J S P

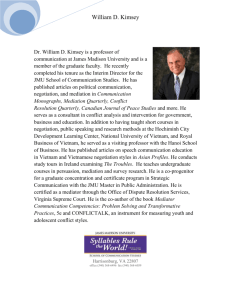

advertisement