JHAZ Journal of Hazard Mitigation and Risk Assessment Multihazard Mitigation Council

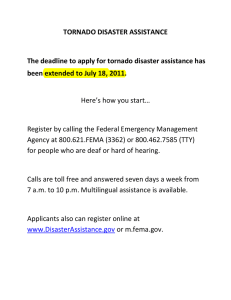

advertisement