I S S U E N O. 11 W I...

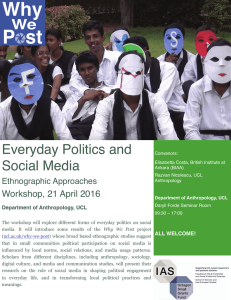

advertisement