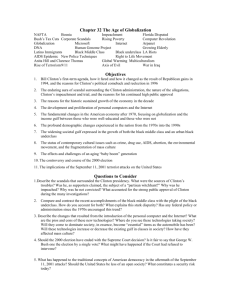

32 New Century, New Challenges, 1996 to the Present F

advertisement