Document 11650481

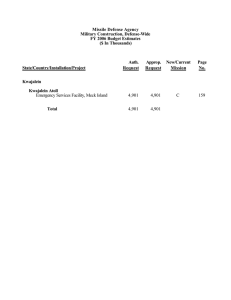

advertisement