LINKING ENVIRONMENTAL POLICY DEVELOPMENT: Susan Miriam Minter

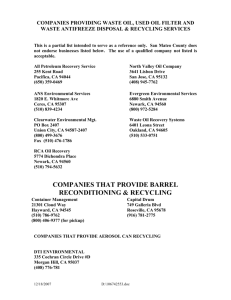

advertisement