Category taken-for-grantedness as a strategic opportunity:

advertisement

Category taken-for-grantedness as a strategic opportunity:

The case of light cigarettes, 1964-1993

Greta Hsu

Graduate School of Management

University of California, Davis

Davis, California 95616, USA

grhsu@ucdavis.edu

Stine Grodal

Boston University School of Management

595 Commonwealth Ave., Room 639-A

Boston, MA 02215, USA

!grodal@bu.edu

Abstract

Theories within organizational and economic sociology that center on market categories

often equate taken-for-grantedness with increased constraint on the features of category

members. In contrast, we develop a novel perspective that considers how market

participants’ changing category-related attributions decrease their scrutiny of category

offerings, opening up strategic opportunities for firms. We further argue that whether or

not producers should be expected to take advantage of these opportunities depends on the

extent to which they are incentivized to do so. We use the case of the light cigarette

category to test this thesis. We argue and find evidence that increasing taken-forgrantedness of the light cigarette category created greater opportunity for tobacco firms to

strategically manipulate category features.

!

In the mid-1960’s, a new cigarette type emerged in the U.S. designed to address increasing

concerns among smokers about the relationship between cigarette smoking and lung cancer.

Brands marketed under this new type touted significantly reduced deliveries of tar and nicotine

compared to existing brands on the market, which subsequently became labeled “full flavor”

brands. Producers of early “light” category entrants emphasized a variety of innovative features,

including technologically advanced filters, new tobacco blends, and enhanced paper porosity, all

designed to reduce tar and nicotine deliveries.

Over the next few decades, attention to the negative health-related consequences of

smoking mounted (Kluger, 1997; Brandt, 2007). Public focus was mainly directed at tar and

nicotine as the components commonly associated with the harms of cigarette smoking, and

information about brands’ tar and nicotine content became publicized and widely available in the

U.S. (Glantz et al., 1996). As a result, producers decreased deliveries of both components

substantially among full flavor cigarettes from 1964 to 1993. Yet, a very different pattern

emerged within the light cigarette category. Average tar deliveries for cigarettes marketed as

light increased 7% (from 9.6 mg in 1964 to 10.3 mg tar in 1993), while nicotine deliveries

increased 74% (from 0.46 mg to 0.80 mg). What led to this distinct pattern among light

cigarettes—a market category specifically defined around low levels of tar and nicotine?

One explanation points to the forces of market competition. Light cigarettes may have

increased tar and nicotine deliveries because, as the category developed, competition heated up

among light cigarettes brands, pushing firms to stake out higher, previously unoccupied positions

along the tar/nicotine spectrums. Relatedly, the addictive nature of cigarettes may have been a

driving force. Consumers may have preferred safer alternatives to full flavor cigarettes, but

continued to crave a strong flavor and nicotine-derived “kick.” Tobacco firms accordingly

!

"!

increased tar and nicotine deliveries of light cigarettes in an effort to meet consumer demand.

Historical records indicate that such demand- and competition-driven dynamics certainly played

a role in this context.

Yet, what is missing from these accounts is an adequate explanation for why an industry

that was heavily scrutinized by regulators, anti-tobacco activists, and consumers could

significantly increase the deliveries of highly salient components such as tar and nicotine without

negative repercussion. In other words, the interesting question posed by this case is not what led

tobacco firms to increase tar and nicotine deliveries among cigarettes marketed as light, but what

enabled firms to do so in the midst of intense attention towards these core product

characteristics? Why weren’t these increases censured for a market category defined around low

deliveries of tar and nicotine? The answers to these questions require consideration of how

market actors perceived and evaluated brands claiming membership in the light cigarette

category. More broadly, they relate to fundamental issues within economic and cognitive

sociology about the way social categories influence perception (Durkheim, 1912; Douglas, 1986;

Zerubavel, 1997; DiMaggio, 1997) and how market producers are both subject to and influencers

of evolving categorical expectations (e.g. Zuckerman, 1999; Lounsbury and Glynn, 2001; Rao,

Monin, and Durand, 2005; Hsu, Hannan, and Koçak, 2009; Kennedy, 2008).

In this study, we use evidence from tobacco firm internal documents to gain insight into

how producers attempted to both understand and influence the way consumers perceived the

light cigarette category. Such records call into question the generalizability of existing

perspectives that equate taken-for-grantedness with increasing constraint on the features of

category members (DiMaggio and Powell, 1983; Ruef and Patterson, 2009; Negro, Hannan, and

Rao, 2010; Kovács and Hannan, 2010). Those studies find that, as categorical understandings

!

#!

becomes increasingly taken-for-granted, market participants exact stronger penalties on

producers who explicitly deviate from a category’s expected features. As a result, producers

become more constrained in their choice of features.

In contrast, the grounded view provided by our historical investigation suggests one

important way in which the constraint imposed on producers’ choice of features lessens rather

than increases as categorical understandings evolve. We find evidence that the extent to which

consumers scrutinized the actual features of light cigarette category claimants decreased as their

category understandings become increasingly taken-for-granted. This is consistent with

theoretical work proposing that, as their category understandings develop, people increasingly

rely on category schemas as cognitive shortcuts to infer rather than directly perceive members’

features (DiMaggio, 1997; Hannan, Pólos, and Carroll, 2007; Hsu, Hannan, and Pólos, 2011).

Working from this insight, we develop a novel perspective that considers how market

participants’ changing category-related attributions decrease their scrutiny of category offerings,

opening up strategic opportunities for firms.

We further argue that whether or not producers should be expected to take advantage of

the opportunities presented by market participants’ increasing reliance on category shortcuts

depends on the extent to which they are incentivized to do so. For example, producers may face

cost-based incentives, such as when adopting category-relevant features entails significant

production costs or difficulty (e.g. “organic” versus conventional produce). Producers who can

successfully claim membership while using less expensive category-inconsistent methods may

benefit from enhanced profitability.

We find particularly interesting the incentives presented by a class of market categories

for which consumers are conflicted in their evaluations of category members along category-

!

$!

relevant dimensions. Such categories have not to our knowledge, received attention in

sociological literature on market categorization. Researchers have typically classified categories

as either positively valenced, where greater fit with category expectations leads to greater appeal,

or negatively valenced categories (e.g., “sweatshop”), where greater fit leads to more negative

valuations (Hannan et al., 2007). Yet, consumers experience conflict in their evaluations for a

number of market categories. For example, many consumers find ethical products such as

fair labor clothing appealing due to their socially responsible nature, but simultaneously assume

such products to be inferior in quality or design (Ehrich and Irwin 2005). In the light cigarette

case, many smokers were both attracted to the health benefits of light cigarettes and turned off by

their presumed weak, unsatisfying taste (e.g. Brand, Gruber, and Co., 1976). As we explain

below, such conflict presents strong incentives for producers to relax their fit with categoryrelevant features in order to increase the overall appeal of their offerings. This makes producers

particularly likely to capitalize on the opportunities presented by the changing patterns of

perception that accompany category taken-for-grantedness.

We begin with a brief overview of the evolution of the light cigarette category in the

U.S., 1964 – 1993. We then examine evidence retrieved from the Legacy Tobacco Documents

Library (http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu), a database maintaining internal tobacco firm documents

made public through litigation between 46 U.S. States and the major tobacco companies in 1994,

to gain insight into the firms’ perspectives and actions with regards to this category over the

period studied. We integrate these insights with related theorization on category schemas and

their evolution to form hypotheses regarding the impact of changing taken-for-grantedness on

producers’ strategic positioning of their light cigarette brands. We test our hypotheses by

examining cigarette brands sold in the U.S. from 1964 to 1993. We conclude by considering

!

%!

how our results clarify basic dynamics underlying category taken-for-grantedness and contribute

to multiple subfields within sociology that use categories as a tool for understanding

organizational-environmental relationships, including the sociology of markets, organizational

ecology, institutional theory, cognitive sociology, and cultural sociology (see Baumann, Dowd,

and Janssen, 2008; Cerulo, 2010; Negro, Hsu, and Koçak, 2010 for reviews).

The Evolution of Light Cigarettes

The seeds of the light cigarette category were planted during the early-to-mid 1950s,

when several landmark studies led to widespread support among physicians, scientists, and

public health professionals for a causal relationship between cigarette smoking and lung cancer

(Brecher et al., 1963; Kluger, 1997). Prior to this, health-related concerns with cigarettes

focused mainly on minor issues such as throat irritation (Kluger, 1997), and moderate levels of

smoking were generally considered acceptable by physicians (Brandt, 2007; Glantz et al., 1996).

High-profile media articles reporting cigarettes’ link to cancer and comparing the tar and

nicotine deliveries of major cigarette brands generated concerns among the broader public in the

1950s (Ippolito et al., 1979). In response, tobacco companies developed and introduced new

“filtered” brands marketed as healthier than traditional cigarettes (Kluger, 1997). During the

latter part of the 1950s, the marketplace was flooded with unsubstantiated advertising claims

about the efficiency of brands’ filters in reducing tar and nicotine (Pollay and Dewhirst, 2002;

Glantz et al., 1996). This frenzy spiraled until 1960, when cigarette manufacturers met with the

FTC in closed-door negotiations and voluntarily agreed to refrain from making any claims

regarding filter effectiveness in their promotions (Brecher et al., 1963; McAuliffe, 1988).

!

&!

Over the next decade, public awareness of the hazards of smoking increased. Dr. Luther

L. Terry, the U.S. Surgeon General, played a pivotal role through his widely publicized 1964

report which concluded smoking to be a cause of lung cancer (Brandt, 2007). Later that same

year, a Gallup poll survey found that 62% of U.S. adults believed smoking to be one of the

causes of lung cancer, compared to 39% in 1954 (The Gallup Organization, 1964).

Regulatory pressures on cigarette producers also increased. In 1965, the U.S. Congress

enacted the Original Federal Cigarette Labeling and Advertising Act requiring all cigarette

packages to carry messages linking smoking and health (Brandt, 2007). In 1966, the FTC

reversed its policy discouraging tar and nicotine statements in advertisements, and in 1967 began

testing and publishing lists of cigarette brands’ tar and nicotine deliveries (FTC news release,

1967). In 1971, the FTC reached an agreement with tobacco firms whereby all cigarette ads

would explicitly state brands’ tar and nicotine deliveries (Ippolito et al., 1979). The same year,

health warnings also became required on all cigarette print ads and Congressional ban on

television broadcast cigarette ads went into effect (McAuliffe, 1988).

In the midst of these mounting pressures, tobacco firms turned once again to product

innovation to reassure and retain health-concerned smokers. The mid-1960s marked the advent

of a new breed of cigarettes marketed as “low in tar and nicotine”. Early entrants were brands

belonging to new “freestanding” low tar/nicotine brand families such as True and Carlton. The

names given to these brands often implied “state-of-the-art technology and/or a virtuous product,

e.g. Life, Merit, Now, True, or Vantage” (Pollay and Dewhirst, 2001: 232). These early entrants

were followed in the early-to-mid 1970s by low tar/nicotine extension brands of existing full

flavor brand families such as Marlboro Lights and Winston Lights. Our data show that, by 1975,

all of the major tobacco manufacturers (American Tobacco Co.; Brown & Williamson Tobacco

!

'!

Corp.; Liggett Group, Inc.; Lorillard, Inc.; Philip Morris, Inc.; & R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Co.,

Inc) produced both freestanding and extension light brands for the U.S. market.

Manufacturers fought to establish footholds in this growing category by devoting a

disproportionate amount of their total advertising budgets to light brands (Pollay and Dewhirst,

2001). Growth was also fueled by continual increases in the proportion of Americans who

believed smoking to be a cause of lung cancer (The Gallup Organization, 1981) as well as by

tobacco firms’ efforts to court influential “political and scientific friends” who could credibly

endorse light cigarettes as a lowered health risk (e.g. Wells, 1982).

As Figure 1 shows, the rate of increase in light sales was relatively gradual until the mid1970s, when sales began a sharp increase. In 1976, 81 billion units were sold; by 1985, this had

increased to 320 billion units (source: Annual Maxwell Reports). Over this same time period,

sales of full flavor cigarettes declined significantly, indicating a general shift of many new and

existing smokers towards the light cigarette category as well as increasing public awareness of

the negative health-related consequences of smoking (Brandt, 2007). After 1985, light cigarettes

also joined this downwards trend with a gradual decline in sales.

In the next section, we integrate historical evidence with theoretical insights to consider

how the light cigarette category emerged to cue health-concerned smokers as to which types of

cigarettes they could safely consume. Instead of attending to individual brands’ tar and nicotine

deliveries, consumers came to rely on the light cigarette category label as a cognitive shortcut

denoting health and safety.

!

(!

Evolving Perceptions of the Light Cigarette Category

Extant theory holds that market actors during the early period of category emergence tend

to lack a clear category schema. They may perceive some similarities among a set of offerings

and even regard them as members of a common set, but understandings of what determines

membership in that set are generally vague (Hannan et al., 2007). As actors compare the

characteristics of claimants to the newly emerging category with one another, they begin to form

category beliefs based on perceived similarities. These patterns are shaped by factors such as

actors’ goals and existing knowledge (Murphy, 2002). For example, prior knowledge about a

market domain channels actors’ perceptions towards particular feature dimensions thought to be

relevant to category membership (Rehder, 2003; Durand and Paolella, 2012). In line with this,

studies suggest that actors compare their newly forming schema with schemas for related

preexisting categories (Rosa et al., 1999; Pontikes, 2013) to inform their understandings of

whether offerings are the “same or different” (Weick, Sutcliffe, and Obstfeld, 2005: 414; Weick,

1995). Market actors’ goals can also influence the development of new categories (Barsalou,

1983; Durand and Paolella, 2012; Etzion 2013), as the existence of specific goals (such as

consuming a cigarette that is safer) focuses actors’ attention on dimensions relevant to those

aims.

These accounts aptly characterize the early process of light category development from

the perspective of tobacco firms. Early on, there was considerably ambiguity about the light

category. Although the earliest members of the light cigarette category entered the U.S. market

in 1964, it took several years for firms to begin to recognize the emergence of a distinct type.

Firms continued to demarcate the cigarette market into filtered versus non-filtered cigarettes,

with what now are regarded as the earliest light category members slotted into the filtered

!

)!

category (e.g. Foote, Cone & Belding Advertising, Inc., 1966). The growing importance of

health-related goals to smokers, and evolving understandings of tar and nicotine as harmful

components of cigarette smoke, increased the salience of these particular feature dimensions.

As a result, early perceptions of light cigarettes largely focused on individual brands’

rankings along tar and nicotine deliveries. For example, a 1966 Kent sales analysis for Lorillard

Co. described the cigarette market as a spectrum with non-filtered, high tar and nicotine brands

on one end, and “high filtration” brands on the other (Grey Marketing and Research Department,

1966). Philip Morris, which conducted monthly analyses of the tar and nicotine delivery of

competitors’ cigarettes, started grouping brands under the term “Low Delivery Cigarettes” in

1967 based on tar and nicotine deliveries (Ikeda, Sanderson, and Wickham, 1967).

When a category is emerging and ambiguity is high, different market actors often vary in

who they regard as category members and what their proposed criteria for membership are (Rosa

et al., 1999; Granqvist et al., 2013). Evidence of this could be seen during the early 1970s, as

firm insiders actively tried to figure out who the members of the light category were. A 1973

Brown and Williamson report summarizes the company’s efforts to study which brands

consumers regarded as “hi-fi” and how these diverged from what the company considered to be

members of the high filtration category (Brown and Williamson, 1973). Similarly, a 1973 Philip

Morris report (Eichorn and Tindall, 1973) notes that “[t]he low delivery segment is not well

defined. If other people were asked to list brands in the low delivery segment they would

probably choose other brands.” During this time, a number of different labels for this emerging

category could be seen in different companies’ internal documents, including “high-filtration”,

“super-fi”, “low delivery”, “low tar and nicotine”, “light,” and “health” cigarettes.

!

*!

The absence of formal standards regarding which brands could be marketed under labels

indicating low deliveries contributed to this ambiguity. Cigarettes advertising referencing tar or

nicotine deliveries were subject to FTC testing and public disclosure of delivery numbers (FTC

press release, 1967); there were no regulations, however, on the maximum deliveries for brands

claiming to be members of the light cigarette category.

Research suggests that early category producers expend considerable effort sensegiving

about their proposed category and its collective membership in order to both influence market

participants’ category understandings and gain their attention and resources (Aldrich and Fiol,

1994; Lounsbury and Glynn, 2001; Kennedy, 2008; Santos and Eisenhardt, 2009; Navis and

Glynn, 2010; Dobrev and Gotsopoulos, 2010; Khaire and Wadhwani, 2010). Such explication is

a central component in the creation of category taken-for-grantedness (Colyvas and Powell,

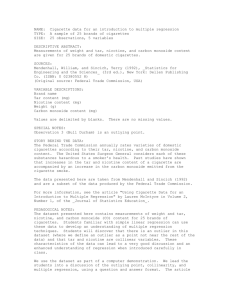

2006). In the cigarette case, product advertisements were a key medium through which

producers established light cigarettes as a distinct, safer cigarette type. Producers marketed early

light brands through ads that emphasized their low tar and nicotine deliveries and explicitly

described scientific breakthroughs in the technology and methods used to produce these (Pollay

and Dewhirst, 2002). As noted in an internal Philip Morris document, a key aim was to convey

“scientific substance and validity…The ads were written in a journalistic, repertorial [sic] style to

be precise, pointed, and absolutely believable.” (Wakeham, 1977). Figure 2, a 1964 print ad for

the light brand Carlton, provides an example of this, referencing test samples analyzed by “an

independent research laboratory” and technological advancements such as “high porosity paper”

and a filter with “precision air vents”.

A qualitative examination of light cigarette ads over the study period (see the Appendix

for sampling and coding details) reveals systematic changes in the explicitness of discourse

!

"+!

establishing the scientific basis for light cigarettes. The solid line in Figure 3 shows the

proportion of light cigarette ads that explicitly described scientific techniques designed to reduce

tar and nicotine deliveries and/or explanations of key components within cigarettes such as tar,

nicotine, and carbon monoxide. This reflects the extent to which firms explicitly drew attention

and explained to consumers the features that enabled low tar and nicotine deliveries and

distinguished light from full flavor cigarettes. Prior to 1970, almost all cigarette ads included

explicit scientific discourse. There was a sharp drop over the first half of the 1970s, a slight

leveling off, and then another sharp drop during the late 1970s and early 1980s. By 1985, only

approximately 1 in 10 ads included any reference to scientific techniques or methods.

Firms also enhance the taken-for-granted status of a category through references to

within-category competitors. Co-mentions in public stories (such as press releases and product

advertisements) render similarities between category members salient to market participants,

helping to clearly define an emerging category in the public’s eyes (Kennedy, 2008). In Figure

3, the dotted line indicates the proportion of light cigarette ads with prominent references to

competitor light brands. There was a sharp increase from 1964 to 1970 in the proportion of ads

referencing competitor brands. This coincides with our earlier observation of a several year lag

between the first cigarettes marketed as light and producers’ realization that a new category type

was emerging. Over the 1970s, the proportion of ads mentioning competitors hovered in the 0.5

range, then sharply declined over the 1980s. By that period, studies suggest references to rival

brands became less advantageous due to higher levels of taken-for-grantedness for the category

as a whole (Kennedy, 2008; Lounsbury and Glynn, 2001; Navis and Glynn, 2010).

To measure the evolving taken-for-grantedness of the light cigarette category, we

sampled media accounts from 1964 – 1993 that included references to the light cigarette

!

""!

category. When ambiguity over a category is high, category-related discussions must include

explicit definition and explanation of the category and what it represents. A decrease in such

explanatory discourse provides a visible marker of category taken-for-grantedness (see Colyvas

and Powell, 2006). Accordingly, we coded media accounts for the extent to which references to

light cigarettes included explicit definition of the category’s features and membership criteria.1

This consists of, among other things, the specific techniques and raw materials used to produce

light cigarettes, the health effects associated with a reduction in tar/nicotine deliveries, and

results from FTC testing of brands’ tar/nicotine deliveries.

Figure 4 shows the trend in our measure of the extensiveness of light cigarette category

explanations in media accounts. As this figure shows, there was a gradual decline in this

measure from 1964 to 1970, sharper declines over the 1970s, followed again by a period of more

gradual decline over the 1980s. Together with the sales data (which indicated a sharp increase in

light cigarette sales starting in the mid-1970s), this suggests that light cigarette taken-forgrantedness developed most noticeably over the 1970s, although development continued to be

seen over the 1980s.

Strategic Positioning of Tar and Nicotine Deliveries

As noted earlier, competition- and demand-driven factors played a role in the increases in

the tar and nicotine deliveries of light cigarette brands seen as the category developed. Market

research studies conducted by the firms suggest that smokers interested in healthier cigarettes

often regarded cigarettes lower in tar/nicotine as unsatisfying in taste (e.g., Udow, 1973).

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

"!More details on the construction of this measure are provided in our empirical section.!

!

"#!

Tobacco producers also found light cigarette smokers to be particularly prone to switching

brands as they searched for a better tasting health-conscious brand (e.g., Grabowsky, 1972; Dunn

and Johnston, 1966). Clearly, many smokers preferred the flavor and “kick” of full flavor

cigarettes, while they were attracted to the health benefits of lights. This tension posed a

dilemma for tobacco firms trying to positively differentiate their brands by satisfying consumers’

taste desires while simultaneously assuaging their fears of the health risks of smoking.

Producers thus had clear incentive to increase the tar and nicotine deliveries of cigarette

brands marketed as light. However, since cigarette smokers specifically chose light brands for

the health benefits associated with low tar and nicotine, salient increases in deliveries may have

raised alarm among consumers. They may also have elicited scrutiny from the FTC, who had

intervened in the late 1950’s when it perceived tobacco firms as advancing unsubstantiated

advertising claims regarding the tar/nicotine deliveries and filter efficiency of filtered brands

(McAuliffe, 1988).

Company memos indicate that producers were attuned to this issue of scrutiny. As noted

in a 1973 Philip Morris correspondence (Gray, 1973):

Government, scientists, and cigarette manufacturers are all interested in the tar and

nicotine deliveries of various brands of cigarettes. The answer to the question marketing

people are most interested in determining is the extent to which the smoker is aware and

reacts to these figures. In the U.S.A. tar and nicotine numbers are printed in every

cigarette ad, and the total list of brands is systematically reported by the Federal Trade

Commission.

During the 1970s and 1980s, producers assessed how carefully consumers scrutinized

brands’ actual tar and nicotine deliveries through market research studies. For example, a 1975

report for Lorillard found the group of smokers actively comparing numbers to be “large and

growing” and consequently advocated reducing tar and nicotine deliveries for the brand Kent

!

"$!

(Foote, Cone, and Belding Advertising, Inc. 1975). By the early 1980s, however, a number of

different studies found that the great majority of consumers did not pay attention to specific tar

and nicotine numbers but were aware of the general tar category to which brands belonged (for

examples, see Medicus, 1982 and Daniel, Rowe, and Tindall, 1981a). Choice of brand names

(such as including terms like “light” or “mild” in a name) played a significant role in perceptions

of category membership. For example, a 1983 Brown and Williamson study found:

…it appears that consumers have a general impression of how category identifiers (i.e.:

“lights”, “ultra”, “milds”) relate to tar levels. When given a “family of brands” (i.e.:

KOOL), most consumers can correctly arrange them from highest tar (KOOL full-taste)

to lowest tar (KOOL Ultra). (Woods, 1983)

A 1980 Philip Morris document (Tindall, 1980) reached a similar assessment: “Smokers’

perceptions of the tar deliveries of low-tar brands appear to be more strongly influenced by the

brands’ general classification than by FTC tar” measurements. This suggests producers’ choice

of label influenced smokers’ perceptions of how healthy a cigarette was regardless of its

underlying properties.

Formal theory on category perceptions suggests that a decrease in direct scrutiny of

membership features is a natural by-product of increasing category taken-for-grantedness, and

thus generalizable beyond the cigarette case (DiMaggio, 1997; Hannan et al., 2007; Hsu et al,

2011). In the early stages of a category’s development, market participants must attempt to

determine which membership claims they regard as valid even as they are still making sense of

and updating their category-level beliefs. As a result, the process of evaluating potential

category members is likely to require considerable time and effort, with careful attention to the

various features of category claimants (Hannan et al, 2007).

!

"%!

As market participants develop a clearer sense of which characteristics are relevant for

category membership, the speed and sense of confidence with which participants evaluate

membership claims increases (Lurigio and Carroll, 1985; Clark and Wilkes-Biggs, 1986;

Vygotsky, 1987). As opposed to earlier developmental stages, when participants scrutinize

claimants carefully for all of the characteristics that indicate category belonging before granting

membership, participants for categories with greater taken-for-grantedness assume more

category-consistent characteristics by default (Hannan et al., 2007).

In the extreme, participants automatically fill in an entire category schema (that is,

assume by default that a claimant has all the characteristics representative of a category member)

based on the mere application of a category’s label. For such highly taken-for-granted categories

(Jepperson, 1991; Suchman, 1995), recognition of members becomes rapid and automatic, as

participant’s well-formed category schemas “provide default assumptions about their

characteristics, relationships, and entailments under conditions of incomplete information”

(DiMaggio, 1997: 269). When objects are commonly linked to a highly taken-for-granted

category, differences between them are largely ignored or dismissed as inconsequential

(Zerubavel, 1991; Weick, 1995; DiMaggio, 1997).

Such perceived homogeneity within the light category was observed in a 1976 study

conducted for Philip Morris (Brand, Gruber, and Co., 1976):

There appear to be only two classes of cigarettes in the minds of most consumers –

regular and low tar. Whatever variations there are truly in the market are perceptually

subsumed within these classes…Any cigarette that makes any kind of low tar claim

belongs in the low tar class...For most people looking for a low tar cigarette, almost any

low tar cigarette will suffice.”

This quote indicates that perceptions and evaluations of light cigarettes were becoming

categorical (rather than continuous along the dimensions of tar and nicotine) around this time.

!

"&!

This general shift towards categorical evaluations allowed producers to focus less in their

claiming efforts on the characteristics that make them or their offerings part of a category (since

these are assumed to be homogeneous among category members) (Lounsbury and Glynn, 2001;

Navis and Glynn, 2010). In keeping with this, our coding of light cigarette ads shows that

producers decreasingly coupled public claims regarding a brand’s light category membership

with specific tar and nicotine deliveries as the category developed.

Figure 5 reports the proportion of light cigarette ads listing tar and nicotine deliveries

numbers in their main body. This figure shows a steady decline in proportion of ads listing tar

information from 1.0 in 1964 to around 0.63 in the mid-1970’s. Starting in the late 1970’s, there

was another sharp decline. By 1990, approximately 1 in 18 ads listed tar numbers in their main

body.

This figure shows a slightly different pattern for nicotine discourse in light cigarette ads.

While there was also a major decline in nicotine discourse over the period studied, an interesting

divergence in patterns between tar and nicotine ad discourse can be seen during the latter part of

the 1970’s. The decline in reporting of nicotine deliveries was sharp starting in the mid-1970s

while it leveled off for tar deliveries over this time period; as a result, while over half of ads

sampled reported tar deliveries in 1980, only about 1 in 13 reported nicotine deliveries that same

year.

The main focus of our empirical investigation is whether increasing taken-forgrantedness of light cigarettes as a safer cigarette type (and the associated decrease in scrutiny of

tar and nicotine deliveries) was a major factor driving producers’ adjustments in tar/nicotine

deliveries. Internal documents provide some indication of this. A 1981 report for Philip Morris

(Daniel, Rowe, and Tindall, 1981b) concluded that:

!

"'!

If, in attempting to switch to lower-tar brands, smokers are in fact guided by their

perceptions of tar rather than by actual tar numbers, the best strategy for a company

should, be to have the highest tar brands in each perceived tar delivery segment.

And a 1979 Brown and Williamson product development proposal for a new cigarette

codenamed “Brand B” argues that (Tighe, 1979: 2):

An entry into the low ‘tar’ sub-segment can be gained by positioning the brand strongly

as a low ‘tar’. No specific numbers need to be highlighted to support this claim, just firm

mention of low ‘tar’. This, therefore, allows for the optimum development of the product

as long as it is under 10 mgs., i.e., a single digit ‘tar’ level (this is a judgment).

As the above quote highlights, Brown and Williamson sought to strongly invoke the low

tar category label for this proposed brand while simultaneously increasing its tar delivery in an

effort to increase consumer taste satisfaction. More generally, this proposal suggests efforts by

producers to understand and experiment with how high they could set tar and nicotine deliveries

for products marketed as light without attracting negative reactions.

The idea that taken-for-grantedness provides producers with the opportunity to

strategically manipulate core category features is consistent with the formal theory proposed by

Hannan et al. (2007). If market participants fill in more and more of a category schema by

default, this means they reduce the number of actual features that they match against the category

schema before granting membership. As a result, participants will tend to perceive claimants to

be better fits with a category schema than they would have in earlier stages when they

scrutinized claimants more thoroughly (Hsu, Hannan, and Pólos, 2011). One implication (which

is both theoretically and empirically unexplored) of this lower scrutiny is greater ability for

producers to manipulate category-related features without being detected.

Together, the empirical evidence and formal arguments lead us to expect that the

decrease in consumers’ scrutiny of membership criteria associated with increasing category

!

"(!

taken-for-grantedness opened up the opportunity for tobacco firms to inconspicuously increase

tar and nicotine deliveries for light cigarettes. This encouraged firms to focus on positively

differentiating their products through enhanced taste delivery, while avoiding negative consumer

and public official reactions to the increase in unhealthy components that enabled this.

Hypothesis 1: As the taken-for-grantedness of the light cigarette category increases,

producers increase tar and nicotine deliveries of brands marketed as light.

We next refine our theory by considering variation in producers’ incentives to weaken fit

with particular membership features. Company memos suggest a key difference in tobacco

firms’ incentives for tar versus nicotine. At a 1967 research conference, scientists working for

the tobacco producers asserted that “smoking is an addictive habit attributable to nicotine”

(Glantz et al., 1996: 80). The following 1963 Brown and Williamson memo (Griffith, 1963) also

attests to early recognition of nicotine’s importance as well as the ability of tobacco

manufacturers to manipulate nicotine deliveries:

Nicotine is by far the most characteristic single constituent in tobacco, and the known

physiological effects are positively correlated with smoker response…I think that we can

say even now that we can regulate, fairly precisely, the nicotine…levels to almost any

desired level management might require. Of this I am confident.”

Thus, although significant removal of nicotine from cigarettes was technologically

possible, tobacco producers worried that it would eliminate cigarettes’ addictive properties and

erode demand (Glantz et al., 1996). Firms dedicated considerable effort to determining the

minimal dosage of nicotine necessary for maintaining cigarette’s addictive properties (Hurt and

Robertson, 1998). As S. J. Green (1980: 2), a research director at British American Tobacco

held:

!

")!

Nicotine is an important aspect of “satisfaction,” and if the nicotine delivery is reduced

below a threshold “satisfaction” level, then surely smokers will question more readily

why they are indulging in an expensive habit.

Green goes on to state the following:

It is advocated that every opportunity is taken to separate tar and nicotine in the minds of

consumers and legislators, and that we should be aware of the long-term dangers of

following the crowd into ultra-low nicotine deliveries.

This sentiment is echoed in a 1980 Philip Morris memo regarding the production of cigarettes

with high nicotine to tar ratios (Dunn, 1980: 1):

If even only some smokers smoke for the nicotine effect (I personally believe most

regular smokers do), then in today’s climate we would do well to have a low [tar

delivering cigarette] that can supply adequate nicotine.

Producers believed that continued success of light cigarettes would depend on diverting

scrutiny away from nicotine and towards the other core membership feature of tar. This was

reflected in Figure 5, which showed mentions of specific tar deliveries in light cigarette ads to be

more prevalent relative to nicotine delivery mentions after 1970. Differences between mentions

of tar versus nicotine are even more apparent in Figure 6, which reports the yearly proportions of

light cigarette ads with any reference to the terms “tar” or “nicotine” in their main body. In the

early period, the proportion of light cigarette ads mentioning the term nicotine is actually greater

than those mentioning tar during the earliest period of the category’s development. However,

mentions of tar increase from 1964 to the early 1970s, while they decrease gradually for nicotine

until 1975, when there is a sharp drop-off in mentions. In 1980, all light cigarette ads included a

mention of tar while approximately 0.15 ads mentioned nicotine. Mentions of tar begin to drop

off sharply after 1980, but remain substantially higher than nicotine mentions throughout the rest

of the study period.

!

"*!

Internally, confidential memos capture efforts by producers to decouple tar from nicotine

deliveries in the production of light cigarettes. Since conventional techniques for reducing tar

(like adding a filter) reduced tar and nicotine proportionally, producers sought to develop

sophisticated techniques to maintain tar levels while increasing nicotine (Brandt 2007). A

number of company memos document interest in the development of light cigarettes with higher

nicotine-to-tar ratios, which could be marketed as health oriented yet still guarantee addiction

among smokers (e.g., Dunn, 1980; Spears and Jones, 1981; Fisher, 1983).

Overall, this suggests that producers had greater incentive to manipulate brands’ nicotine

relative to tar deliveries and worked to decrease scrutiny of nicotine deliveries. Accordingly, as

the light cigarette category became more taken-for-granted and opened up opportunity for

producers to weaken fit with membership features, we expect the following:

Hypothesis 2: As the taken-for-grantedness of the light cigarette category increases,

producers increase nicotine deliveries disproportionately more than tar deliveries for

cigarette brands marketed as light.

In a final hypothesis, we consider the implications of light cigarette brand increases in tar

and nicotine for the boundaries demarcating different types of cigarettes. Research on category

blending processes in market contexts suggests that perceived similarity of features (Hannan,

2010; Negro, Hannan, and Rao, 2010) or salient acts of borrowing between categories (Haveman

and Rao, 2006; Rao, Monin, and Durand, 2005) weaken category boundaries. In the cigarette

case, since tar and nicotine deliveries were the central distinctions between light and full flavor

cigarettes, increases in tar and nicotine deliveries among light brands had the potential to weaken

the boundary between these two categories.

!

#+!

Further contributing to this potential was the trend in tar/nicotine deliveries among full

flavor cigarettes. Just as health concerns with smoking propelled growth of the light cigarette

category, they also exerted downward pressure on full flavor cigarettes deliveries. In a Philip

Morris internal correspondence, Daniel et al. (1981b) cite the potential threat from regulatory

bodies to tax cigarettes in proportion to tar levels and potential negative publicity generated by

FTC tar/nicotine listings as potential reasons for the systematic decline in full flavor brands.

This decline made any salient increase in light cigarette tar/nicotine more apt to blur the

distinctions between the two categories. Given the positive health-related attributions associated

with light cigarettes and the increasing importance of light cigarette sales to the industry as light

category market shares increased, such a blurring was not likely to be in firms’ interests.

Studies of boundary work reveal a diversity of practices used by social actors to create

and institutionalize conceptual distinctions between categories (Gieryn, 1999; Lamont and

Molnár, 2002). In the cigarette case, producers created and promoted the symbolic boundary

between light and full flavor brands through advertisement discourse as well as through

advertising imagery (for example, emphasizing high tech imagery to highlight the scientific

progress associated with light cigarettes) (Pollay and Dewhirst, 2002). Differences between light

and full brands were also accentuated through package design choices (Wakefield et al., 2002).

For example, as noted in 1986 British-American Tobacco Co. report (Miller, 1986):

Lower delivery products tend to be featured in blue packs. Indeed, as one moves down

the delivery sector then the closer to white a pack tends to become. This is because white

is generally held to convey a clean, healthy association.

Internal memos also suggest firms worked to distinguish light cigarettes from full flavor

brands by soliciting credible endorsements from politicians and scientists for light cigarettes as a

safer type of cigarette (e.g. Wells, 1982).

!

#"!

Zerubavel (1997) proposes that taken-for-grantedness not only promotes perceptions of

homogeneity among category members, but also increases perceived social distances between

members of different categories. Categorization thus transforms gradual distinctions into

discrete divisions. For example, hotels designated to be three versus four-star come to be viewed

as “qualitatively different”, even though membership within these categories can more accurately

be characterized as a “matter of degree” (Zerubavel, 1997: 66). Similarly, smokers came to

perceive cigarettes as either “full flavor” or “light”, perceiving these as qualitatively different

classes of cigarettes (Brand, Gruber, and Co., 1976).

This suggests that, in periods of lower taken-for-grantedness, maintaining a distinction

between full flavor and light cigarette categories required significant differences in tar and

nicotine deliveries. This placed an upper bound on the possible delivery levels for light

cigarettes. However, as the taken-for-grantedness of light cigarettes increased, the perceptual

(but not the actual) gap between full flavor and light categories widened. This clear distinction

between the two categories opened up opportunities for firms to increase light cigarette tar and

nicotine deliveries into their full flavor tar/nicotine spectrums without concern for a blurring of

category boundaries.

Hypothesis 3: As the taken-for-grantedness of the light cigarette category increases, the

tar/nicotine of producers' light brands will increasingly blend into the tar/nicotine

delivery spectrum of their full flavor brands.

Quantitative Analyses

To test our hypotheses, we collected trademark and basic type (filtered or non-filtered,

menthol, etc.) information on all cigarette brands manufactured and marketed in the U.S. from

1963-1993 from the Tobacco Merchants Association’s (TMA) Directory of Cigarette Brands

(4th edition). This directory also provides a complete listing of the FTC’s tar and nicotine

!

##!

measurements, regularly conducted on all nationally available cigarettes as well as all cigarettes

marketed as light since 1967 (FTC news release, 1967). The major manufacturers also provided

the FTC with tar and nicotine measurements for generic, private labels, and other brands not

widely available through a compulsory process.

To complement this data, we collected monthly internal Intelligence Reports conducted

by Philip Morris on the tar and nicotine deliveries of its competitors’ brands from 1960 to 1993

(http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/). Both Philip Morris and the FTC use a standardized smoking

machine test known as the Cambridge Filter Method. In total there are 757 brands with

tar/nicotine information in our dataset, produced across 7 different cigarette firms.

Measures:

Dependent Variables: To test the hypothesis that increases in tar and nicotine deliveries as light

category taken-for-grantedness increases (H1), our first two dependent variables are the yearly

tar and nicotine deliveries of light cigarette brands. To test whether there was a disproportionate

increase in nicotine relative to tar (H2), we calculated the nicotine-to-tar ratio for cigarette

brands from this data. For interpretability, nicotine deliveries are multiplied by 10 and nicotineto-tar ratios by 100 in our models. To test whether light brands increasingly blended into the full

flavor spectrum as light category taken-for-grantedness increases (H3), we calculated the yearly

count of a manufacturer’s light brands whose tar and nicotine deliveries exceed the lower

boundary of that manufacturer’s full flavor tar/nicotine delivery spectrum.

Independent variable. Our main independent variable is the taken-for-grantedness of the light

cigarette category. As noted earlier, we follow Colyvas and Powell (2006) in treating a decrease

in explanatory discourse regarding a category as a visible marker of its taken-for-grantedness.

To generate this measure, we collected media articles that referenced the light cigarette category

!

#$!

and/or its members from each year of our study period and coded them for the extent to which

they included detailed explanation of the category’s features and membership criteria. Our

sample consisted of three articles per year from each of four sources: The New York Times, Los

Angeles Times, Washington Post, and Wall Street Journal (360 articles total).

To construct our coding scheme, we started with a subsample of media articles from

across the different years of our study to determine the features of the light cigarette category

explicated through media accounts. We built the coding scheme iteratively in this fashion. We

first coded a small set of articles separately, compared and contrasted our codes, and used these

comparisons to make refinements to the coding scheme. After we converged on a stable set of

codes, we applied it to the entire sample of media reports. Our final coding scheme consisted of

the following dimensions: 1. explication of the components that constitute a light cigarette like

tar, nicotine, or related gas/smoke components relevant to cigarette smoking and/or its

physiological consequences, 2. explication of amount of tar/nicotine deliveries, 3. description

and/or depiction of the brand’s filtration method, and 4. description of other methods (besides

filtration) which constitute a light cigarette, such as tobacco blend or paper porosity. 5. how the

light category and its members were referenced in the article (such as “cigarettes with reduced

tar and nicotine deliveries” versus “light cigarettes”), 6. references to scientific research or

testing involving light cigarettes, and 7. explication of the health gains associated with light

cigarettes.

We then applied this coding scheme to each of the articles in our sample, with each coauthor coding roughly half of the total sample of articles. To assess inter-rater reliability, we

tasked a third individual without any exposure to the purpose of the study to apply the coding

!

#%!

scheme to the entire set of articles. The inter-rater agreement on each of the dimensions was

high (93.1% codes matched; kappa = 0.71).

To create our main light category taken-for-grantedness we summed values across the

seven dimensions2. We also created a nicotine-specific taken-for-grantedness measure reflecting

the extent to which media report explanations of the light category included references to

nicotine (as opposed to both tar and nicotine) for supplementary analyses presented in Models

1.4 and 3.4.

Other control variables.

We included lagged controls for total firm sales and media visibility (t-1) since larger and

more visible producers may have attracted greater scrutiny from regulators and anti-tobacco

groups, causing them to be more conservative in tar and nicotine deliveries. Sales data came

from John C. Maxwell, Jr.’s industry surveys, which reported yearly sales for brands produced

by the major tobacco firms (http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/).3 Firm media visibility was

calculated as the yearly counts of articles referencing each firm in our sample in The New York

Times, Wall Street Journal, and Washington Post.

We also control for firm’s R&D investments in the tobacco industry, since increases in

tar and nicotine deliveries may have been driven by enhancements in firms’ ability to manipulate

the physical design of cigarettes. We gathered patent data for all producers in our database from

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

#!In supplementary analyses (available upon request), we examined several alternative measures of

category taken-for-grantedness, including i. the light category’s share of total U.S. cigarette market sales,

ii. density of brands within the light cigarette category, and iii. degree to which producers explicated the

light category to consumers in light cigarette print advertisements. These measures are highly correlated

with our main independent variable and produce consistent findings in our main models.

!

$!While

we do not have sales data for non-major firms, the tobacco industry’s status as a six-firm

oligopoly makes this bias somewhat less problematic (Barnett, Keller, and Hu, 1995). Among the

majors’ brands, we are not able to determine sales for brand families with non-significant market share,

which Maxwell grouped under the category of ‘Others’. Brand families for which we lack sales data were

assigned the lowest sales observed by the Maxwell surveys in their respective year.!

!

#&!

the NBER U.S. Patent Citation Database (see Hall, Jaffe, and Trajtenberg, 2001) and computed

each firm’s yearly stock of patents using the number of patents applied for, weighted by the

number of received patent citations (the lagged natural log of this measure is used in our models)

(see Hall, 1990; Hall and Mairesse, 1995).

We include several macroeconomic controls that might affect producers’ choices

regarding tar and nicotine deliveries. First, we control for changes in U.S. smokers’

demographics through measures of the estimated consumption per person for females and

individuals under 40 years of age, updated at five-year intervals throughout our study period

(source: IMASS Database, 2009). Various company market research reports found that female

smokers exhibited a greater preference for lower tar offerings than males and constituted a core

demographic of this new category (e.g., Oglesby, 1976). There was also some evidence that

younger smokers were an important demographic to the light category and had different taste

preferences relative to older smokers (e.g. Marcial, 1977). Changes in both demographics might

have thus prompted changes in cigarettes’ tar/nicotine deliveries.

We also control for the lagged count of new U.S. state legislation passed regarding

tobacco excise taxes (source: National Cancer Institute, http://www.cancer.gov). Such

legislation may have presented an incentive for producers to increase tar and nicotine deliveries

in order to retain existing smokers in the face of increasing economic threat.

At the brand level, we control for whether a brand was marketed as “ultra light,” since

targeting this subsegment within the light category likely resulted in lower tar and nicotine

deliveries.4 In models including established brands, we include a control for brand age (number

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

4

Supplementary analyses excluding the control for whether a brand was marketed as “ultra light” produce

results consistent with our main findings.

!

#'!

of years since a brand’s first trademark use) to allow the possibility that the likelihood of

increases in tar/nicotine change as a brand matures.

Competition-related control variables. We introduce a number of market-, firm-, and brand

family-level controls to examine the extent to which our story is attributable to taken-forgrantedness versus factors related to competitive positioning.

We first address the possibility that tar/nicotine deliveries may have increased simply

because consumers demonstrate a preference for higher tar/nicotine offerings by controlling for

the average tar and nicotine of the five light brands with the largest market share (one- and threeyear moving average, lagged by one year). The higher the most popular light brands are in tar

and nicotine deliveries, the higher the rest of the market is likely to move.

We also control for the role rivalry may have played in influencing producers’ tar and

nicotine positioning by controlling for the average tar and nicotine of all light brands produced

by rival firms, lagged by one year. Increases in rivals’ tar and nicotine deliveries may have

encouraged a firm to increase the deliveries of its own brands. We control for the possibility that

rivals’ positioning in the full flavor category may have affected the focal firms’ light positioning

by including average tar/nicotine of rivals’ full flavor brands in our models. In supplementary

models (available upon request) we introduce into our models controls for variation in the tar and

nicotine deliveries of rivals’ brands (standard deviation of rivals’ brands, lagged by one year),

since greater variation may encourage the focal firm to experiment with increases in tar and

nicotine deliveries. Results for our main variables are consistent with those presented here.

To further assess the possibility that firms increased tar and nicotine deliveries in

response to competitive pressures, we include a Herfindahl!index reflecting the amount of

!

#(!

competition among firms in the light cigarette category. This is calculated as the sum of squares

of firms’ market share within the light cigarette category.

At the firm-level, we introduce a number of controls to account for the impact of firms’

attempts to differentiate light brands from other offerings in their overall portfolio. These

include the yearly average tar and nicotine deliveries of full flavor brands (higher

deliveries among a producer’s full flavor brand deliveries may have encouraged higher tar and

nicotine deliveries among its light brand offerings), the count of brands marketed as light

(increases in tar/nicotine deliveries may have resulted from firms’ attempting to differentiate

their light offerings from other light offerings), and the count of brands marketed as ultra light

(increases may have been the result of producers trying to differentiate light brands from

offerings in the ultra light sub-category). To control for differentiation pressures at the brand

family level, we include a measure reflecting the yearly counts of brands marketed as light and

ultra light in our models5.

Estimation. We examine the impact of light cigarette category taken-for-grantedness on

producers’ adjustments to the tar and nicotine deliveries of brands marketed as light in several

ways. First, we examine the initial tar/nicotine positioning of new brands marketed as light. We

isolate our analyses first to new brands since market offerings are presumably under higher

scrutiny when they are first released onto the market. We next examine changes in the

tar/nicotine deliveries of established brands to assess whether changing levels of category takenfor-grantedness affected producers’ likelihood of adjusting the features of existing offerings.

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

5

We do not include a control for full flavor tar and nicotine at the brand family level because a number of

brand families do not have any full flavor offerings.

!

#)!

Finally, we examine changes in the tar/nicotine differences between producers’ light and full

flavor brands.

Changes in new brands’ tar and nicotine deliveries are estimated using multilevel models

which account for nesting within firms and within brand families (Bryk and Raudenbush, 1992;

Snijders and Bosker, 1999). This allows us to investigate firm- and brand family-level factors

that may affect choices in the initial positioning of new cigarette brands. This analysis does not

include brands whose earliest FTC tar and nicotine measurement occurred more than three years

after its first trademark use since such brands can no longer be regarded as ‘new’.

We analyze changes in established light brands’ tar/nicotine deliveries through two

approaches. First, we examine whether category taken-for-grantedness influenced the speed by

which producers moved to increase established brands’ tar and nicotine deliveries. In these

models, we used r(t), the instantaneous rate of increasing tar/nicotine deliveries beyond the initial

deliveries reported for each brand, defined as

! ! ! ! !"#!"!!

!"!!!!!!!!!"!!!!!

!"

.

After experimenting with several classes of parametric and semiparametric models, we found the

hazard rate exhibited a monotone function that is well fitted by a Weibull specification. In these

models, unobserved heterogeneity at the firm level is accounted for through a gamma shared

frailty specification (Gutierrez, 2002). In a second set of models involving established brands,

we analyzed the degree to which producers adjusted brands’ tar/nicotine deliveries through

multilevel models which account for clustering at three levels: within firm, within brand family,

and within brand. Both sets of models are presented and discussed in the results section below.

We examine changes in how firms position their light versus full flavor offerings through

fixed effects negative binomial models estimating yearly variations in the counts of each

!

#*!

manufacturer’s light brands that exceed its minimum full flavor brand in tar and nicotine

deliveries.

Results

In Table 1, we estimate changes in the initial tar and nicotine deliveries of new cigarette brands

marketed as light as light category taken-for-grantedness increases. Model 1.1 estimates initial

nicotine and Model 1.2 estimates initial tar deliveries.

A number of control variables have significant effects on initial tar and nicotine

deliveries. Among the noteworthy effects, we find that initial tar and nicotine deliveries increase

with greater under-40 cigarette consumption and with greater average tar/nicotine of a firm’s full

flavor brands, while they decrease with greater female cigarette consumption and with the

marketed of a new cigarette brand as “ultra light”. Tar/nicotine deliveries also decrease with

greater count of light brands at the firm level, greater ultra light brands at the brand family level,

and greater average tar among the top five light brands in terms of market share decreases

expected tar for new light brands. Finally, greater light category competition (sum of squares of

firms’ market share in the category) increased tar deliveries.

Net of these controls, we find significant positive main effects of light category taken-forgrantedness on both initial tar and nicotine deliveries for new brands (Hypothesis 1). To

examine Hypothesis 2, we standardized the coefficients from Models 1.1 and 1.2 and compared

the relative magnitudes. In our estimates of tar deliveries, the standardized coefficient for light

category legitimation is 0.737; for our estimates of nicotine deliveries, it is 1.071. This suggests

that new brands’ nicotine deliveries increase more with increases in light category taken-forgrantedness relative to their tar deliveries.

!

$+!

To further investigate Hypothesis 2, we estimate models with the initial nicotine-to-tar

ratio as the dependent variable. The results in Model 1.3 find the effect of light category takenfor-grantedness on this ratio to be positive but not statistically significant (p>0.10). As a last

examination of the relationship between category taken-for-grantedness and nicotine versus tar

deliveries, we estimate the effect of a measure of light cigarette taken-for-grantedness that

focuses on discourse related to nicotine in Model 1.4. This allows us to better isolate the impact

that decreased scrutiny of nicotine-related features of the light cigarette category may have had

on firms’ nicotine delivery positioning. When this alternative measure of light category takenfor-grantedness is included in the model, we see a significant effect on initial nicotine-to-tar

ratios.

In the next set of models, we estimate producers’ rate to increasing tar/nicotine deliveries

beyond an established light brand’s initial levels. Models 2.1 (nicotine) and 2.2 (tar) show that

increasing light cigarette category taken-for-grantedness had a positive effect on the rate for

nicotine but not for tar. This difference is consistent with the idea that nicotine deliveries were

influenced more by changing light category taken-for-grantedness relative to tar. The rate of

increases to both tar and nicotine deliveries decreased with brand age but increased with higher

full flavor average tar/nicotine of a firm’s brands.

We also estimate the extent of changes in brands’ nicotine and tar deliveries through

multilevel models that include all brands, new and established. Models 3.1 and 3.2 suggest that

increasing light category taken-for-grantedness increased tar and nicotine deliveries among all

brands. In our standardized estimates for tar deliveries, the coefficient for light category takenfor-grantedness is 0.064 while the coefficient for nicotine is 0.177. This suggests, in support of

Hypothesis 2, that nicotine deliveries increase more with increases in light category taken-for-

!

$"!

grantedness relative to tar deliveries. Model 3.3, which estimates the nicotine-to-tar ratio as the

dependent variable, shows the effect of light category taken-for-grantedness on this ratio is

positive and significant.

The effects of control variables in Models 3.1 and 3.2 are generally consistent with their

effects on initial tar and nicotine deliveries, described earlier. There are a few noteworthy

differences. In multilevel models with all (not just new) brands, we see significant effects of

intensity of light category competition on both tar and nicotine deliveries, with greater

competition pushing tar and nicotine deliveries higher. We also find that, while firm-level ultra

light and brand-level light brand counts decrease tar and nicotine deliveries, greater brand family

ultra light brand counts increase tar deliveries.

Our last set of models estimate the yearly count of a firm’s light brands that exceed its

minimum full flavor brand tar/nicotine deliveries.6 In Model 4.1, we see increasing light

cigarette category taken-for-grantedness has a positive effect on the counts for nicotine but not

for tar. Among the control variables, we see that increased firm sales decrease the counts of light

brands exceeding the minimum full flavor tar/nicotine deliveries, while greater count of light

brands for the firm increases this count for nicotine.

Overall, our models present support for all three of our hypotheses. Net of a variety of

controls designed to address demand- and competition-based alternative explanations we find a

positive, significant effect of light category taken-for-grantedness on i. the initial positioning of

new light brands in terms of tar and nicotine, ii. the speed and extent of adjustments to

established light brands, and iii. the proclivity of producers to increase deliveries of their light

brands into their full flavor nicotine spectrum. Further, the effect of light category taken-for!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

6

The count of firms in this sample drops from 7 to 6 due to insufficient number of observations for one

firm (U.S. tobacco).

!

$#!

grantedness on nicotine deliveries was stronger and more robust across the different models, in

line with our expectation that nicotine deliveries increased disproportionately more with light

category taken-for-grantedness relative to tar.

Discussion

Our paper presents an alternative perspective to sociological studies of markets and

institutional approaches that equate taken-for-grantedness with increasing constraint on the

features of category members (DiMaggio and Powell, 1983; Lamont and Molnar, 2002; Ruef and

Patterson, 2009; Negro, Hannan, and Rao, 2010; Kovács and Hannan, 2010). We advance the

idea that the salience of product features to market participants plays a key role in whether

increasing taken-for-grantedness leads to increased constraint or flexibility in producers’ actions.

Departures from expected features only meaningfully affect category evaluations when they are

scrutinized by and salient to relevant participants. Existing studies largely focus on salient

departures such as the explicit adoption of features from multiple categories or producers’ claims

to membership in multiple categories. Our unique mix of historical insider documents and

product characteristic information allows us to study the alternative case in which departures go

under the radar.

Our study links current theorization on market categorization with the literature on

categorization more generally that highlights how schemas distort perception of category

members (Durkheim, 1912; Douglas, 1986; DiMaggio, 1997; Zerubavel, 1997). We thereby

extend the few existing studies within organizational sociology which recognize the gap between

expected and actual features of producers as a strategically important issue (Waguespack and

Sorenson, 2010; Granqvist, Grodal, and Woolley, 2013; Phillips and Kim, 2009). In their study

!

$$!

of the U.S. brewing industry, for example, Carroll and Swaminathan (2000) observe that contract

brewers often concealed the origin of their products (many of which were produced by mass

production breweries at lower cost) and deceptively marketed them as small production

microbrews in order to appeal to the lucrative microbrew market. We contribute to this issue by

highlighting how the opportunity for producers to depart from market participants’ expectations

without eliciting negative scrutiny systematically shifts as a category develops.

More broadly, our study points to the need to better unify ideas regarding categorical

constraint and producers’ strategic manipulation of category expectations. Studies investigating

how categorization schemes shape producer outcomes tend to portray market producers as

passive bystanders in categorization processes (e.g. Zuckerman, 1999; Hsu, et al., 2009; Ruef

and Patternson, 2009). Other studies, on the other hand, focus on how producers actively work

to advance their strategic interests through categorization. Strategic concerns have been found to

shape which categories firms choose to claim membership within (Porac, Wade, and Pollock,

1999; Phillips and Kim, 2009). Studies also suggest the way categorization schemes are created

and used by market intermediaries is influenced by powerful producers (Lounsbury and Rao,

2004; Waguespack and Sorenson, 2010) as well as by the nature of the exchange relationships

between intermediaries and producers (Fleischer, 2009).

Increasingly, researchers have noted that producers’ category-related claims differ

according to the development of their relevant market categories. Multiple studies suggest the

taken-for-grantedness of a category shapes how producers define their category and categorical

identities to other market participants (Lounsbury and Glynn, 2001; Kennedy, 2008; Navis and

Glynn, 2010; King, Clemens, and Fry, 2011; Granqvist, Grodal, and Woolley, 2013). A recent

study by Pontikes (2013) further suggests that the extent to which a category is clearly

!

$%!

demarcated from others in its domain shapes a producer’s decision to claim membership within it

versus advance a new market category. Such studies shed light on the way producer’s categoryrelated claims change with the different strategic needs presented by different types of shared

categorical understandings. Our study extends this literature by demonstrating that not only

strategic claims, but also the relationship between what producers claim and what features they

actually adopt, systematically co-evolve with the cognitive constraints imposed on them by

category systems.

Our findings also draw conceptual links between the study of categories and new

institutional research on decoupling, subfields within organizational sociology that have

remained largely disconnected. Accounts of decoupling generally incorporate notions of

strategic agency by considering variation in actors’ responses to institutional pressures (e.g.,

Oliver, 1991; Greenwood and Hinings, 1996; Davis and Greve, 1997; Lounsbury, 2001; Bromley

and Powell, 2012). While traditional accounts usefully connect variation in responses to

individual-level interests and power dynamics, less is known about the broader conditions

driving the proclivity to engage in decoupling, with two notable exceptions.

First, studies of temporal variation in the adoption of practices suggest that early adoption

tends to be driven by technical or efficiency motives, while later adoption is largely driven by

concerns with legitimacy (Tolbert and Zucker, 1983; Westphal et al., 1997). This is consistent

both with the notion that pressures for conformity increase with taken-for-grantedness and that

taken-for-grantedness may drive the ceremonial adoption of category features. Our account

sharpens understanding of the cognitive microprocesses enabling these decoupling dynamics to

unfold and highlights the importance of attending to evolution in perceptions.

!

$&!

A second exception is accounts of institutional recoupling, which suggest that increased

attention and pressures from external stakeholders may drive an increase in the substantive

linkage between policies and practices (see Bromley and Powell, 2012 for a review). Studies

have linked recoupling to pressures from internal power dynamics (Tilcsik, 2010),

commensuration (Espeland, 1998) and social movements (Hallet, 2010). We believe these

various pressures could be commonly connected to changes in market participants’

understandings and scrutiny. A productive area for future research would be to integrate

processes of coupling with accounts of behaviors which decrease category taken-for-grantedness

such as salient acts of non-conformity by high-status actors (Rao et al., 2005) and the number of

perceived category violations (Hannan et al., 2007). Tying these various fragments into a

cohesive theory would likely provide a useful foundation for integrative insights.

It may also be useful to incorporate insights from related work within cultural sociology

on commensuration—the transformation of different qualities of objects into common,

simplifying metrics such as price, risk, and quality rankings (Espeland and Stevens, 1998).

Scholars studying commensuration observe that such metrics have been increasingly adopted

across a variety of social contexts in response to a growing demand for accessibility of

information and accountability (Espeland and Sauder, 2007). Like categories, commensuration

can be viewed as a tool for facilitating information processing, as multiple uncertain qualities are

reduced to simple, easily comparable metrics. Even more, categorization plays a central role in

commensuration; a common product of commensuration is the creation of categories of value

that, once adopted, become imbued with “meaning, consequence and objectivity” (Espeland and

Stevens, 1998: 325).

!

$'!

In the case of cigarettes, actors’ health-based goals drove the creation of a simplifying

hierarchy based on tar and nicotine numbers that formed the backdrop of the creation of

categories such as “full flavor” and “light”. These categorical distinctions became cognitive

shortcuts that consumers could easily digest. By integrating insights from cognitive work on

categories, we are able to explain why, as these simplifying categorical distinctions became

taken-for-granted, attention to the actual numbers they were based on disappeared. This