Document 11970452

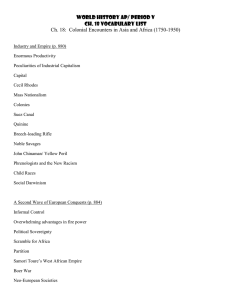

advertisement