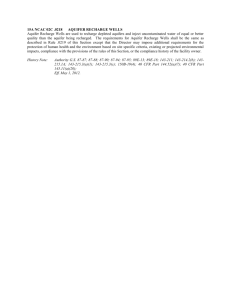

Institute of Government A Report to the Georgia Environmental Protection Division Athens, Georgia

advertisement