SCC landmark decisions

outline path forward for

Ontario mining industry

By Melanie Franner

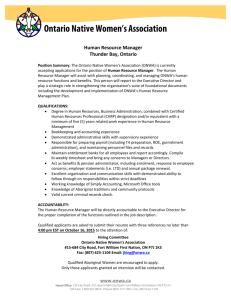

Brian Dominique, partner, Cassels Brock & Blackwell LLP.

Linda Knol, partner, Cassels Brock & Blackwell LLP.

Two recent rulings by the Supreme Court

of Canada (SCC) have brought to the fore

the issue of Canadian Aboriginal land title

and treaty harvesting rights. The first case

(Tsilhqot’in Nation v. British Columbia) saw

the SCC rule in favour of Aboriginal title

to over 1,750 kilometres of land in British

Columbia to the Tsilhqot’in Nation. Fifteen

days later, on July 11, 2014, the SCC ruled

in the second case (Grassy Narrows First

Nation v. Ontario) that the Government of

Ontario has the authority to “take up” land

in the Keewatin Territory (which is located

in northwestern Ontario) under the terms

of Treaty 3.

Although the two rulings may at initial

glance seem at odds with each other, both

have helped to define how future Aboriginal

land and treaty rights will be established and/

or interpreted in Canada. And both have produced precedent-setting decisions that will

be felt by industry for many years to come.

New Law in the Making

“There is no question that these two

recent SCC rulings are significant,” states

Brian Dominique, partner, Cassels Brock &

Blackwell LLP, the law firm that represented

Goldcorp Inc. at the Court of Appeal for

Ontario and the SCC in the Grassy Narrows case. “Each is significant for its own

reasons.”

In the B.C. Tsilhqot’in case, the SCC ruling recognized and made a finding of Aboriginal title to lands in Canada for the very

first time. It did so on lands in which there

was no existing land treaty in place. In making its ruling, the SCC clarified the legal test

for the establishment of Aboriginal title,

namely that the First Nation asserting title

must establish: sufficient pre-sovereignty

occupation; continuous occupation; and

exclusive historic occupation. If Aboriginal title is established, then the Aboriginal

titleholders have the right to decide how the

land will be used and to the benefits of such

use.

But also significant is the fact that the

SCC ruled in favour of provincial constitutional authority to infringe Aboriginal title

Fall 2014

5

and treaty harvesting rights if the infringement can be justified. This ruling reversed

previous case law that had recognized that

right solely to the federal government.

“The test for determining if a province

can infringe upon Aboriginal title or treaty

harvesting rights requires the government

to demonstrate a compelling and substantial objective and that its actions are consistent with the fiduciary duty it owes to the

affected First Nations,” explains Linda Knol,

partner, Cassels Brock & Blackwell LLP.

6

Ontario Mineral Exploration Review

“Proof that the government’s actions are

consistent with its fiduciary duties involves

the following considerations: the infringement must be necessary to achieve the government’s objectives, the government must

go no further than necessary to achieve its

objectives, and the benefits must not outweigh the adverse affects on the Aboriginal

interest.”

The government’s infringement can be

justified, in principle, for the development

of agriculture, forestry, mining, hydroelec-

tric power, general economic development,

protection of the environment or endangered species, the building of infrastructure,

and the settlement of foreign populations to

support these objectives.

Infringement or

Adverse Effects

Between the two decisions, the SCC has

outlined how the government is to address

Aboriginal title and treaty harvesting rights

under various scenarios, including cases

where Aboriginal title has been established,

cases where Aboriginal title has been asserted but not yet established, and cases where

the First Nation has surrendered title under

a treaty but has retained the right to harvest

over any surrendered land not taken up by

the Crown.

In each of these scenarios, the common

factor is the duty of the Crown to consult

with and potentially accommodate any First

Nation whose interests may be affected by a

proposed project or the taking up of land.

These “good faith” consultations are mandatory.

In cases where Aboriginal title has been

established, any taking up of land (by, for

example, granting a mining lease or approving a gas pipeline) without the consent of

the Aboriginal titleholder will constitute an

infringement of the Aboriginal titleholder’s

rights that must be justified by the Crown.

What isn’t quite as concrete is the definition of “infringement” in the context of

treaty harvesting rights.

Knol notes that in the Grassy Narrows

ruling, the SCC confirmed its 2005 decision in Mikisew Cree First Nation v. Canada

that the Crown’s authority to take up treaty

lands is not unconditional.

“Ontario has the duty to consult with

First Nations and to accommodate their

interests where appropriate, and Ontario

cannot take up so much surrendered treaty

land that the First Nation’s right to harvest in their traditional territories becomes

meaningless,” she states. “However, the test

that the courts will apply to determine the

point at which a treaty harvesting right becomes meaningless is still unclear.”

Dominique notes that the rulings by the

SCC are already being interpreted by interested parties in different ways. “I think

we’ll see at least another 20 years of litiga-

tion on the issue of infringement before a

happened if the SCC didn’t find in favour

full framework of basic principals are estab-

of Ontario in order to understand the sig-

lished,” he says. “The Aboriginal side is likely

nificance of the decision,” says Knol. “If the

to approach the requirements of consulta-

SCC had ruled the other way, then all of the

tion as having to meet the higher standard

land-use decisions that Ontario made over

of infringement in all instances, rather than

the last 100 years in the Keewatin Territo-

the standard required to be met for an ad-

ry, such as the grant or issuance of mining

verse affect.”

leases and forestry licences and other interests in land, would have been called into

Canada versus Ontario

question as it would have been uncertain if

The Grassy Narrows decision was significant for a couple of other important

Ontario had the authority to grant or issue

them.”

reasons. For one, it put to bed the question

Had the SCC ruled against Ontario in

of whether Canada alone is responsible for

this case, it would also have set a precedent

fulfilling the Treaty 3 promises. Canada was

for other treaties and other provincial gov-

the Crown signatory to the treaty, which

ernments.

was signed in 1873, but it subsequently an-

“Had the ruling gone the other way, not

nexed that land to Ontario. The SCC ruled

only would Treaty 3 have to be re-written, in

that, as Crown representatives, both Canada

essence, but it would put into question the

and Ontario are responsible for fulfilling

terms of several of the other land treaties

the Treaty 3 promises within their respec-

across the country,” adds Dominique.

tive spheres of jurisdiction.

“In the Grassy Narrows SCC ruling, I

think one has to look at what would have

Moving Forward

Although the two recent SCC decisions

have gone a long way in defining Aboriginal

land title and treaty rights, they have also

opened the door to further interpretation

that will more than likely require additional

court cases, appeals and potentially, SCC

rulings.

As to how industry will deal with these

issues, only time will tell. Until then, the status quo remains.

“The fact that Ontario is substantially a

treaty province is an obvious benefit,” states

Dominique. “There may be some uncertainties in the future, but on a day-by-day

basis, it’s kind of business as usual for industry. Ontario mining companies, for the

most part, understand the need to consult

with and accommodate the interests of First

Nations in good faith. They’ve been doing

that already. At some point, however, the

parties are going to come to loggerheads

about how to determine the distinction between impairment and infringement. But

until then, it’s business as usual, as industry

and Aboriginal peoples have come to know

it.”

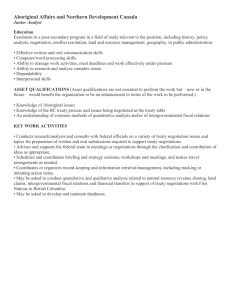

We dig mining.

”Dirt Law.” Those two words cover

a lot of ground – claims, permits,

treaty negotiations, development

deals, working with vendors, with

governments, you name it. It’s the

law of day-to-day mine operations.

To make sure it’s done right, here

are two more words: Cassels Brock.

casselsbrock.com/mining

© 2014 Cassels Brock. All rights reserved.

Cassels Brock - December 2, 2014

Ontario Mineral Exploration Review Magazine

Half page horizontal - 7” x 4.625”

Submitted by: Heather Murray

hmurray@casselsbrock.com

416 869 5782 - fax 416 642 7137

Falleither

2014

Please PRINT a hard copy of the file and

FAX it or SCAN and EMAIL it back to me,

thanks!

7