GAO HOMELAND SECURITY Greater Attention to

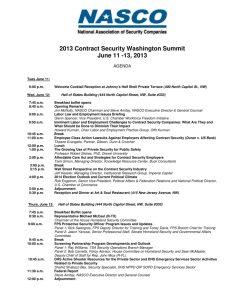

advertisement