JUN 3 0 LIBRARIES

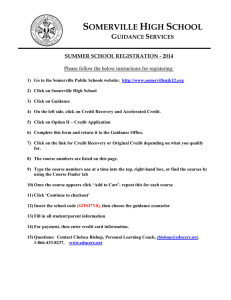

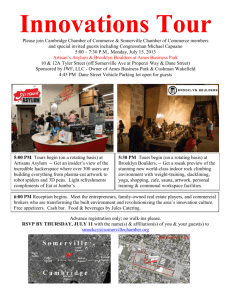

advertisement