1 by (1981) B.A., Boston University

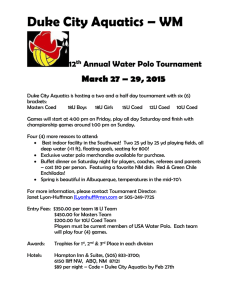

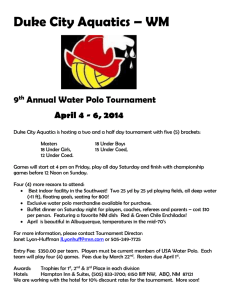

advertisement