AIR FORCE HANDBOOK 10-222, VOLUME 22 20 April 2011

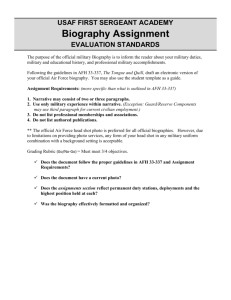

advertisement