Environment for Development User Financing in a National Payments for Environmental Services

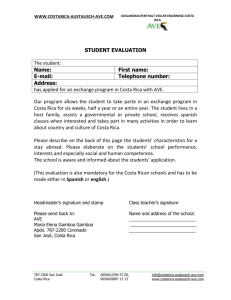

advertisement