26 Chapter Seed Germination Kent R. Jorgensen

Kent R. Jorgensen

G. Richard Wilson

Chapter

26

Seed Germination

Seed germination represents the means for survival and spread of many plants (McDonough 1977). Germination consists of three overlapping processes: (1) absorption of water, mainly by imbibition, causing swelling of the seed; (2) concurrent enzymatic activity and increased respiration and assimilation rates; and (3) cell enlargement and divisions resulting in emergence of root and plumule (Evanari 1957; Schopmeyer

1974b).

Germination is most commonly expressed as germination capacity, which is the percentage of seed that germinates during a period of time that ends when essentially all germinable seed have germinated. Germination energy is sometimes used in the literature. Germination energy is the percentage of seed that germinates during a specific time interval that is determined by the peak of germination. Germination capacity and germination energy will generally vary considerably within a seed lot (table 1).

USDA Forest Service Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-136. 2004 723

Chapter 26 Seed Germination

Table 1—Mean germination energy and mean germination capacity of 18 grass, 27 forb, and 28 shrub species following specified number of days. Germinated in the dark at 34 to 38

∞

F (1.1 to 3.3

∞

C).

Species

Germinative energy a

Percent Days

Germinative capacity

Percent b

Days

Number of accessions c

Grasses

Bluegrass, Kentucky

Brome, mountain

Brome, meadow, ‘Regar’

Brome, smooth southern

Fescue, hard sheep

Foxtail, meadow

Orchardgrass

Orchardgrass, ‘Paiute’

Rye, mountain

Squirreltail, bottlebrush

Wheatgrass, bluebunch

Wheatgrass, standard crested

Wheatgrass, fairway crested

‘Ephraim’

Wheatgrass, intermediate

Wheatgrass, pubescent ‘Luna’

Wheatgrass, tall

Wildrye, Great Basin ‘Magnar’

Wildrye, Russian

Forbs

Alfalfa ‘Ladak’

Alfalfa ‘Nomad’

Aster, Pacific

Aster, Engelmann

Aster, blueleaf

Balsamroot, arrowleaf

Balsamroot, cutleaf

Burnet, small

Clover, strawberry

Cowparsnip

Crownvetch

Flax, Lewis ‘Appar’

Geranium, Richardson

Goldeneye, showy

Helianthella, oneflower

Lomatium, narrowleaf

Lupine, mountain

Lupine, silky

Milkvetch, cicer

Penstemon, low

Penstemon, Palmer ‘Cedar’

Sainfoin

Salsify, vegetable oyster

Sweetanise

Sweetvetch, Utah (shelled)

Sweetvetch, Utah (unshelled)

Sweetclover, yellow

Shrubs

Apache plume

Bitterbrush, antelope

Bitterbrush, desert

Ceanothus, Martin e

Chokecherry, black

27

54

90

67

58

75

70

30

45

75

85

78

90

70

70

75

53

70

85

56

34

80

26

26

17

80

56

30

35

70

16

20

50

49

63

73

20

21

62

80

48

34

40

28

75

23

72

58

33

32

70

38

28

21

30

30

28

56

30

28

21

30

28

28

28

30

50

28

14

14

120

150

90

98

98

21

60

150

45

45

180

150

90

130

36

56

75

150

49

21

35

180

50

50

14

60

42

28

120

150

30

77

92

80

82

80

91

72

49

95

93

88

92

93

93

90

75

91

92(3) d

94(3) d

59

83

48

40

35

91

91

64

55(20) d

80

22

27

90

72

77

95

32(65) d

42

86

91

63

60

63

34

90

63

90

86

38

72

365

120

42

49

60

75

45

112

60

49

45

80

42

50

50

120

250

49

28

45

180

180

180

175

180

35

365

365

180

75

365

365

180

365

98

98

150

365

63

35

130

365

200

210

42

180

56

70

240

365

16

5

8

8

8

30

12

12

8

7

6

7

6

24

10

10

18

12

8

40

12

8

8

10

10

8

8

16

10

18

4

20

10

22

10

8

4

7

12

22

4

6

4

12

10

16

30

16

8

4

(con.)

724 USDA Forest Service Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-136. 2004

Chapter 26 Seed Germination

Table 1 (Con.)

Species

Germinative energy a

Percent Days

Germinative capacity b

Percent Days

Number of accessions c

Shrubs

Cliffrose

Currant, golden

Ephedra, green

Ephedra, Nevada

Greasewood, black e

Hopsage, spiny

Kochia, forage ‘Immigrant’

Mountain mahogany, curlleaf

Mountain mahogany, true

Peachbrush, desert

Rabbitbrush, mountain low

Rabbitbrush, mountain rubber

Rabbitbrush, whitestem rubber

Sagebrush, basin big

Sagebrush, black

Sagebrush, fringed

Sagebrush, mountain big

Sagebrush, Wyoming big

Saltbush, fourwing e

Saltbush, Gardner e

Serviceberry, Saskatoon

Serviceberry, Utah

Winterfat

70

37

74

80

30

60

60

53

64

57

63

55

60

60

59

15

45

38

26

16

63

77

55

70

90

56

21

45

40

35

105

63

45

180

49

42

63

42

74

48

48

42

90

330

104

14

84

70

91

93

46

82

87

68

83

75

73

72

70

61

75

36

82

76

39

24

80

94

84

91

365

70

35

180

120

49

365

112

180

365

63

56

70

91

365

104

104

63

180

365

210

28 a

Percentage of seed that germinate during a specific time interval that is determined by the peak of germination.

b

Percentage of seed that germinate during a period of time ending when essentially all germatable seed have germinated.

c

Number of accessions used in determining results. Two 100 seed samples per accession were evaluated.

d

Percent hard seed in parenthesis.

e

Fifty percent fill, all other species 95 to 100 percent fill.

22

36

14

4

20

8

6

8

4

18

30

16

18

7

18

12

32

12

60

8

12

10

24

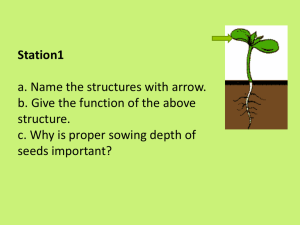

A mature, viable nondormant seed (fig. 1) will germinate (fig. 2) if placed under favorable conditions of moisture, temperature, gas exchange, and light (for some species). There is an interdependence between these factors as well as between age of seed and storage conditions. The conditions that allow germination to occur and the time required for germination can vary dramatically between seed lots of a species (Meyer and Monsen 1990; Meyer and

Pendleton 1990; Meyer and others 1987, 1989; Stevens and Jorgensen 1994; Young and others 1984d).

Figure 1—Mature, viable antelope bitterbrush seed.

USDA Forest Service Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-136. 2004

Figure 2—Germinating antelope bitterbrush seed.

725

Chapter 26

Moisture _______________________

The cells of the germinating seed cannot carry on the vital process of germination without sufficient water. The rate of water absorption is largely dependent upon the degree of seedcoat permeability and availability of water. Seedcoat permeability and rate of water uptake can be increased in some species by mechanical, chemical, or hot water treatments (see chapter 24). Seeds of some species will absorb the amount of water required for germination in a short period; others take a much longer period. Rubber rabbitbrush will absorb the amount of water required for germination in about 36 hours, whereas seed of blue elderberry requires a much longer period: 180 days or more.

Too much water can be harmful to some seeds. Most can be soaked in water for 3 to 5 days without decreasing germination, but care should be taken if seed is soaked for longer periods.

Temperature ____________________

Seeds of many species can germinate over a wide range of temperatures. Others germinate only within narrow temperature ranges (Schopmeyer 1974b). Seed of several plant species have the capacity to germinate at temperatures close to 32

∞

F (0

∞

C). Right after snow melt, soil temperatures are generally low and soil water levels are high. Under these conditions, those seeds that germinate at low temperatures have a good chance for survival, with adequate moisture being available for continued growth.

Knowing the temperature or combination of temperatures at which a species will exhibit maximum germination can help in determining the most ideal time to sow the seed. Optimum germination temperatures have been determined for a number of shrubs (Allen and others 1986a,c, 1987; Dettori and others 1984; Evans and Young 1977a; Springfield

1972a; Young and others 1981a; Young and Evans

1981b), cool season grasses (Allen and others 1986b;

Young and Evans 1978a, 1981a, 1982, 1984; Young and others 1981a), and forbs (Allen and Davis 1986;

Allen and others 1986b; Young and Evans 1979).

Extreme high temperature, such as in a fire can increase germination and emergence of species like buckbrush, smooth sumac, and lodgepole pine. Rupture of the seedcoat structure and heat inactivation of inhibitors are possible explanations for the effect fire has on seed germination (McDonough 1977).

Gas Exchange __________________

Most seeds will not germinate when the soil is too wet, when seeds are planted too deep, or when conditions limit the supply of oxygen. Oxygen has to be present for germination to take place. A low rate of

726

Seed Germination oxygen uptake permits only the earliest stages of germination to occur. If a continual source of oxygen is not available, germination will stop and the seed will die. Oxygen is also essential for normal seedling development. Oxygen requirements can affect seeding time, seeding depth, and selection of areas to seed.

The rate of oxygen absorption during seed germination and seedling development is highly variable among species (Schopmeyer 1974b).

Light __________________________

Under natural conditions, some seeds become buried and germinate without light. However, light is essential for seed germination of many species. Depth of seeding should be controlled as well as possible when sowing seeds of species having a light requirement (Schopmeyer 1974b). Indian ricegrass, western wheatgrass, and Great Basin wildrye are a few species that germinate best in the dark (seed covered).

Mountain brome, slender wheatgrass, blue grama, big sagebrush, and forage kochia are species that require light to germinate.

Afterripening ___________________

Another factor encountered in the germination process is afterripening or a continuation of the maturing process after harvest. There are a number of grasses, forbs, and shrubs that exhibit afterripening

(Stevens and Jorgensen 1994) (table 2; also see chapter 24). Seed that has been collected before fully ripening, or seed freshly harvested can, initially, exhibit low germination that will increase after a period of air-dry storage. This process hardens the embryo, and in some instances helps increase the ability of the seed to absorb the water needed for the germination process. Whether or not afterripening occurs depends upon a number of factors, including site differences, degree of seed maturity at harvest, conditions of storage, and ecotypic differences within species (McDonough 1977).

Dormancy ______________________

Viable and uninjured seeds of most shrub species will not germinate without seed dormancy being broken or overcome. The degree of seed dormancy varies between species (fig. 3; table 2; also see chapter 24).

For example, forage kochia and winterfat only require afterripening, whereas, wildrose and blue elderberry require 1 or 2 years or cold moist stratification to break dormancy. Most grasses exhibit little dormancy.

An exception is Indian ricegrass (Young and Evans

1984), which exhibits a profoundly dormant embryo.

Seed of most forb species, with the exception of the legumes, posses a moderate level of dormancy. Many

USDA Forest Service Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-136. 2004

Chapter 26 Seed Germination

Table 2—Mean percent germination of seed from 39 plant species after 2 to 25 years of storage in an open warehouse (Stevens and Jorgensen 1994).

Species Source 2 3 4 5

Years of storage

7 10 15 20 25

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Percent germination a,b,c,d

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Grasses

Intermediate wheatgrass

Smooth brome

Winter rye

Forbs

Alfalfa

Washington

Colorado

Idaho

95

70

89

96

71–

88

93

52

82

94

39–

75–

80

15

56

78–

11

48

63

3

32–

13

1

2

Balsamroot, arrowleaf

Balsamroot, cutleaf

Burnet, small

Cowparsnip

Eriogonum, Wyeth

Flax, Lewis

Globemallow, gooseberry

Goldeneye, showy

Ligusticum, Porter

Lomatium, Nuttall

Lupine, mountain

Lupine, silky

Penstemon, Palmer

Salsify, vegetable-oyster

Sweetvetch, Utah

Canada same + hard seed

Paradise Valley, NV

Bountiful, UT

Ephraim, UT

Pleasant Cr. Canyon, UT

Brigham City, UT

Ephraim, UT

Benmore, UT

Ephraim Canyon, UT

Ephraim Canyon, UT

Ephraim Canyon, UT

Ephraim Canyon, UT

Ephraim Canyon, UT

Ephraim Canyon, UT

Mt. Pleasant, UT

Orem, UT

69

58

97

83

66*

7

18

41

65

59

69

92

40

76

95

42

35 28–

88*+ 93

7 8–

51*+ 87

75

94

17

91

2

73

77

99

81

72*+ 85

7 6

17

28

11

24

65

67

69

100

66

58

93

9

13

36–

73–

60–

99–

79–

66–

55–

75

92

37–

20–

96–

1

90–

83

6

13–

13

37–

26

86

65

46

25

70

79

20

4

82

0

64–

8

28

85

50

70–

7

1

0

31–

40

77

86–

1

0

87

0

16–

66

71

0

0

88–

0

5

25

6

0

0

2

13

92–

13

16

Shrubs

Bitterbrush, antelope

Bitterbrush, desert

Ceanothus, Martin

Cliffrose

Currant, golden

Ephedra, green

Ephedra, Nevada

Hopsage, spineless

Mt. Dell, UT

Bishop, CA

Manti Canyon, UT

American Fork, UT

Manti, UT

Manti, UT

Wah-Wah Valley, UT

Escalante, UT

Indian apple Ephraim Canyon, UT

Mountain mahogany, curlleaf Mayfield, UT

Mountain mahogany, true

Rabbitbrush, whitestem

rubber

Sagebrush, basin big

Ephraim Canyon, UT

Richfield, UT

Sagebrush, black

Saltbush, fourwing

Serviceberry, Saskatoon

Serviceberry, Utah

Snowberry, mountain

Winterfat

Ephraim, UT

Manti, UT

Panaca, NV

Spring City Canyon, UT

Henrieville, UT

91

97

Spanish Fork Canyon, UT 80

Corona, NM 90

48

88

90

87

79*+ 86

78 86

3 5

80*+ 89

92

93

92

42

67

63

80–

73

81–

32

42

63

65

65–

82

66

47

80

99

64

83

87

80

5

–

92

91

86–

42

61

34–

67

55–

40

94

80

12

89

28

84

85

57–

37

80

68–

14

70–

34–

40

91

99

92

18

88

69

10+

84

80

89

13

39–

76

46–

11–

24–

5

50

85–

96

80–

7

88

73

40

89

27–

82

91

6

21

69

25–

7

1

1

43

72

90–

44–

0

85

65

36–

91–

6

88–

85–

0

10–

64–

3

0

0

0

37–

76–

67–

8

0

84–

61

5

66

2

24

79

0

–

44

0

0

0

0

18

10

0

1

5

74– a

Results based on four samples of 100 seeds each at 98 percent or better fill and 100 percent purity, except fill for fourwing saltbush (52 percent fill) and Martin ceanothus (59 percent fill).

b

Asterisk (*) indicates significant afterripening.

c

Plus sign (+) indicates significant increase in germination between adjoining years at the 0.5 level.

d

Minus sign (–) indicates significant decrease in germination between adjoining years at the 0.5 level.

0

0

11

0.3

0

8

0

77

0

0

2

74

60

6

63

0

28

0

0

75

–

0

6

0

11

0

0

8

–

73

78

0

0

69+

0

–

76

0

0

1

0

21

0

0

0

2

67

71

0

0

83

0

0

1

0

0

USDA Forest Service Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-136. 2004 727

Chapter 26

A C

Seed Germination

B D

Figure 3—Mean germination over time of multiple accessions (number of accessions listed in parenthesis following common name) of selected grasses, forbs, and shrubs in the dark at 34 to 38

∞

F (1.0 to

3.3

∞

C). Two samples of 100 seeds each examined for each accession.

A. Bluebunch wheatgrass (8), fairway crested wheatgrass (8), meadow brome, ‘Regar’ (6), intermediate wheatgrass (24), and pubescent wheatgrass (10).

B. Orchardgrass (7), and orchardgrass, ‘Paiute’ (16).

C. Great Basin wildrye (18) and Russian wildrye (12).

D. Bottlebrush squirreltail (8), smooth brome (6), and hard sheep fescue (12).

E. Cicer milkvetch (18), arrowleaf balsamroot (8), and blueleaf aster (8).

F. Utah sweetvetch with seed out of loment (10), and Utah sweetvetch with seed in loment (20).

G. Yellow sweetclover (22), Palmer penstemon (10), and Lewis flax (32).

H. ‘Ladak’ alfalfa (30) and small burnet (10).

I. Nineleaf lomatium (8) and sweetanise (8).

J. Mountain lupine (16) and silky lupine (10).

K. Wyoming big sagebrush (12), basin big sagebrush (36), mountain big sagebrush (32), and black sagebrush (14).

L. Antelope bitterbrush (40) and cliffrose (18).

M. Winterfat (24), forage kochia (30), and fourwing saltbush (61).

N. Whitestem rubber rabbitbrush (22), green ephedra (18), and true mountain mahogany (20).

O. Curlleaf mountain mahogany (16) and black chokecherry (8).

728 USDA Forest Service Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-136. 2004

Chapter 26

Figure 3 (Con.)

E

F I

H

Seed Germination

G

USDA Forest Service Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-136. 2004

J

729

Chapter 26

Figure 3 (Con.)

K

L

N

Seed Germination

O

730

M shrubs exhibit considerable seed dormancy. Time required for germination to occur varies between species and among accessions within a species (tables 1,

2, and 3; fig. 3) (Meyer and Monsen 1990; Meyer and others 1987, 1989; Stevens and Jorgensen 1994). Species that require more than 4 weeks to germinate should be fall-seeded to allow the seed sufficient time to overcome seed dormancy. This will also ensure that germination occurs at a time when the seedling can take full advantage of available seasonal soil moisture. Species exhibiting little dormancy can be springseeded if the date of seeding allows sufficient time for germination and seedling establishment prior to the usual soil drying experienced as the growing season progresses.

USDA Forest Service Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-136. 2004

Chapter 26

Longevity ______________________

The life span of seeds is affected by many variables such as: (1) the inherent nature of individual plant species; (2) condition of seed at harvest; (3) cleaning techniques; (4) storage conditions; (5) age of seed;

(6) degree of infestation by disease organisms and insects; and (7) exposure to harmful chemicals. Fluctuating seed moisture content and high temperatures are especially damaging to seed longevity. Storing dried seed at low temperatures in vapor-tight containers will preserve seed viability for extended periods of time. Seed of forage kochia, dried to a 7 percent moisture content, and stored at room temperatures in airtight containers, have exhibited over 90 percent germination after 3 years. Undried seed stored at

Seed Germination room temperature had only 14 percent germination after 3 years (Jorgensen and Davis 1984). In general, seed with hard coats and low water content are longerlived, while seed with either relatively high water content, soft seedcoats, or both are shorter-lived

(Quick 1961). There are exceptions to this generalization. Stevens and Jorgensen (1994) have reported on the longevity of many commonly used Intermountain species (tables 2, 3).

Location and Year of Production ___

Most species have a wide range of distribution, some larger than others. Populations of the same species growing under different climatic and edaphic conditions can exhibit different germination requirements.

Table 3—Percent germination of the same seed lots for grass, forb, and shrub seed the year of collection and following various years of storage in an open warehouse (Stevens and Jorgensen 1994).

Common names 0 5 6 7 8

Years of storage

9 10 11 12 13 14 15

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Percent germination a,b,c,d,e

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Grasses

Brome, smooth

Fescue, meadow

Needle-and-thread

Ricegrass, Indian

Ricegrass, Indian

Spike muhly

Wheatgrass, tall

Wheatgrass, tall

Wheatgrass, tall

Forbs

Astragalus, giant

Crownvetch

Goldeneye, showy

Goldeneye, showy

Goldeneye, showy

Milkvetch, cicer

Milkvetch, cicer

Penstemon, Eaton

Penstemon, Eaton

Penstemon, Palmer

Penstemon, thickleaf

Sweetanise

91

69*

88

55

9*

14*

72*

85

85

88

41*

44

30*

39

73

51*

63*

71*

89

74

94

94

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

+

–

0

+

+

+

0

0

0

+

+

–

0

+

–

0

0

+

+

–

0

0

63

0

0

62

0

0

0

89

0

0

0

89

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

99

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

70

0

65

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

91

87

92

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

63

0

0

0

0

0

75

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

Shrubs

Buffaloberry, silver

Honeysuckle

Indian apple

Indian apple

Oregon grape

Peashrub, Siberian

85

57

67

58

25

88

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

–

–

0

0

85

0

0

0

58

0

0

0

0

49

0

0

0

88

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0 a

Results based on two samples of 100 seeds, each at 100 percent purity.

b

Asterisk (*) indicates significant afterripening.

c

Plus sign (+) indicates significant increase in germination between germination years at the 0.05 level.

d

Minus sign (–) indicates significant decrease in germination between germination years at the 0.05 level.

e

Zero (0) indicates no data.

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

31

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

82

87

82

0

44

0

23

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

68

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

49

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

1

0

0

0

0

0

USDA Forest Service Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-136. 2004 731

Chapter 26

In work with rubber rabbitbrush, big sagebrush, and hopsage, clear relationships between collection site climate and seed germination patterns have been found (Meyer and Monsen 1990; Meyer and Pendleton

1990; Meyer and others 1987, 1989). Seed source should, therefore, be considered when purchasing seed. Seed from sources similar to that of the proposed planting site should be given preference over sources from locations having significantly different environmental conditions.

Seed Germination

Often, germination percentage of a species from the same site will vary between years. Generally, percent germination is higher during years of high seed production than in years of poor seed production. Antelope bitterbrush collected in central Utah during high production years usually exhibits 95 percent or more germination, but during years of poor seed production the germination has varied from a low of 8 percent to a high of 68 percent.

732 USDA Forest Service Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-136. 2004