Document 12028375

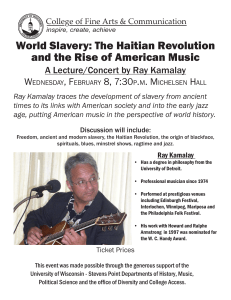

advertisement