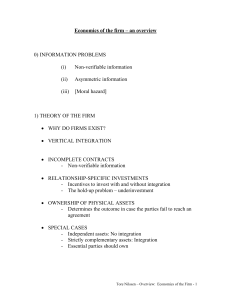

ECON 4245 – ECONOMICS OF THE FIRM Overview of the course

advertisement

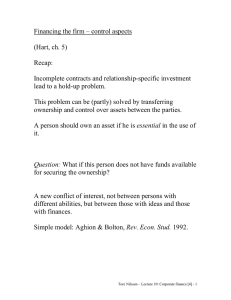

ECON 4245 – ECONOMICS OF THE FIRM Overview of the course Basic questions: • Why do firms exist? Why do firms • buy other firms? • merge? • go bankrupt? • How are firms financed? • How are firms managed? Basic analytical tools: • Microeconomics, in particular: • Economics of information Economics of the firm – Tore Nilssen – Lecture 1: Theory of the firm – page 1 The economics of information – the big picture Three information problems: • Hidden information – adverse selection Financing the firm • [Hidden actions – moral hazard] Managing the firm • Unverifiable information – incomplete contracts Theory of the firm Economics of the firm – Tore Nilssen – Lecture 1: Theory of the firm – page 2 Theory of the firm Reading: Oliver Hart, Firms, Contracts, and Financial Structure, chs. 1-4. [A broader picture: ECON 4920 – Economic Systems, Institutions and Globalization] Question: Why do firms exist? Refined question: Why are some transactions carried out within a firm and others in the market? • outsourcing • make or buy • takeovers Another interesting question: What do firms do? Do they maximize profits? - hidden action Economics of the firm – Tore Nilssen – Lecture 1: Theory of the firm – page 3 Why do firms exist? Traditional economic theory: Technological explanation. Firms are big because of economies of scale. Firm size determined, in the long run, by the shape of C(q)/q. C’(q) q* C(q)/q q • Why is the curve U-shaped? • Managerial problems in big firms? • Plant/Division vs Firm - One big firm, many divisions each of size q* Economics of the firm – Tore Nilssen – Lecture 1: Theory of the firm – page 4 Agency theory Incentives problems within the firm q = g(e, ε) q – observed output e – manager’s effort ε – random variable Owner cannot know whether high q is due to high effort or shear luck. Trade-off: Incentives vs. risk sharing P(q) – payment to manager as a function of the observed q P’(q) high: incentives high but manager takes on too much risk P’(q) low: risk sharing more appropriate but incentives low The same problem occurs both within the firm and between firms. The agency theory cannot easily be applied to our question, Why are some transactions carried out within a firm and others in the market? Economics of the firm – Tore Nilssen – Lecture 1: Theory of the firm – page 5 Transaction-costs theory Ronald Coase - Nobel laureate 1991. ”The Nature of the Firm” (1937). Inside or outside the firm? • Outsourcing; Make or buy Some market transactions are costly, and it may therefore be cheaper to make the item oneself rather than buy it. • Market transactions are governed by contracts But: • Contracts are incomplete - unforeseen contingencies - difficult to agree on terms - costly to write contracts … leading to: the property-rights approach • The contract is used to determine ownership – the right to decide over the assets involved. Economics of the firm – Tore Nilssen – Lecture 1: Theory of the firm – page 6 Examples of contract incompleteness • Unforeseen contingencies: A in Paris is supposed to deliver equipment to B in Oslo. But no-one has anticipated a strike among air-traffic controllers. • Other possible unforeseen contingencies: - an unanticipated change in demand for B’s products - a change in regulations of A’s and/or B’s businesses - innovations that may, for example, make A’s products obsolete as input in B’s production. • Simplicity: The contract specifies that A sends one item in each delivery, even though B’s requirements varies with wear and tear of her existing equipment, because it is too complicated to specify exactly under which conditions more than one item is needed, or those conditions are unknown. • Limitations: The contract is limited to one year, because it is difficult for B to see what her demands will be after that, and it is difficult for A to see what his abilities to deliver will be. Economics of the firm – Tore Nilssen – Lecture 1: Theory of the firm – page 7 The consequence of incomplete contracts Revisions and renegotiations. • Find a new delivery time given the strike and how the costs of the delay are to be distributed between A and B. • Order more items when the contracted delivery is too small and agree on the price of the extra items • Extend the duration of the contract and agree on terms for the next period Question: Can the law fill in gaps in contracts? Economics of the firm – Tore Nilssen – Lecture 1: Theory of the firm – page 8 Problems with renegotiations • Negotiations over revisions take time and resources • At the stage of renegotiation, the two parties may be asymmetrically informed • B has received information, since the initial contract was written, about the demand for its products. This information is not known to A. This makes it difficult to agree on a revised contract. These are ex-post costs of renegotiation. Economics of the firm – Tore Nilssen – Lecture 1: Theory of the firm – page 9 But why bother to renegotiate? • Renegotiation would not be necessary if the parties could costlessly switch to new trading partners. The contract parties cannot switch without costs if they have made ex-ante relationship-specific investments. • B may have made investments in machinery that is customized to the equipment delivered by A • A may have made investments in knowledge about the production process that is specific to the requirements of B. Economics of the firm – Tore Nilssen – Lecture 1: Theory of the firm – page 10 The ex-ante costs of renegotiation: If such investments in the relationship cause problems for you later on, when revision of the contract is necessary, you may want to invest less than what is socially optimum. • Because of the risk of renegotiation later on, A and B use machinery and knowledge that are more general-purpose than what would be profitable for them if a complete contract could be written. • If B’s machinery can only be used together with equipment from A, then B’s bargaining position during renegotiations is weak. B does not want this to happen. This is called the hold-up problem. Summary so far: • incomplete contracts • relationship-specific contracts → the hold-up problem Economics of the firm – Tore Nilssen – Lecture 1: Theory of the firm – page 11 To integrate or not to integrate – that is the question Should A and B continue as two separate firms, or should they integrate into one firm? If they continue as separate firms: • the hold-up problem • transaction costs The alternative: Integration But:Who is the owner of the integrated firm? What does it mean to be owner? Authority: The right to make decisions when something occurs that is not written into the contract. Economics of the firm – Tore Nilssen – Lecture 1: Theory of the firm – page 12 The property-rights approach: A and B have three options: • continue separately • integrate with A the owner • integrate with B the owner For example: B being owner of the firm A+B is • good for B, and • bad for A, relative to non-integration. • A looses the right to renegotiate. When the initial contract is written, they make the integration decision. The arrangement that maximizes their combined expected profits is chosen. • The transaction-cost theory emphasizes the costs of nonintegration. • The property-rights approach emphasizes that there are also costs of integration [for the non-owner(s)]. Integration occurs when its benefits exceed its costs, relative to non-integration. Economics of the firm – Tore Nilssen – Lecture 1: Theory of the firm – page 13