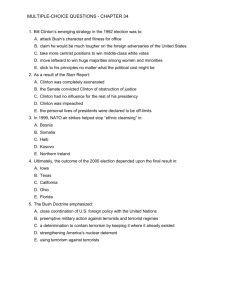

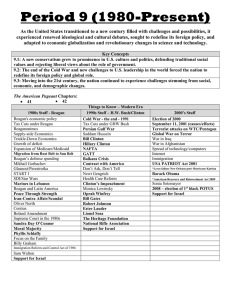

31 Beyond the Cold War: Charting a New Course, 1988–1995 T

advertisement