IDA’s Performance Based Allocation System: IDA16

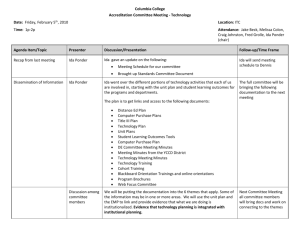

advertisement