Document 11300575

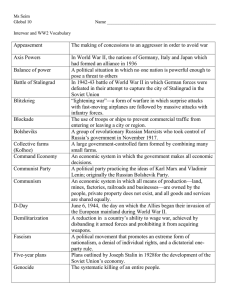

advertisement