Document 11985342

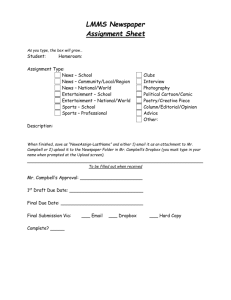

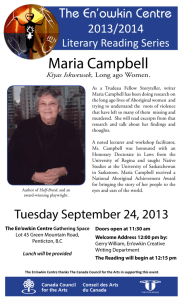

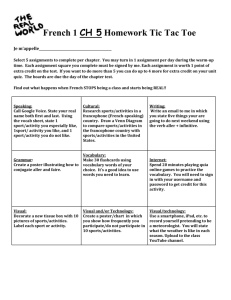

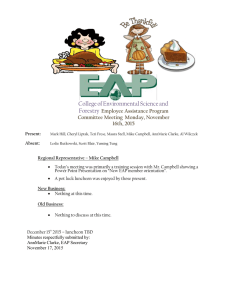

advertisement