R E V I E W S

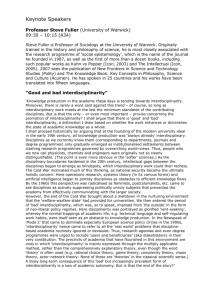

advertisement