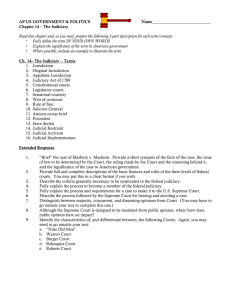

COMMISSION JUDICIAL APPOINTMENTS JUDICIAL DIVERSITY

advertisement