Document 11353139

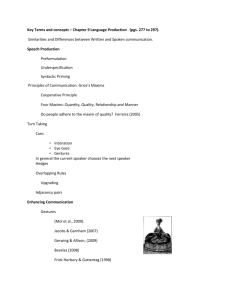

advertisement