Example: Drawing polygons.

advertisement

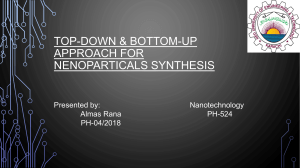

Example: Drawing polygons. Requirements: a program to draw a regular polygon with a given number of sides, and a given side length. These requirements are not complete. What is the maximum and minimum permissible side length? Min number of sides: 3 Maximum number: 8 (for example). This is a design problem. You have to put "parts" together to get a program that satisfies the requirements. We can work at this from the top down and from the bottom up. Top-down approach: Think about what parts or tasks need to be done to meet the requirements. Then think about what subparts and subtasks need to be done to implement the parts or tasks. And keep going this way, dividing into smaller and smaller parts, until we get to things we already have. Pros: Tends to lead to clean, understandable designs. Each part has well-defined purpose, relative to the requirements. Cons: One problem is that you don't necessarily know that you will get to things you have (or can get). So you have to have an idea what's possible and what's available. The other problem is that this process can indicate the need for slightly different subsystems, that in fact could be the same, which would be more economical. (E.g., sorting numbers and sorting character strings could be done by one sort routine.) This is more of a problem with team projects. Bottom-up approach: We start with what we have, and (based on our knowledge of how systems are implemented) we put them together to make useful components for building systems. We put these into libraries that designers can use. We keep building up this way. You get reusable components more easily than with top-down approach, but good bottom-up design requires prior experience with top-down (so you know what components are likely to be useful). So for example the Myro library is useful for controlling scribbler-like robots. And when you design a robot control program, these are basic-level components you will be using (as well as other libraries). In the case of the polygon program, we can do a little top-down and a little bottomup. Obviously, we need to be able to draw straight lines of a given length, and to turn through a given angle. Note that Myro does not provide these operations. In figuring out how to do something, it is always helpful to think "How would I do it?" Then look at the individual steps. This is especially useful for robots, because we are physical, mobile objects like the robots. Put yourself in the robot's place. Start simple, say with a square. Make sure to check boundary conditions (minimum and maximum values) to make sure it works. This is where programs often go wrong, because they tend to be special cases. Related: off-by-one errors: Usually means you go through a loop one too many times or one too few times. Standard coding practices can help avoid these errors in common cases. You always do the common cases the same way, which you know works. Random numbers: Most programming languages provide (via a library) a pseudo-random number generator. This is a deterministic number series that looks random. Random numbers are useful in games, simulations, and many other applications. To get real a random starting point (seed), either get a genuinely random number (radioactive decay), or use something that is effectively random, like the number of milliseconds from the start of the program until the first interaction. Or the number of msec. from some fixed time in the past until the program started.