GAO INFLUENZA VACCINE Federal Investments

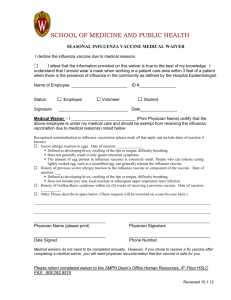

advertisement