A Systenl That Monitors Blowing Snow in Forest Canopies

advertisement

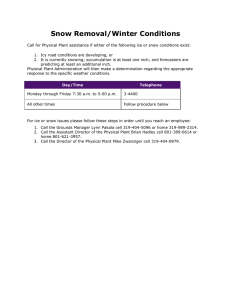

This file was created by scanning the printed publication. Errors identified by the software have been corrected; however, some errors may remain. A Systenl That Monitors Blowing Snow in Forest Canopies R. A. Schmidt and Robert L. Jairell 1 Abstract--An electronic system that connects a desktop computer (PC) to tower-mounted arrays of snow particle counters I!Irovides a new approach to an old problem--why more snow accumulates In sma" openings than in the surrounding forest. Each photoelectric sensor generates a pulse for a particle passing through its light beam. These are counted by a microprocessor system that passes the sums to the PC. Preliminary measurements in both a clearing and the forest upwind show counts Increasing with height in the 15-m region centered near the mean canopy height (18 m). Why do small forest clearings accumulate more snow than adjacent stands? This question has puzzled researchers since studies began at the Fraser Experimental Forest in Colorado. They developed two explanations: (1) snow trapped by the forest canopy (inte.rception) evaporates in place, re.ducing snowpack on the forest floor, and (2) wind guides more snowfall (including interception) jnto the clearings (aerodynamic re.distribution). Interce.ption was first favored as the likely explanation. Goode.11 (1959) measured evaporation of interc.epted snow, and c.alled for detailed analytical studie.s of the process (Goodell 1963). However, intensive measurements of snowpack on the Fool Creek watershed suggested that timber harvest did not increase total snow accumulation, compared to the East St. Louis control watershed (Hoover and Leaf 1967). This evidence supported the aerodynamic redistribution hypothesis, because reducing interception loss by timber harvest should increase total snow accumulation. Researchers led by Charles Troendle have continued to measure the peak water equivalent of snow on Fool Creek and East St. Louis. 'Vith precision increased by a longer measuring period, it now appears that total snow accumulation on Fool Creek did increase about 9% after harvest. This increase approaches the 12% increase Hoover and Leaf (1967) said was expected, assuming all increased snowpack (and thus streamflow) resulted entirely from reduced interception loss (Troendle and King 1985). Analytical experiments on the evaporation of blowing snow in the plajns environment (Schmidt 1972, 1982; Tabler and Schmidt 1972; Tabler 1975), show how strongly surface area affects the process. The results support the likelihood that evaporation of intercepted snow explains' the increased accumulation in dearings. Snow held on branches presents a huge extension of surface area exposed to moving air, compared to the snow surfac.e in the dearing. Intensive snowboard measureme·nts reported by ""heeler (in press) for the 1985-86 winte.r, demonstrate that accumulation differences between dearing and fore.st (1) usually occur during storms, not between storms, and (2) are inversely relate.d to wind speed during the storm. Both re.sults, but especially the latter, argue against aerodynamic redistribution as the main cause of the difference. The electronic system described here is a step toward the detailed studies of the distribution and evaporation of snowfall in forest canopies and clearings called for by Goodell in 1963. This paper presents a method of counting precipitating snow crystals, and shows example results from a cut block on the Fraser Experimental Forest. Study Site The cut block, 80m wide in a stand of mature spruce and lodgepole pine with an understory of subalpine fir, extends 100m down a north-facing slope (40%) draining into West St. Loui.s Creek, in the Fraser Experimental Forest (fig. 1). The block is near Short Cre.ek, in the center of Section 8, T2S, R76W, at 2925m elevation (9600ft), 106°54' west longitude, 39"52'30" north latitude. Wind during storms is most often from the west to northwest at this site. Troendle designed the block and erected towers for these experiments, with the assistance of ]\.lan11al H. Martinez, who also constructed the tower wiring harnesses and placed the cables between the 11-1ydrologist and Forestry Technician, respectively, with the 110cky Mountain Forest and Range Experiment Station, 222 South 22nd Street, Laramie, Wyoming, 82070·5299, in cooperation with the University of Wyoming. Station headquarters is in Fort Collins, in cooperation with Colorado State University. 227 MAST #3 DOWNWIND MAST #2 CLEARING MAST #1 UPWIND GENERATOR ~WIND TRAILER Figure 1.--The experimental site on West St. louis Creek Includes a cut block In a mixed stand of spruce, fir, and lodgepole 1,lne. This clearing Is 80m wide and extends 100m down a north-facing 40% slope. Towers are located (1) upwind, (2) center, and (3) downwind of the clearing, with 85m separating towers 1 and 2. Counting Snowflakes towers and the trailer. A 27m tower supports instruments in the center of the dearing, 40m east from the upwind edge. In the upwind forest, 85m from the clearing tower, a 34m tower extends about 16m above the average canopy height of 18m. A third tower in the forest downwind of the dearing was not used in initial experiments with this system. (All three towers carried triaxial anemometers at two levels as part of another study by David ~1iller.) For the first tests, six sensors were uniformly spaced 3m (10ft) apart between 15 and 30m on the upwind mast during several storms. The lowest two sensors were below the average canopy height. AU sensors were then deployed on the clearing tower, again at the same spacing, between 11 and 26m above the snow surface, during two storms. Finally, three sensors measured snowfaU at the highest (#:1), lowest (ll6), and #4 position on both towers, allowing coniparison of simultaneous counts in the forest and clearing. The system (fig. 2) consists of the sensors mounted on towers, wiring harnesses on each tower to provide signal and power interconnections, cables from each tower to a small instrument trailer below the dearing, counting circuits that sum each sensor's signals, and the desk-top computer (PC). A propane.-driven generator provides satisfactory electric power, since the system operates only during events when an observer is at the site. The snow sensor, called a snow particle counter (SPC), is a device developed to measure the number and size of particles moving in blizzards (Schmidt 1977). Two phototransistors sense shadows cast by particles passing through a light beam (fig. 3), producing voltage pulses that are amplified at the sensor and sent to counting circuits. Pulse amplitude is related to the size of the particle's shadow. (For these initial 228 experiments, the system does not extract the information on particle size, however.) The microprocessor syste.m (fig. 2) passes counts from runs, of 1 to 10 min duration, to the computer for printing and storage on di.sk. Using an internal analog-to-digital converter, the computer also monitors wind spee.d and direction from an anemometer and vane mounted at 10m on the clearing tower. To assure comparable sensitivity, each SPC is calibrated by spinning a wire through the beam and adjusting amplification for a standard output, measured as peak-to-peak pulse amplitude on an oscilloscope. This was accomplished before and after each day's experiment for the first few events, until experience showed such frequent calibrations were unnecessary. After that, calibrations were checked when some· change was made in the setup, suc.h as nu;ving sensors between towers. (l\filler equippe.d each tower with a safety rope and halyard system, which greatly fadlitated calibration of the SPC's.) Example Results Although the objective of initial experime.nts was only to test the measurement technique, transfer from our laboratory to Dr. Troendle's study site proceeded so smoothly that he was able to test two hypotheses concerning the snow ac.c.umulation problem during l\farch, 1987. Details will be reported elsewhere, but the hypotheses were: (1) There is no significant differe.nce i.n particle counts between levels on a tower, and (2) The.re. is no si.gnificant difference between average counts at each tower. TOWER 2 TOWER 1 #1 #3 #2 SENSOR POSITIONS #4 #5 #5 #6 #6 c: 01 downwind Figure 3.--The snow particle counter (SPC) senses the shadow of particles passing through the light beam, producing amplified voltage pulses. With two windows, estimates of particle speed are possible (from Schmidt 1977). Figures 4a and 4b show typical exam pIes of counts when all sensors were on one tower. Counts were normalized by the mean count of all sensors for each run, and heights we·re normalized by the midpoint and spacing of the sensor array. Figure 4c is a comparison of c.ounts during a run with three sensors at each tower. We found no large di.fferences i.n average counts between towers. Although designed to measure the smaller pa.rticles and greater frequency of drifting in blizzards, the SPC's provide.d useful and a.pparently consistent mea.sures of snowfaH under light winds in a forest canopy. If these preliminary results withstand tests for statistical significance, it appears that particle count usually increases with height both in the clearing and above the c.anopy (although the opposite gradient was occasionally observed). Average counts seem to be about the same at each tower, however. The next question is, "Are particle sizes similar?"-that is, do these counts represent the same mass flu."t. We are adding electronics to determine size distributions for expe.riments during the 1987-88 winter. To explain the decrease in count within the forest seems simple.-- interception. Yet a similar gradie.nt of partide. numbers appears in the dearing measurements. Does this reflect an aerodynamic. effect? Anemometers at each SPC location will heJp esti.mate particle trajectories in upcomi.ng experiments with this system. #3 #4 '0 'jj; Plans #1 #2 & o ~f--L----""~~:':':":="'-­ SHIELDED CABLES Literature Citeci 1_______________________________________ _ Goodell, B. C.1959. Management of forest stands in Western United States to influence the flow of snow-fed streams. In: Symppsium of Hannoversch-Munden, Publication No. 48 of the International Assodation of Sdentific Hydrology, Gentbrugge, Belgium. 1: 49-58. Figure 2.--Slgnals fl'C)m ea(:h SPC on the t()VI(~rs am summed and transferred to the computer by a microprocessor system. An ana.log-to-digltal converter in the compute,' measures voltages from wind speed and direction sensors at the 10-m height on tower 2, in the clearing. 229 2.5 2.5 UPWIND FOREST 11 MARCH 1987 RUN 14 MIDPOINT= 22.9m SPACING= 3. 3m Q. l.:) 1.5 Z U l.:) U '- CL 0.5 (J) + UJ ~ z ....... 0 CL 0 ....... -0.5 + 0.5 ~ 1. ~ 0 CL (COUNT -MEAN) 0 ....... MEAN a (COUNT -MEAN) -0.5 MEAN ::E I l- I I w 'z l- ....... ~ I-i ::E I l.:) 16 MARCH 1987 RUN 11 MIDPOINT= 18.9m SPACING= 3. 3m <: <: CL (J) 1.5 z ....... ~ b. CLEARING -1. 5 l.:) + I-i MEAN COUNT= 74 w -1. 5 MEAN CDUNT= 85 3 3 -2.5 -2.5 2.5 .y SIMULTANEOUS UPWIND o CLEARING 20 MARCH 1987 RUN 3 c. + Cl 1.5 z 1-1 Figure IJ.-Example plots of particle counts during 5~mln runs with six sensors at (a) towel' 1 (upwind) and (b) tower 2 (clearing). Three sensors at each towel' gave the counts In (e). Both count and height are normalized by the respective means. u <: CL (J) ',--,. 0. 5 1.0 l- z 0 CL 0 I I I I (COUNT -HEAN) -0.5 ----------------- MEAN ::E I l- I Cl 1-1 w / -1. 5 MEAN COUNT= 763 / 3 -2.5 ~) Tabler, Ronald 0.1975. Estimating the. transport and evaporation of blowing snow. liz: Snow Management on the Great Plains: Proceeding of the symposium; 1975 July 29; Bi.smarck ND. Publication No. 73. Research Committee of the Great Plains Agricultural Council. Agricultural Experiment Station. Unive.rsity of Nebraska, Lincoln. 85104. Goodell, B. C. 1963. A reappraisal of precipitation interception by plants and attendant water loss. Journal of Soil and Water Conservation. 18(6): 231-324. Hoover, Marvin D. and Charles F. Leaf 1967. Process and significance of interception in Colorado subalpine forest. In: Forest Hydrology: Proceedings of an International Symposium; Vol. E. Soper and H. 'AT. Lull (eds.). Pergamon Press, New York. 213-223. Tabler, Ronald D., and R. A. Schmidt. 1972. Weather conditi.ons that determine snow transport distances at a site in Wyoming. In: The role of snow and ice in hydrology: Proceedi.ngs of the Banff Symposia; 1972 Septe.mber; Banff, Alberta, Canada. UNESCO/'Vl\fO/IAHS. Vol. 1. 118-127. Troendle, C. A. and R. M. King. 1985. The effect of timber harvest on the Fool Creek watershed, 30 years later. Water Resources Research. 21(12): 1915-1922. Schmidt, R. A. 1972. Sublimation of wind-transported snow-a model. Research Paper RM-90. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky l\1ountain Fore·st and Range Experiment Station. Fort Collins, CO. 24 p. Schmidt, R. A. 1977. A system that measures blowing snow. Research Paper RM-194. U.S. Department of Agriculture., Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Forest and Range Experiment Station. Fort Collins, CO. 80 p. 'ATheeler, Kent. (in press). Interception and redistribution of snow in a subalpine forest on a storm-by-storm basis. In: 55th Annual Western Snow Conference: Proceedings; 1987 April. Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada. Schmidt, R. A. 1982. Vertical profiles of wind spee.d, snow concentration, and humidity in blowing snow. Boundary Layer l\feteorology. 23: 223-246. 230