GAO MARITIME SECURITY Vessel Tracking Systems Provide Key

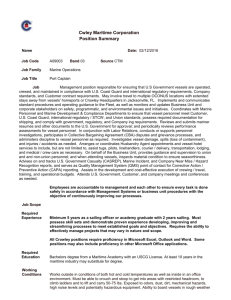

advertisement