Monetary Policy and Real Borrowing Costs at the Zero Lower Bound

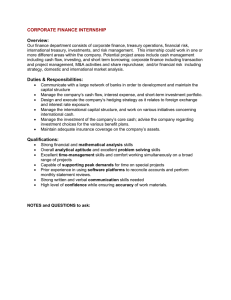

advertisement