1 Preface

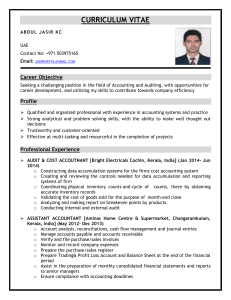

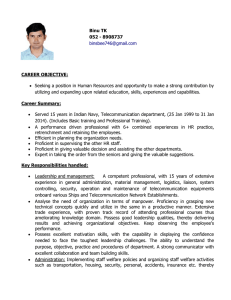

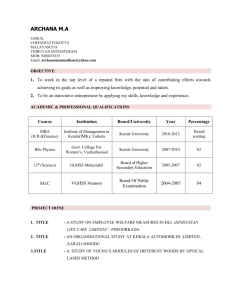

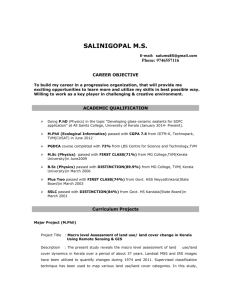

advertisement