GAO HOMELAND SECURITY Federal Protective

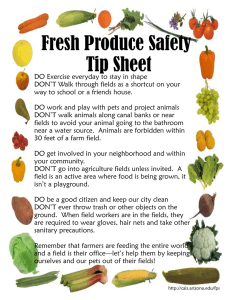

advertisement