F E S :

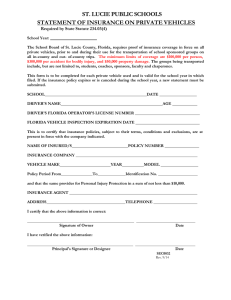

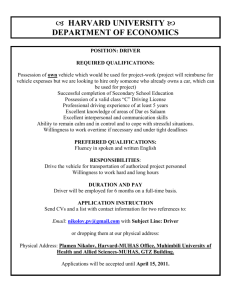

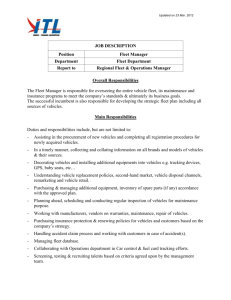

advertisement