I LAND BANKING AS A TOOL FOR THE ECONOMIC

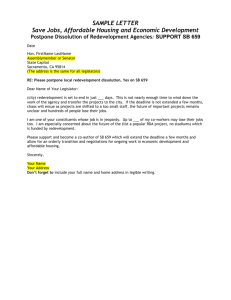

advertisement