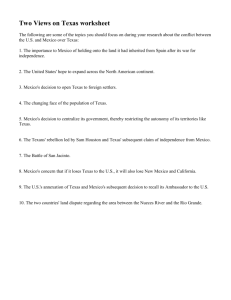

Water Management in the Binational Texas/Mexico Río Grande/Río Bravo Basin

advertisement