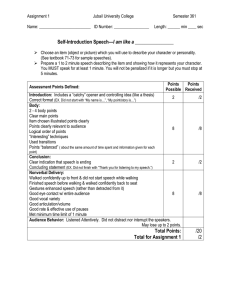

Pausing in Dialogues and Read Speech in Swedish:

advertisement

Pausing in Dialogues and Read Speech in Swedish:

Speakers’ Production and Listeners’ Interpretation

Beáta Megyesi and Sofia Gustafson-Čapková

Centre for Speech Technology

Department of Speech, Music and Hearing

KTH

S-10044, Stockholm, Sweden

bea@speech.kth.se

Department of Linguistics

Computational Linguistics

Stockholm University

S-10691 Stockholm, Sweden

sofia@ling.su.se

Abstract

In this study, we investigate the characteristics of pausing in

speakers’ production and listeners’ interpretation in three different speaking styles in Swedish: elicited spontaneous dialogues,

professional and non-professional news reading. Considerable

attention is given to the positions in which pauses can appear,

in particular their discourse context regarding theme shift. We

show that the acoustic silent intervals that are perceived by the

listeners correlate with the discourse structure, while perceived

pauses having an acoustic silence in the speech signal, correlate

to the duration of the acoustic silence.

The results show clear differences between the speaking

styles. In reading, the majority of acoustic pauses are perceived

and the majority of both the acoustic and perceived pauses are

located at theme shift. In dialogues, on the other hand, few

acoustic pauses are perceived by the listeners and the majority of both the acoustic and perceived pauses are positioned at

theme continuation. Furthermore, where many pauses are perceived by the listeners, such as in non-professional reading and

dialogues, we find long acoustic silent intervals.

1. Introduction

In the last decades, many studies have been carried out to investigate the characteristics of pausing. One reason is that pauses

often indicate prosodic phrase boundaries which highlight the

organization of the message [1], [2], [3], [4], [5], [6]. Therefore,

knowledge about the variation of pausing in different speaking styles is necessary for several applications, such as textto-speech systems, speech recognition, and dialogue systems

where the structure of the message can be crucial for good system performance.

The purpose of this study is to investigate the distribution

of pauses in Swedish in three different speaking styles: elicited

spontaneous dialogues, and news read by both professional announcers of radio news and non-professional readers. Questions addressed are what positions do silent intervals occur in

and where do people perceive those. Do the discourse environments in which acoustic silence appears have any effect on the

perceptual interpretation of pausing? In this study, pauses found

in the acoustic signal are compared to the pauses perceived by

listeners regarding frequency and position.

2. Background

Previous studies have shown that large differences can be found

in the characteristics of pausing across speaking styles.

Several studies report [3], [7], [8], [9] that the pause intervals in spoken language vary by different genres, e.g. spontaneous speech and reading aloud.

Spontaneous dialogues and the read version of the same text

have been compared for Swedish in [1] and for English in [3].

These studies reported that the number and the distribution of

pauses as well as the speech rate differs across the speaking

styles.

Hirschberg [3] reports that read speech is more rapid than

spontaneous speech when examining dialogues taken from the

American English ARPA ATIS 0 corpus and the transliteration

of these dialogues, read aloud by the same subjects. In [1], a

spontaneous dialogue and the read version of the same speech

in Swedish is compared and it is reported, among other results,

that the number and the distribution of pauses differs between

the speech styles.

In [8] and [9], the distribution and features of pauses in

professional news announcement, non-professional news reading and monologues have been compared. The results show

that spontaneous speech contains long and frequently occurring pauses, while professional announcing is characterized

by shorter and fewer pauses. Non-professional announcing

is placed in between those two polarities. The pauses occur

mainly in places relevant to the underlying message, e.g. at syntactic boundaries, and at semantically important words. However, pauses also occur in other positions. In those cases there

seems to be a preference for sites as e.g. in connection to conjunctions.

Fant & Kruckenberg [10] and [11] investigated pausing

phenomena in Swedish. They carefully examined durational

patterns and local F0-contours in nine sentences read by a pro-

fessional reader, and one sentence read by 15 non-professional

readers. They report that pause duration ranges between 50100 ms for short prompters and 1-2 seconds between sentences.

Normal pause duration within sentences ranges normally from

300 to 600 ms. Furthermore, they report that pauses at sentence

boundaries are usually prolonged and final lengthening is more

frequent at phrase boundaries than at sentence boundaries.

The relevance of pausing indicating clause and sentence

boundaries are also pointed out by Garman [12] and GoldmanEisler [13].

Swerts & Geluykens [6] showed that speakers in monologue discourse vary the duration and position of pauses on the

basis of information structure. Pauses occur between all topical

units, and directly after the topic-introducing phrase or clause.

In the following sections, we will describe a study on pausing in Swedish dialogues and read speech where we relate

acoustic silent intervals, the perception of pauses and the discourse environment of these two aspects of pausing.

3. Acoustic and Perceived Pauses in Three

Speaking Styles

This study focuses on differences between read speech and dialogues in three speaking styles:

professional news announcing

non-professional reading

elicited spontaneous dialogues

The material of read speech consists of recordings of

Swedish radio news [14] read by four professional and four

non-professional readers. The spontaneous speech material [15]

consists of recordings of two Swedish map task dialogues, each

with two dialogue participants. The materials consist of 920

words each.

To make a comparison of pauses between the three different speaking styles, we investigate three different dimensions

of communication – production, perception, and context – we

collected data from all three aspects:

To be able to investigate the discourse context of the acoustic and perceived pauses, we asked five subjects to annotate each

text material (without listening to the audio files) with discourse

labels marking theme shift. Four of the subjects were females,

of which one is a co-author to this paper with knowledge about

discourse structure. The other subjects had no expert knowledge

in linguistics.

4. The Distribution of Acoustic Pauses

The duration, frequency and position features of acoustic pauses

is reported in our previous study [16]. Here, we will give a brief

summary of the most important features found, that are relevant

for this study, as well as new results on the discourse context of

acoustic pauses.

The mean duration of the acoustic pause duration is lowest in the professional reading (271 ms), highest in the nonprofessional reading (561 ms) followed by the dialogues (538

ms).

Considering the frequency of acoustic pauses, the ratio of

word per acoustic pause is highest in the professional reading (77 words/pauses), while the non-professional reading (8.4

words/pauses) gets a slightly higher rate than the dialogue (5.5

words/pauses).

Although there are differences in the duration and frequency of pauses between the styles, the total length of the

speech files is approximately the same for the reading styles.

Hence, the time it takes to pronounce a word in average differs between the speaking styles suggesting greater variation in

speech tempo.

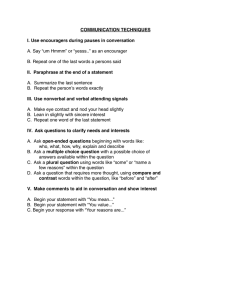

We can distinguish between different types of pauses such

as silent pause, and complex pause with breathing and/or swallowing. The study shows that the usage of the types differs

across the speaking styles as well as within each style, see Figure 1. For example, in the dialogues and the non-professional

reading above 60% of pauses are silent while in the skilled reading 83% of pauses are complex. The two different types (silent

acoustic data

subjects’ perception of pauses

data on discourse structure in the texts

In order to investigate the duration, frequency, type and position of acoustic pauses, the speech data was processed automatically by a pause detector. Silent intervals longer than or

equal to 100 ms were defined as acoustic correlate for pausing.

Pauses may include natural physical phenomena such as breathing and swallowing intervals. However, particles expressing

conversational support (e.g. mmm, aaa, aha) in dialogues are

not allowed inside pauses. The automatic detection was manually checked in order to properly include relevant disfluencies.

To find out what kind of acoustic pauses are perceived by

listeners, and where the perceived pauses occur, i.e. to examine the frequency and position of the perceived pauses, 20 human subjects annotated the position of what they identified as

a pause. They were asked to use different labels for long and

short pauses, and also mark cases where they were uncertain.

Two of the subjects were removed from the investigation because of their highly divergent results. Of the eighteen subjects total, there were eight females and ten males belonging

to different age groups and linguistic backgrounds. Eleven of

the subjects had some knowledge about linguistics but none of

them had ever participated in a similar experiment.

Figure 1: The amount of silent and complex pauses in professional and non-professional reading and in dialogues.

and complex pauses) are to a certain extent favored in different positions, as it was described in [16]. The position of the

acoustic pauses was labeled according to turn taking, theme

shift/continuation and the type of their following constituent:

phrase, clause or sentence. The discourse labeling was carried

out by the authors independently. The results were compared

and in case of conflicting analysis the authors agreed upon a

reconciled version of a data. In cases where a pause appears

inside a phrase, the PoS of the word was marked as well as

whether the word is a phrasal head or not.

The results show that in the professional reading, silent

pauses are rare (17% of all pauses are silent) and occur in

connection to theme continuation, mainly at sentence boundaries. In the non-professional reading, silent pauses also occur

at theme continuation (65.2%) but primarily at phrase boundaries, and secondly at clause and sentence boundaries. 34.8 %

of the silent pauses occur in connection to theme shift, mainly at

sentence boundaries. In the dialogues, 37% of the silent pauses

are found at turn taking often in front of conversational particles. Inside turns, silent pauses more frequently associated with

theme continuation than with theme shift. Additionally, in the

dialogues silent pauses also occur in front of head nouns and

adverbs.

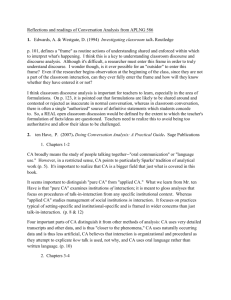

The results concerning the discourse context of silent

pauses are shown in Figure 2. Please, note that the two columns

for the dialogue represent results computed separately for theme

shift/continuation with no regard to turn taking, as well as for

turns that overlap with theme shift /continuation.

Figure 3: The discourse context of complex pauses: The position of complex pauses regarding theme shift and theme continuation in three speaking styles.

shows the annotation of the positions of the acoustic pauses.

TC – none of the five subjects labeled a theme shift

Majority TC – only one or two of the five subjects annotated a theme shift

Figure 2: The discourse context of silent pauses: The position

of silent pauses regarding theme shift and theme continuation

in three speaking styles.

The results on the position of complex pauses are illustrated

in Figure 3. Complex pauses in professional news announcing

can be found in connection to theme shift at sentence boundaries

(70%). The rest can be found at theme continuation, mostly

at sentence boundaries and between noun phrases in a list. In

the non-professional reading, 61% of complex pauses correlates

with theme continuation at sentence and clause boundaries and

in connection to noun phrases. The remaining part occurs in

theme shifts at sentence boundaries. In the dialogues, the distribution of turns, theme shift and theme continuation in connection to pauses are relatively even. Pauses can be found in

phrasal heads: nouns, or adverbs preceded by hesitation particles, and in connection to overlapping speech, conversational

particles, hesitations, etc.

As mentioned, the discourse annotation in [16] was done

by the authors only. To get a more confident annotation, we let

five subjects independently annotate the pure text materials for

theme shift (TS). Annotators indicated TS with a mark and nonmarked intervals are assumed to represent theme continuation

(TC). Interannotator agreement was computed for all materials

and gave a kappa value of K = 0.82 for the news texts, and K

= 0.79 for the dialogues. In both cases, the values indicate high

interannotator agreement.

With this new discourse data, it is possible to give a picture

of the correlation between pausing and TS versus TC in the discourse, as well as the continuum between TS and TC. Figure 4

Majority TS – three or four subject labeled a theme shift

TS – all five subjects agreed on a theme shift

In this task, no marking of turn boundaries was performed.

As is shown in Figure 4, the results from this extended annotation task show the same tendencies as the earlier investigation,

described above; The majority of the acoustic pauses in the

professional reading style are corresponding to a TS position,

in the non-professional reading still a majority of the acoustic

pauses corresponds to a TS position but to a lesser extent than in

the professional reading; In the dialogue, however, the acoustic

pauses rather occur at TC positions.

Figure 4: Acoustic pauses and discourse context: The discourse

position of acoustic pauses in the three speaking styles.

5. The Distribution of Perceived Pauses

The distribution of the perceived pauses, labeled by the

eighteen subjects, are to a large extent evenly distributed

across the speaking styles, see Figure 5.

The average

words/perceived pauses ratio is highest in the professional

reading (12,2 words/perceived pause) followed by the dialogues (11.4 words/perceived pauses), and lowest in the nonprofessional reading (8.2 words/perceived pauses).

Figure 5: The words/perceived pauses ratio in professional

reading, dialogue, and non-professional reading.

Where do the subjects perceive pauses in the different

speaking styles? Figure 6 illustrates the distribution of the

theme shift/continuation continuum of the three speaking styles

in a similar way as it was described for the position of acoustic

pauses in the last part of Section 4. The results also show that

in the reading styles most of the perceived pauses are located

at theme shift, while in the dialogues we found the position of

perceived pauses at theme continuation.

Figure 7: The ratio of word/acoustic and perceived pause in

professional and non-professional reading, and in dialogue.

+ '

! ! "$#%'&(- #.*) "#% ( (, /&0 * !1+ ! #!&("$#% '&(' " *#%) "#% ' 0

*)

(1)

(2)

The mean of the recall and precision rates for each style

is shown in Figure 8 below. We can see that in the professional

reading, a considerable number of acoustic pauses are perceived

as a pause by the subjects, but many of the perceived pauses

does not have any correlates in acoustic silence. In the nonprofessional reading, almost every acoustic pause is perceived

by the listeners, and also the majority of the perceived pauses

corresponds to silent intervals in the speech signal. In the dialogues, on the other hand, few acoustic pauses are perceived but

many of the perceived pauses match the acoustic silence.

Figure 6: Perceived pauses and discourse context: The discourse position of perceived pauses in the three speaking styles.

6. The Correlation between Acoustic and

Perceived Pauses

What acoustic pauses are perceived and what are not? In Figure 7, the words/pauses ratio for acoustic as well as for perceived pauses is shown. It is clear that the correlation of the

acoustic and perceived pauses varies across the speaking styles.

In the professional reading, the amount of perceived pauses are

much larger than acoustic pauses, while in the dialogues we find

the opposite relation. The difference between the acoustic and

perceived pauses is not as striking as in the professional reading.

In the non-professional reading, on the other hand, the amount

of perceived and acoustic pauses is comparable.

To give an overall picture of the correlation between the

acoustic and perceived pauses, we counted recall and precision

rates for each of the eighteen subjects within every speaking

style. Recall describes the percentage of the acoustic pauses

that were actually perceived (see Equation 1), while precision

gives the percentage of perceived pauses that corresponds to

acoustic silence (see Equation 2).

Figure 8: Recall and precision rates for the perceived pauses in

the three speaking styles.

We also note that the deviation between the subjects’ interpretation of pausing differs across the speaking styles, see

Figures 9 and 10. In the professional news announcement, the

recall rate is high as well as the deviation between the subjects,

while the precision is low with agreement between the subjects.

In the dialogues, the relation appears to be the opposite. However, in the non-professional reading where both recall and precision rates are high, the deviation between the subjects is relatively small.

As we have seen there are acoustic pauses that are not perceived by listeners, and perceived pauses without any correlate

ing (52 cases) but very rare in the dialogues (2 cases), and nonexisting in the non-professional reading. The perceived pauses

without a silence correlate in the professional reading are located in 71% of the cases in connection to theme shift according

to the majority of the discourse annotators.

6.3. Not perceived acoustic pauses

Figure 9: Recall rates (%) for the three speaking styles.

When are acoustic silent intervals not perceived by more than

20% of the listeners as pauses? There are many such cases in

the dialogues, but only a few in the non-professional reading

and none in the professional reading, as it has been shown by

the precision rates for each speaking styles. If we look at the

position of those acoustic pauses that are not perceived by the

listeners in the dialogues, we find that the majority of the discourse annotators agreed on theme continuation in 58% of the

cases. Those acoustic pauses which position the majority of annotators regarded as theme continuation are shorter in average

(345 ms) than the overall pause duration for all the cases (530

ms).

7. Discussion

Figure 10: Precision rates (%) for the three speaking styles.

to acoustic silence, and lastly, cases where acoustic and perceived pauses coincide. The distribution of these three conditions differs between the speaking styles. Next, we will describe

those cases in detail and relate those to their discourse context.

6.1. Acoustic pause and perceived pause coincide

Acoustic pauses that are perceived by 75% to 100% of the listeners occur in every speaking style. In the professional reading, they are located in connection to theme shift in 100% of

the cases according to the majority of the discourse annotators.

In the non-professional reading, they can be found in 77 % of

the cases at theme shift according to the majority of annotators,

but also at theme continuation. When the pause is perceived at

theme continuation, we found that the acoustic silence interval

is shorter (466 ms) than the average duration of all cases (584

ms). In the dialogues, they occur in 79% of the cases at theme

continuation but we did not find any explanation in the duration

of these pauses.

6.2. Perceived pause without acoustic silence

Cases where 75% of the listeners perceived a pause without any

acoustic silence correlate are common in the professional read-

The high precision values of the non-professional reading and

the dialogue might be explained by longer pausing duration, 561

and 538 ms respectively, as compared to the professional reading with a mean duration of 271 ms. However, there are large

differences between the speaking styles. In the professional

reading, all acoustic pauses were found but also a great amount

of perceived pauses. The reading styles have similar recall rates

which indicates that subjects in the professional reading hear

about as many pauses as in the non-professional reading. This

might be due to the fact that the message organization is the

same in both speaking styles. In our study, non-professional

readers use silence to signal a structure while professional readers use other prosodic features. The listener can also chunk

the message according to a clear discourse structure. In the dialogue, however, there are many silent pauses that are ignored by

subjects. This might depend on the low correlation between the

acoustic pauses and the discourse structure. We might find an

explanation in that speakers in spontaneous dialogue use other

prosodic features, e.g. intonational and temporal variation, to

signal prosodic boundaries; perhaps the same features as we

can find in the professional reading.

Our results indicate that high recall mirrors a clear discourse structure, while high precision reflects longer acoustic

silent intervals. In the reading styles, we have high recall and

the majority of the discourse annotators agreed on theme shift.

High precision rates are found in those speaking styles where

the average duration of silent intervals are longer, namely in the

non-professional reading and the dialogue. Low precision in

the professional reading might be due to other prosodic features

such as intonational variations were used for prosodic phrasing.

Additionally, a possible explanation to the low recall in the

dialogue might be that the silent intervals often are not as relevant for the message structure as in the reading styles. The discourse structure in the dialogues is more opaque so the pauses

do not coincide with theme shift. This is also suggested by

the negative correlation between theme shift and acoustic pausing. Planning pauses are perhaps not perceived in the same way

as prosodic phrasing. In spontaneous speech, speakers perhaps

primarily use other prosodic features (such as intonational variations, segment lengthening, variation in tempo, etc) to signal

phrasing and discourse structure.

We did not find any correlation between pause duration and

the number of subjects who perceived silent intervals as a pause.

[4]

Hirschberg, J., “Communication and Prosody: Functional

Aspects of Prosody”, Speech Communication: Special Issue on Dialogue and Prosody, Terken, J., & Swerts, M.

(Eds.), 2001.

[5]

Ostendorf, M., “Prosodic Boundary Detection” Prosody:

Theory and Experiment, Studies presented to Gösta

Bruce, Kluwer Academic Publisher, 1997.

[6]

Swerts, M. & Geluykens, R., “Prosody as a marker of

information flow in spoken discourse”, Language and

Speech 37, 21-45, 1994.

[7]

Hirschberg, J., “Prosodic variation and discourse structure across speaking styles”, Prosody: Theory and Experiment, Studies presented to Gösta Bruce, Kluwer Academic Publisher, 1997.

[8]

Strangert, E., “Speaking style and pausing”, PHONUM,

Reports from the Department of Phonetics, University of

Umeå, 1993.

[9]

Strangert, E., “Clause Structure and Prosodic Segmentation”, FONETIK-93 Papers from the 7th Swedish Phonetics Conference, John Sören Petterson (ed), Uppsala, May

12-14, 1993.

8. Conclusions and Future Directions

In this study we investigated the phenomena of pausing in three

different speaking styles in Swedish: elicited spontaneous dialogues, professional news announcement and non-professional

reading. Additionally, we examined the discourse context that

corresponded to intervals of acoustic silence and listener perceived pauses. Our results show large differences across the

speaking styles. In the professional reading, all acoustic silence

intervals are found by the listeners, but a great number of perceived pauses do not have an acoustic correlate in silence. In the

non-professional reading, the majority of the acoustic pauses

are perceived by the listeners, and many of the perceived pauses

actually have an acoustic correlate. In the dialogues, on the

other hand, many acoustic pauses are not perceived as pauses by

the listeners but many of the perceived pauses have an acoustic

correlate in silence. Considering the discourse environment in

which the acoustic and perceptual pauses appear, we observed

that silence is perceived if it occurs in connection to theme shift,

while if the silence is found at theme continuation, the listeners

do not perceive those intervals as pauses. Not surprisingly, we

also showed that pause length have an effect on the the listeners perception; the longer the silent intervals are, the better the

chance that the perceived pause is actually an acoustic silent

interval.

Questions we find important to explore in future work concern intonational variation in connection to pausing and discourse structure. Since many perceived pauses do not seem to

have silence as a primary correlate, analysis of intonational patterns would shed more light on the importance of the intonational variations and their effect on prosodic phrasing.

Other fields for future work include the investigation of the

relation between the hierarchical discourse structure and pausing, as well as the closer examination of the syntactic environment of pauses and its relation to the discourse structure.

Acknowledgements

First of all, we would like to thank all the people without whom

this study would not see the light; Petur Helgason for the dialogue corpus, Swedish Radio for the Swedish news recordings,

the four non-professional readers and Mattias Heldner for his

help with the recordings of the non-professional readings. Also,

a big thank you to the participants in the listening tests and to

the subjects of the discourse annotation. Last, but not least,

many thanks to Rolf Carlson for the interesting and fruitful discussions, for his brilliant suggestions and valuable comments.

9. References

[1]

Bruce, G., “Modelling Swedish Intonation for Read

and Spontaneous Speech”, Proceedings of International

Congress on Phonetic Sciences, Vol. 2 pp. 28-35, 1995.

[2]

Deese, J., “Pauses, prosody and the demands of production in language”, Temporal Variables in Speech, Studies

in Honour of Frieda Goldman-Eisler, Hans & Raupach,

Manfred (Eds.), Mouton Publishers, 1980.

[3]

Hirschberg, J., “Prosodic and other acoustic cues to speaking style in spontaneous and read speech”, Proceedings of

International Congress on Phonetic Sciences, Vol. 2, pp.

36-43, 1995.

[10] Fant, G. & Kruckenberg, A., “Preliminaries to the Study

of Swedish Prose Reading and Reading Style”, In STLQPSR 2/1989 (April-June), Speech Transmission Laboratory (Department of Speech, Music and Hearing), Royal

Institute of Technology, Stockholm, Sweden, 1989.

[11] Fant, G., Kruckenberg, A., & Liljencrants, J, “Acousticphonetic Analysis of Prominence in Swedish, In Botinis,

A. (Ed.), Intonation: Analysis, Modelling and Technology,

Kluwer Academic Publishers, 2000.

[12] Garman, M., “Psycholinguistics”, Cambridge University

Press, 1990.

[13] Goldman-Eisler, F., “Pauses, Clauses, Sentences”, Language and Speech, 15:2, 1972.

[14] Recordings of Swedish Radio News, Swedish Radio,

1999-2000.

[15] Helgason, P., “Stockholm Corpus of Spontaneous Speech”,

Department of Linguistics, Stockholm University, forthcoming.

[16] Gustafson-Čapková, S. & Megyesi, B., “A Comparative

Study of Pauses in Dialogues and Read Speech”, Proceedings of Eurospeech 2001, Volume 2, pp. 931-935, Aalborg, Denmark, September 3-7, 2001.