Autopia's End: The Decline and Fall of Detroit's Automotive Manufacturing Landscape

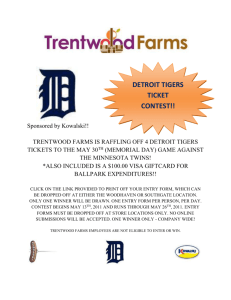

advertisement