ZEF Bonn Could Tighter Prudential Regulation Have Saved

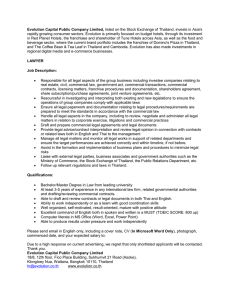

advertisement