press as: Ajayi, O.C. et al. Auction Design for the Private Provision of Public Goods in Developing Countries: Lessons from Payments for Environmental Services in Malawi and Indonesia, World Development (2012), doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2011.12.007 AUCTION DESIGN FOR THE PRIVATE PROVISION OF PUBLIC GOODS 12. The approach used in the Malawi case study is an example of randomized field experiment methodology applied to conservation programs. While such approaches are increasingly used in health and other development fields, they are less frequently used for environmental and conservation applications (Ferraro, 2009). 11 13. The prevalence of food aid programs in Malawi makes measures of food shortage an imperfect indicator of economic well being. In our sample, months of food shortage is negatively correlated with both educational attainment and production of cash crops, two positive indicators of socioeconomic well being. REFERENCES Ajayi, O. C., Akinnifesi, F. K., Sileshi, G., Chakeredza, S., & Mgomba, S. (2009). Integrating food security and agri-environmental quality in Southern Africa: Implications for policy. In I. N. Luginaah, & E. K. Yanful (Eds.), Environment and health in sub-Saharan Africa: Managing an emerging crisis. Netherlands: Springer. Antle, J. M., & Stoorvogel, J. J. (2006). Predicting the supply of ecosystem services from agriculture. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 88(5), 1174–1180. Bulte, E. H., Lipper, L., Stringer, R., & Zilberman, D. (2008). Payments for ecosystem services and poverty reduction: Concepts, issues and empirical perspectives. Environment and Development Economics, 13(3), 245–254. Coase, R. H. (1959). The Federal Communications Commission. Journal of Law and Economics, 2, 1–40. Coase, R. H. (1960). The problem of social cost. The Journal of Law and Economics, 3, 1–44. De Janvry, A., Fafchamps, M., & Sadoulet, E. (1991). Peasant household behaviour with missing markets: Some paradoxes explained. The Economic Journal, 101(409), 1400–1417. Engel, S., Pagiola, S., & Wunder, S. (2008). Designing payments for environmental services in theory and practice: An overview of the issues. Ecological Economics, 65(4), 663–674. Ferraro, P. J. (2008). Asymmetric information and contract design for payments for environmental services. Ecological Economics, 65(4), 810–821. Ferraro, P. J. (2009). Counterfactual thinking and impact evaluation in environmental policy. In M. Birnbaum, & P. Mickwitz (Eds.), Special issue on environmental program and policy evaluation. New Directions for Evaluation (Vol. 122, pp. 75–84). Jack, B. K. (2009). Auctioning conservation contracts in Indonesia: Participant learning in multiple trial rounds. Center for International Development Working Paper 35. Jack, B. K. (2010). Allocation in environmental markets: A field experiment with tree planting contracts in Malawi. SSRN Working Paper Series. Jack, B. K., Kousky, C., & Sims, K. R. E. (2008). Designing payments for ecosystem services: Lessons from previous experience with incentivebased mechanisms. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 105, 9465–9470. Jack, B. K., Leimona, B., & Ferraro, P. J. (2009). A revealed preference approach to estimating supply curves for ecosystem services: Use of auctions to set payments for soil erosion control in Indonesia. Conservation Biology, 23(2), 358–367. Latacz-Lohmann, U., & Schilizzi, S. (2005). Auctions for conservation contracts: A review of the theoretical and empirical literature. Technical Report, Scottish Executive Environment and Rural Affairs Department. Leimona, B. (2010). Designing a procurement auction for reducing sedimentation: A field experiment in Indonesia. Indonesia, Bogor: World Agroforestry Centre – ICRAF, SEA Regional Office. Leimona, B., Joshi, L., & van Noordwijk, M. (2009). Can rewards for environmental services benefit the poor? Lessons from Asia. International Journal of the Commons, 3(1), 82–107. List, J. A. (2003). Does market experience eliminate market anomalies?. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 118(1), 41–71. List, J. A., & Shogren, J. F. (1999). Price information and bidding behavior in repeated second-price auctions. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 81(4), 942–949. Montgomery, W. D. (1972). Markets in licenses and efficient pollution control programs. Journal of Economic Theory, 5(3), 395–418. Pattanayak, S. K., Wunder, S., & Ferraro, P. J. (2010). Show me the money: Do payments supply ecosystem services in developing countries?. Review of Environmental Economics and Policy, 4(2), 254–274. Perrot-Maı̂tre, D., & Davis, P. (2001). Case studies of markets and innovative financial mechanisms for water services from forests. Washington, DC: Forest Trends and the Katoomba Group. Schilizzi, S., & Latacz-Lohmann, U. (2007). Assessing the performance of conservation auctions. Land Economics, 83(4), 497–515. Stavins, R. N. (1995). Transaction costs and tradeable permits. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, 29(2), 133–148. Vickrey, W. (1961). Counterspeculation, auctions, and competitive sealed tenders. Journal of Finance, 16(1), 8–37. Vickrey, W. (1976). Auctions markets and optimum allocations. In Y. Amihud (Ed.), Bidding and auctioning for procurement and allocation. New York University Press. Wunder, S., Engel, S., & Pagiola, S. (2008). Taking stock: A comparative analysis of payment for environmental services programs in developed and developing countries. Ecological Economics, 65(4), 834–852. Zabel, A., & Roe, B. (2009). Optimal design of pro-conservation incentives. Ecological Economics, 69(1), 126–134. Zilberman, D., Lipper, L., & McCarthy, N. (2008). When could payments for environmental services benefit the poor?. Environment and Development Economics, 13(03), 255–278. Please cite this article in press as: Ajayi, O.C. et al. Auction Design for the Private Provision of Public Goods in Developing Countries: Lessons from Payments for Environmental Services in Malawi and Indonesia, World Development (2012), doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2011.12.007