No Room to Breathe

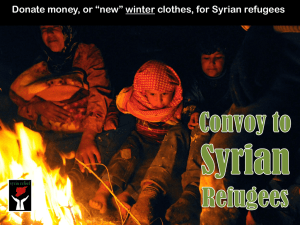

advertisement