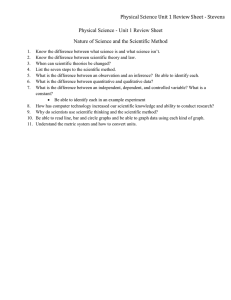

Working Paper

advertisement