HEALTH & SCIENCE American Medical News March 19, 2007

advertisement

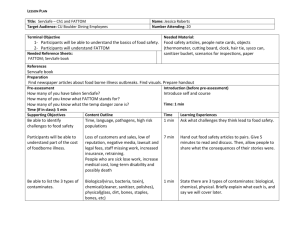

HEALTH & SCIENCE American Medical News March 19, 2007 Tackling tainted food: A lot can go wrong -- at any step along the way Diagnosing a foodborne illness is straightforward. Determining where and when the pathogen started may be more challenging. By Victoria Stagg Elliott, AMNews staff. March 19, 2007. Last fall, Dr. Samiya Razzaq, a pediatrician at Arkansas Children's Hospital in Little Rock, witnessed the result of gaps in the nation's food safety controls. Three young children were sick enough to be transferred to her institution because of something they ate. Another 40 from the same day care center also were ill, although they did not have to be hospitalized. "The whole food safety system is fragile," said Dr. Razzaq, who also teaches at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences. "One little mistake from somewhere and it's a major epidemic." The good news is that these patients recovered. But the cause of this illness cluster has not been confirmed, and Dr. Razzaq suspects it may have been part of the large national outbreak of Escherichia coli O157:H7 reported in September 2006 and associated with raw, bagged, pre-washed spinach. At least 204 cases were confirmed across the country, including three deaths. Foodborne illnesses have made headlines in the past six months with stories ranging from Salmonella-contaminated peanut butter to Clostridium botulinumtainted baby food. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimate that 76 million illnesses annually can be blamed on foodborne pathogens. And each year, 325,000 people are hospitalized; 5,000 do not survive. Ironically, it is produce -- usually considered to be among the healthiest of foods - that has been associated with much of the recent harm. The latest report from the CDC's Foodborne Diseases Active Surveillance Network says food-related illnesses have declined over the past decade, and many experts say the food supply is more safe than ever. But produce seems to be responsible for a growing percentage of these incidents, with bagged salad blamed most often. According to the Center for Science in the Public Interest, salads are the culprit in 28% of produce-related outbreaks. "We live in a microbial world. If something has crawled or slithered or flown over that field and defecated, there's really little we can do to decontaminate that piece of produce," said Sam Beattie, PhD, assistant professor in food science and human nutrition at Iowa State University in Ames. To be fair, detection of recent widespread outbreaks in part can be attributed to improved public health technology and industry trace-back systems. The development of pulsed field gel electrophoresis means that bacteria can be distinguished at the DNA level, and the establishment of CDC's PulseNet just over a decade ago allows public health and food regulatory agency laboratories to match up these bacterial "fingerprints." "A patient in Ohio, somebody else in Florida, someone else in Long Island might have gone unrecognized before," said Marguerite Neill, MD, associate professor of medicine at Brown Medical School and an infectious disease physician at Memorial Hospital of Rhode Island in Pawtucket. But factors other than detection bias are probably at work, too, experts say. For instance, E. coli O157:H7, which was discovered only decades ago, has proven to be more virulent than many other pathogens. Washing will reduce its presence, but even nearly undetectable amounts are dangerous. Changes in how food is produced and eaten also may play a role. Food is more likely to be mass-produced and distributed widely rather than being grown and eaten locally, making contamination during the production process a national, even international, problem. The most recent spinach outbreak hit people in 26 states and Canada. "When your food came from the farm down the street, people got sick, but the number of people made ill was small," said Bennett Lorber, MD, Thomas M. Durant Professor of Medicine in the infectious diseases section at Temple University School of Medicine in Philadelphia. "Now we have immense food producers, producing incredible volumes of food, and it's distributed all over country. If there's a contamination problem, there's the potential for many, many people to be sick." Consumers also are eating more produce, particularly if it has been cut and washed before being packaged. According to the U.S. Dept. of Agriculture, per capita consumption of fresh spinach in 1980 was less than half a pound per person. It increased to more than a pound and a half in 2003. Much of this growth is due to increases in sales of triple-washed, ready-to-eat bagged spinach. While such products make it easier to eat these generally healthy foods, it also appears to present more possibilities for contamination as spinach makes its way from the farm to the dinner table. "Not a controlled environment" The leading candidate for last fall's spinach-related outbreak is feces from cattle at bordering ranches or from wild pigs who wandered through fields, but the irrigation water or the wash used in processing could have been tainted. The problem could have been fertilizer. Cutting the vegetable in the fields may make a ripe environment for bacteria to flourish. Those who picked, processed and packaged it may not have had good hygiene. "A farm is outside. It's not a controlled environment," said Don Schaffner, PhD, a spokesman for the Institute of Food Technologists, an international nonprofit of 22,000 food scientists. "You can't control the rainfall. You can train people to wash their hands, but cows and pigs cannot be as easily trained. And heaven help us if the problem comes from birds." Packaging may be conducive to bacterial growth, although this is unproven. The product may have been improperly stored in transport, the grocery store or the consumer's home. Once the vegetable is out of the package, it could be mishandled. Although farming and processing issues are getting attention right now, consumer mishandling remains the most common cause of foodborne illness. "Somebody makes some hamburgers. Then they use the same cutting board and cut up some spinach for spinach salad, and there's cross-contamination," said Jeffrey T. LeJeune, DVM, PhD, who teaches in the food animal health research program at Ohio State University. While the actual reason for last fall's outbreak is unclear, government and industry stakeholders are taking action. In January, the large fresh-cut salad producer Fresh Express, whose products were not associated with the illness, said it would provide $2 million for research leading to strategies that would prevent E. coli contamination. Also, last month, more than 90% of companies in this industry signed the California Leafy Greens Marketing Agreement requiring signatories to follow guidelines governing irrigation water quality, purity and timing of fertilizer, harvesting equipment cleaning, and farm worker behavior. "Food safety is a sacred trust between the people in our industry and the public," said Tom Nassif, president and CEO of Western Growers, an agriculture trade group in Irvine, Calif. "We take that responsibility extremely seriously." Meanwhile, the Food and Drug Administration added spinach to its Lettuce Safety Initiative and will hold a public meeting this year on foodborne illness associated with greens. The agency also will consider if more guidance or regulation is necessary or if irradiation of these products should be allowed. The USDA is funding research to assess the presence of E. coli to determine its sources and look for strategies to reduce it. The Government Accountability Office called transforming food safety a high-risk issue in January and wants the structure of the system, currently run by 15 federal agencies, to be reconsidered. "There ought to be a government-wide approach to food safety," said Lisa Shames, GAO acting director of food and agriculture issues. "It's not that food is unsafe. It's just that the system is fragmented." Can physicians do more? Food safety issues also maintain a high profile among physician concerns. The American Medical Association published Diagnosis and Management of Foodborne Illnesses: A Primer for Physicians and Other Health Care Professionals, in conjunction with the American Nurses Assn., the CDC, the FDA's Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition and the USDA's Food Safety and Inspection Service in April 2004. But food safety experts want more. Those working in this area want physicians to step up testing to determine exactly what is causing a patient's illness to make outbreak detection easier. Knowing that can affect treatment decisions because, in the case of E. coli O157:H7, evidence suggests that antibiotic use can make things worse. "A lot of time physicians will tell people, 'Oh, it's food poisoning.' But they'll never order a stool culture," said Dr. Schaffner of the food technologists group. "I know physicians are limited by insurance, but it would really be wonderful for physicians to work with us more closely." Physicians say this is not always practical. Millions may be affected by foodborne illness, but only a fraction are sick enough to see a doctor. Because there is no rapid in-office test, an even smaller percentage will still be sick when results come in. For example, Richard Roberts, MD, a family physician in Belleville, Wis., treated a 70-year-old man in August 2006. The man had severe diarrhea and may have been a part of the spinach outbreak. He collected stool cultures, because the man's age put him at greater risk for severe illness. The test results came back days later as positive for E. coli O157:H7. By then, though, the man was well. "The problem with getting cultures most of the time is that by the time you get the results back the person is better. Then you feel like you've wasted money," said Dr. Roberts, former president of the American Academy of Family Physicians. "You give me a test that I can do on the spot at a reasonable price and have the results here in the clinic. I'll do that." � Recognize that a foodborne contaminant may be making a patient sick. � Realize that many illnesses resulting from food consumption, although not all, have gastrointestinal symptoms. � Obtain stool cultures as appropriate. � Request testing for some pathogens as necessary. � Consider the possibility of intentional contamination. � Report suspect cases to public health officials. � Discuss with patients ways to prevent food-related disease. � Acknowledge that the young, old, pregnant and those with compromised immune systems face greater risks from foodborne illnesses. � Appreciate that any patient with a foodborne illness may represent the first clue to a more widespread outbreak. Source: Diagnosis and management of foodborne illnesses: A primer for physicians and other health care professionals, February 2004