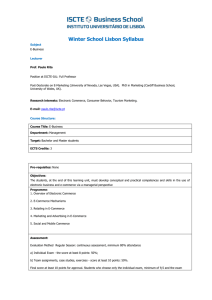

Economics and Electronic Commerce: Survey and Directions for Research

advertisement