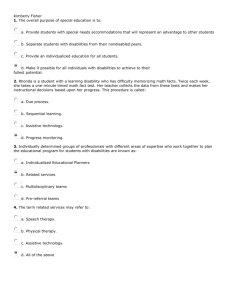

A New Vision for Saskatchewan for People with Intellectual Disabilities

advertisement