school yeArs

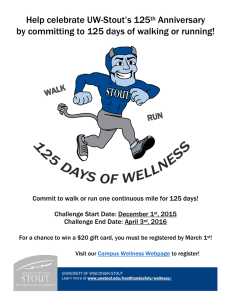

advertisement