Advance copy

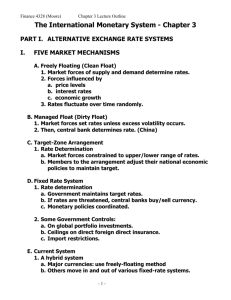

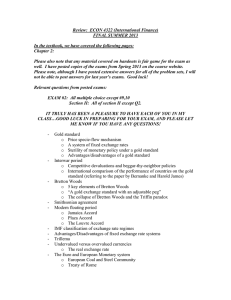

advertisement