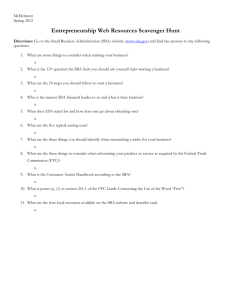

GAO SMALL BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION Response to

advertisement