MARITIME SECURITY DHS Could Benefit from Tracking Progress in

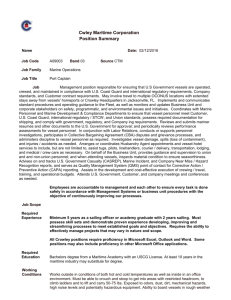

advertisement