Document 11282627

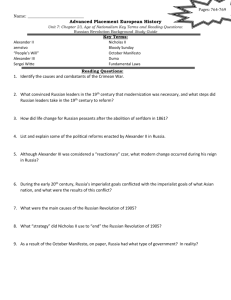

advertisement