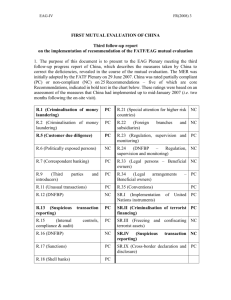

PREPAID CARDS, MOBILE PAYMENTS AND INTERNET-BASED PAYMENT SERVICES

advertisement